In what follows, you will read an “academic paper” in which I explore some elements of open theism (the link is to a brief introduction to open theism). This is a view of God’s foreknowledge that is controversial, but still in the evangelical family of belief. The most well known Christian leader who holds to this view is Greg Boyd. This will be a nine part series.

—————————————————————–

Context into which Genesis 22 Speaks

Imagine that you are in the midst of an empire that is not your own. Instead of choosing to live in this strange land, you endure captivity, longing for home. This was certainly the case when Israel (and Judah) found itself in exile. The people of God were in a true bind. Prophets reminded these sojourners that their people were still the special son of God who would still partner with God in creating the future. Yet, this hope seems a bit distant. What stories would your people read in order to keep the faith that a better reality could break in at any moment? One such historical tale would certainly be the passage at hand.

In many ways, the context of exile was a mirror to the plight that faced Isaac. Israel experienced the judgment of death to their nation by God, but in spite of this the prophet Jeremiah testified that they would not be completely destroyed “because I [God] am Israel’s father, and Ephraim is my firstborn son” (Jeremiah 31.9). “As Isaac was saved from death, so was Israel delivered from the brink of annihilation.”[1] Even with this hope that God would bring them into liberation, the painful realization was that they chose the exact opposite path of their father Abraham. He chose obedience in the greatest of paradoxical circumstances; they chose idolatry by climbing up the mountain to make sacrifices to pagan deities. Abraham demonstrated everything exilic Israel failed to be.

Not only did this narrative speak to Israel’s eventual situation in exile, but most certainly spoke to the generations prior to the calamity. For those who see Genesis through the lens of the documentary hypothesis (and its developments) chapter 22 fits in the “E” tradition, which “suggests an original pre-Israelite setting.”[2] Those who carried the stories prior to exile, this particular one dating somewhere between 2200 BCE to 1200 BCE, orated this incident because it had significance to the people of God immediately following the time of Abraham as well.[3] Abraham’s descendents looked back at the covenant that was confirmed because of his obedience to God’s difficult command (see v. 15-19), and looked forward to the unfolding future that was theirs to create in continuity with the promise revealed at the end of the test. God told Abraham the result of his obedience would be that “through your offspring all nations on earth will be blessed, because you have obeyed me” (Genesis 22.18). This text is one that spoke to those of pre-Israel, to those in exile, to New Testament times, and throughout history into our day. Genesis 22 is a passage that keeps on speaking as it invites us to see the promises for the open future of Abraham to be realized through the people of God who find their roots in that covenant.

Structure and Rhetorical Strategy of Genesis 22

The structure of the story in Genesis 22 can be observed from a variety of angles, but the principle narrative is confined to the first thirteen verses. Verse 14 looks back at the incident retrospectively and is not helpful for analyzing the composition of the event. The verses that follow (15-19) reflect the result of Abraham’s obedience, God’s confirmation of the covenant.[4]

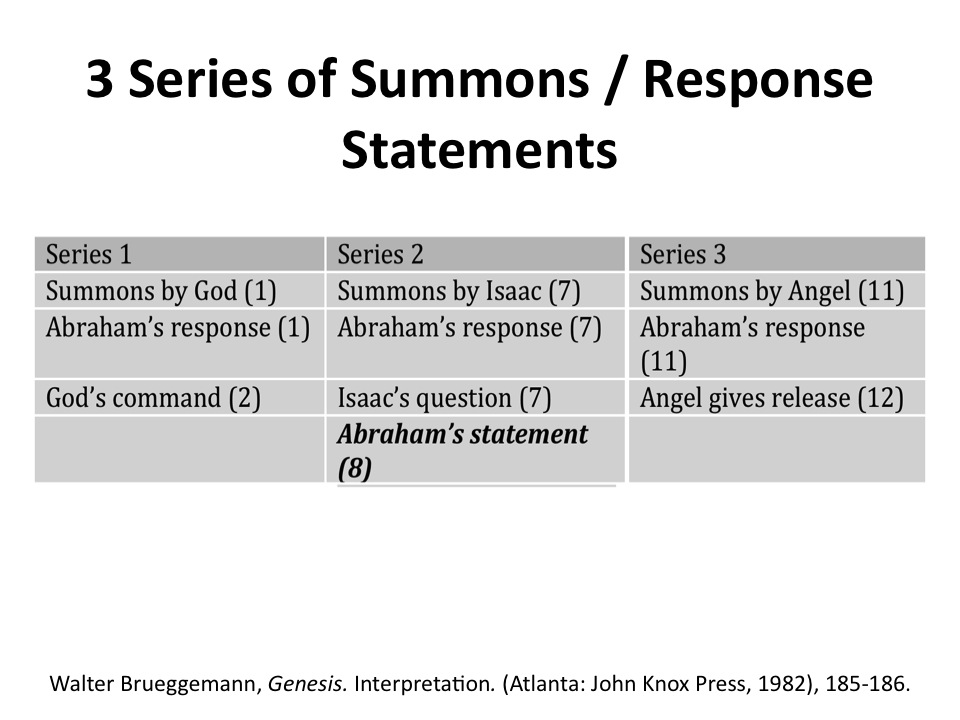

One way to look at the structure of the narrative, which we have called, “the binding of God,” is to note that the text is organized into three series of summons and response statements. Consider the following arrangement:[5]

