Do you know the old saying, “Be open-minded, but not so much your brains fall out”? Though the skeptics who tout this quip might not be super-friendly toward the religious in general and Pagans in particular, there’s a certain amount of truth to the saying when it comes to defining Paganism itself.

Over the past years, in an attempt to be inclusive, the definition of Pagan has been broadened time and time again. To a certain extent, this is reasonable; some of this redefinition reflects growth and innovation in our community. Paganism is relatively new and still developing, and the definition needs to change with our understanding.

But there is a separate problem with this constant redefinition of Paganism. We mostly have come to rely on an operational definition of Paganism. It is commonly argued that “Pagan” is whatever people we recognize as Pagans say it is.

At that point, we have to admit that this definition of “Pagan” is no longer theoretical, it is simply a social construct. On the face of it, that is technically true of every word and symbol. However, this is a rhetorical position and not a productive one. (1)

When we decide that “Pagan” is a socially-defined grouping rather than a religious one, we quickly reach the point that, as Jason Mankey explores here, the term Pagan itself becomes “inadequate” – though I would go further to say irrelevant – as a means of describing our spiritual and religious activity.

Revitalization Movement

It sometimes seems Paganism has gone from being a revitalization movement (2) to a social movement. When we reach the point where Pagan membership is simply through self-ascription – “I’m Pagan and you can’t tell me I’m not!” – we’ve lost something important.

As a reaction to that trend of defining Pagan socially, I have developed a theoretical definition of “Pagan” religion that will allow me to at least think clearly about what is Pagan, and what is not.

While formally studying anthropology of religion, I examined the social structures that exist around religion. As scientific research, my observations were necessarily divorced from any discussion of actual religious experiences. That is, statements about religious experience were considered to be “social facts” and not examined spiritually, but only socially.

As to whether the religious practitioners were describing something real, imaginary, or in between, it was necessary for me to remain intentionally and willfully agnostic. Anthropology is science, and while we can observe and describe the social structures around religious experience, science cannot delve into those actual experiences in any effective manner. There is a gentleman’s agreement not to try.

My role now has changed; as a member of the Pagan community, I have a different seat from which to observe. As a group member, I am privy to insider views, have access to different kinds of evidence, and an welcome in different (and deeper) conversations.

From this very specific perspective, I have attempted to form a definition of Paganism that is an honest reflection on Pagan experience. Such a definition, while not scientifically admissible, is at least informed by the academy.

Read more at http://admin.patheos.com/blogs/agora/?p=16234#yr8dhRTk7u2oM0LG.99

Religion Defined

The first boundary we need is to define religion. A religion is a cultural structure that regulates interaction with the spiritual and sacred other.(3) This is slightly different from the definition that you might find in a textbook. Here we admit that there is an actual ‘other’ to contact. I think we can take it a bit further and say that we are so constantly in contact with it that we need tools to manage relations.

This defines religion pretty broad. Through this lens, Christianity is a religion, but so is the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. Spiritualism would be a religion, and so would Shinto.

This definition lacks many of the standard Western hallmarks of religion. It lacks specific reference to deities, dodges explanatory functions (4),ignores the creation of the universe, and ditches the metaphysical underpinnings of the social order. While these things can and do exist in religions, I believe it is key to realize that they are not the point of religion.

By common Western understandings of religion, the spiritual and sacred “other” is strictly defined. This makes sense when we realize that the purpose of religion is to put a name and face on something that is otherwise beyond description. It is through what we call religion that we extend ourselves from the everyday world to reach for something out there.

With that behind us, let’s see if we can get to describing what Paganism is.

Paganism Is Western

In the Judeo-Christian tradition, everything is understood in a relation to a single deity. They have texts that define and shape those relationships. When questions arise, it is to sacred texts, their commentaries, and the long history that members turn. Experiences outside of that framework are at best considered dangerous.

Because of the Judeo-Christian influence on Western thought, we have long attempted to understand other religions (and the religious “other”) through this same lens. We ask, what do they believe? who are their gods? who told them these things?

However, both Paganism and the New Age are variations from (or rebellions against) these Western norms. Neither gives strict definitions of the spiritual or sacred “other.” They are more a collection of sects and loose beliefs, a collection of practices and a broad field of experiences.

For Paganism and the New Age (I’ll differentiate them later), the first part of the definition is simple: they are Western. Paganism and the New Age are both Western religious phenomena. Non-Western religions are not part of the New Age or Paganism.

Non-Western practices studied under traditional authority and practiced within their original context simply are what they are. When they inform New Age or Pagan thought, they are being incorporated into something wholly different.

No matter how similar to a Pagan or New Age belief a non-Western practice is, it is neither part of the the New Age nor Paganism by the simple fact that it is not Western in origin or by tradition. For example, an American Shintoist is not a Pagan (5), but a Japanese Wiccan would be.

Pagans Are Not Judeo-Christians

The second part of the definition of Pagan is where we have to define what it is not. Paganism is not part of the Judeo-Christian tradition. Paganism might at times be shaped by Christianity and informed by its history, but that same truth can be said of just about every aspect of Western culture. (6)

While I understand John Beckett’s proposition that it is rhetorically problematic to define our Paganism by what it is not, I think it is necessary in a theoretical definition.

Certainly, we should not depend on being defined from the outside. On the other hand, within the Western context – which is by default set in some variety of Judeo-Christianity – we have little choice but to make this distinction.

Seeking the Spiritual and Sacred Other

Paganism is certainly more than simply what it is not. This broad field of “Western and not Judeo-Christian” is not a whole definition. We can take this still-broad field of practices and experience and divide it further.

While both Paganism and the New Age are attempts to recapture the spiritual and sacred other, Pagans attempt to unearth an “other” in a cultural or historical past. The New Age, by contrast, attempts to capture a different kind of “other” – one defined by geography and culture.

We can never know what the lost Western paganisms truly looked like. And without engaging non-Western beliefs in their original context, Westerners will forever try and fail to grasp non-Western beliefs in attempts to revitalize our own spirituality.

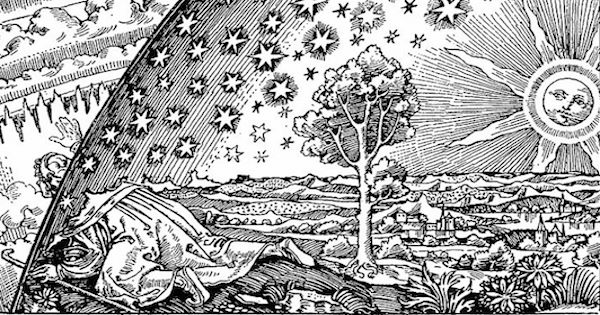

Still, at their best, these two – Paganism and the New Age – are honest attempts to grasp a spiritual and sacred other outside the realm of Judeo-Christianity. Western Paganism is a way of encountering and interacting with the spiritual and sacred “other” through a prism of a past that is Western but not Christian. It is, at its root, a revitalization movement.

Paganism is an attempt to recapture something thought long lost in the West. The impetus to do so is, I believe, a visceral and necessary one. After two millennia of religious monoculture, the West lost access to some of the wonder of the spiritual and sacred universe. Paganism is an attempt to get it back.

———–

(1) The position that words mean whatever we want them to mean is technically true, for some definitions of “we.” This observation, while clever, is as useful as any sentence that begins with the word “technically,” as described in the web comic XKCD here.

(2) In short a revitalization movement is a “deliberate, organized, conscious effort by members of a society to construct a more satisfying culture”.

(3) I use the phrase “spiritual and sacred other” consistently in this post, and in line with my other posts, as a replacement for “the numinous.” I have been looking for a replacement for “numinous” since reading Rudolph Otto’s The Idea of the Holy.

Otto’s conception of the wholly (and holy) other is completely bound with the notion of a transcendent other. It is inconsistent with my experience of non-transcendent spirituality. In short, the term numinous works perfectly for Christianity. Its utility for Pagans is limited unless we redefine its underlying assumptions. I would rather avoid the term entirely, distinguishing between the spirit and the sacred soul.

(4) E.B. Tylor, the founder of both anthropology and the first evolutionary model of religion, argued that the primary purpose of all religion is as an explanatory system for the world around us. For him, all religion was proto-science, to eventually be replaced by science itself.

(5) A Shintoist might be considered a (lowercase “p”) pagan in some circumstances, and in addition could be a Pagan separately. For numerous examples of the latter, see Megan Mason’s blog, Paga-Tama.

(6) I am not trying to wipe away any consideration of Christian/Pagan hybrid religious sects. Most of these syncretistic beliefs are meaningful in their own context and culturally interesting and informative. But to lump them into Western Paganism is to avoid deeper divisions that I suspect these practitioners are attempting to resolve.