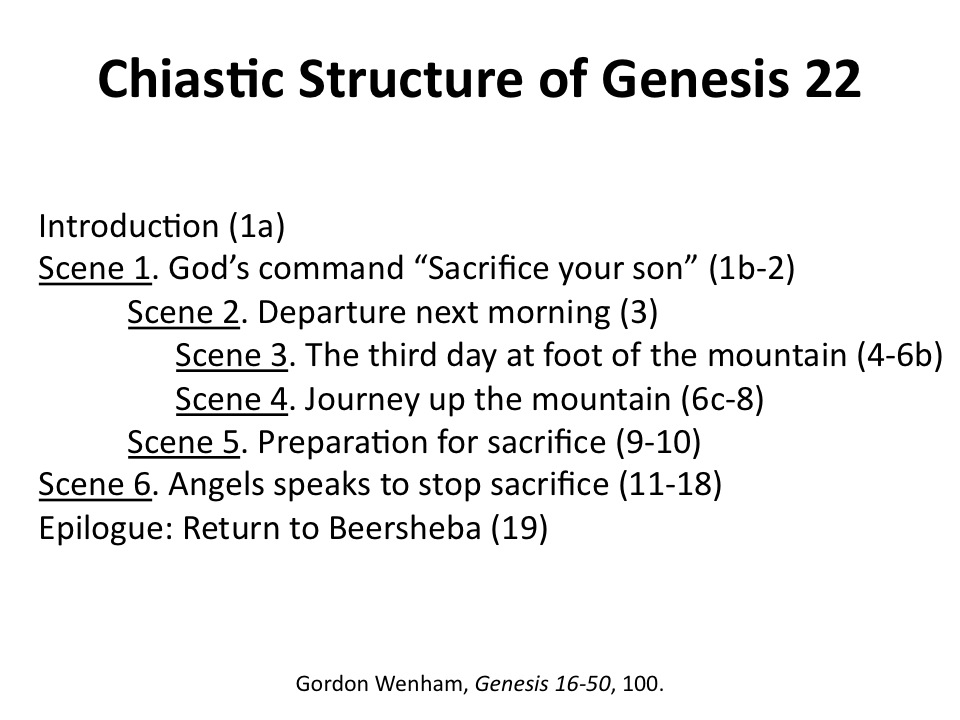

What this chart helps identify is that the first and third series of conversation follow the same basic flow: 1) summons, 2) response, and 3) address. Oddly, the second series adds a fourth component structurally that causes verse 8 to stand out all on its own. Consider a chiastic structural outline of the passage, which verifies the centrality of verse 8 as well:[6]

Even in chiastic configuration the story places verse 8 as part of the center. Not only so, but there is a parallelism taking place between what we might call scenes 1 and 6.[7] The command to – “Take your son, your only son, whom you love…” – in verse 2 finds resolution in verse 12 when God tells Abraham: “…you have not withheld from me your son, your only son.” This is the story within the story. Brueggemann states:

These two verses provide the limits of the drama. The first creates the crisis. The second resolves the crisis. The actual crisis takes place between verses 2 and 12 and is articulated in verse 8… Thus, verse 8 stands between and plays against verses 2 and 12. Verses 2, 12 express the inscrutable intention of God. We know no more about the resolution of verse 12 than we do of the command in verse 2. We do not know why God claims the son in the first place nor finally why he will remove the demand at the end. Between the two statements of divine inscrutability stands verse 8, offering the deepest mystery of human faith and pathos.[8]

Clearly the author of this narrative intentionally brings to the reader’s attention this assurance proclamation, from Abraham to Isaac: “God himself will provide the lamb for the burnt offering, my son.” It is as if Abraham knows a deep level that God’s faithful action will transcend the paradox. Nowhere in the text is it suggested that Abraham here is lying to Isaac. Abraham “conveys to Isaac what he believes to be the truth about his future.”[9] God is the one Abraham believes must provide a way through the situation consistent with his character,[10] which is another indication that God is the one in the greatest bind of all. God needs to see if Abraham will be faithful so redemption can move forward, but he is also bound to his own faithful disposition.

[1]. Terence E. Fretheim, Genesis. The New Interpreter’s Bible: A Commentary in Twelve Volumes, ed. Leander E. Keck et al. (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994), 1:499.

[2]. Fretheim, Genesis, 494.

[3]. Gorden J. Wenham, Genesis 16-50. Word Biblical Commentary, ed. David A. Hubbard and Glenn W. Barker, 2nd ed. (Waco, Tex.: Word Books, 1982-<2004>), xxi.

[4] For our purposes, we will not be looking at verses 20-24 as they present a genealogy outside of the textual unit at hand.

[5]. Walter Brueggemann, Genesis. Interpretation. (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1982), 185-186.

[6]. Wenham, Genesis 16-50, 100.

[7]. Ibid.

[8]. Brueggemann, Genesis, 187.

[9]. Fretheim, Genesis, 496.

[10]. Wenham, Genesis 16-50, 109.