The following series is based on my senior paper for Seminary. You may remember a video where I invited people to contribute their stories to help make my case. For the next couple weeks, I’ve decided to share my findings with you all. There will be a “thesis/problem” section, a “biblical theology” section, and an “application” section. I hope you will read along and share this with others! You can read the rest of the series here.

—————————————————————————————

Evolving Evangelicalism: Inviting Church Leaders to Refine their Approach to Scripture and Origins (part 4)

BIBLICAL THEOLOGY

Scientific developments, particularly within the study of biological evolution, create an opportunity to dig deeper into the biblical text. In doing so, we will not seek to redefine Scripture to accommodate for science, but rather will be interested in the task of refining our interpretations with the utmost regard for biblical authority. We will begin by exploring one of the most beautiful, Holy Spirit-inspired passages in all of the biblical narrative: Genesis 1. We will then investigate Adam and Eve’s historicity. The following interpretation, while incomplete, provides a model for maintaining the biblical authority of the book of Scripture while also maintaining an open posture toward modern views about the book of nature.

Genesis 1 and Creation

In the beginning… there was conflict. The chaotic waters of the deep in verse 2 remind us of our cultural quarrels generating from interpretations of Genesis 1. The following approach attempts to demonstrate that this passage is not describing how the world was made, but instead declares who organized the world to function with purpose.

The Structure and Style of Genesis 1

Many interpreters of Genesis 1[1] appeal to the text as a work of poetry. The way poetry usually functions is to point to larger ideas, not to convey a literal lists of facts. In this case, some say that if the first chapter of Scripture is indeed poetic, then it demonstrates that: God created; humans bear the image of God; and God intimately loves what God made and declares all creation “very good.”

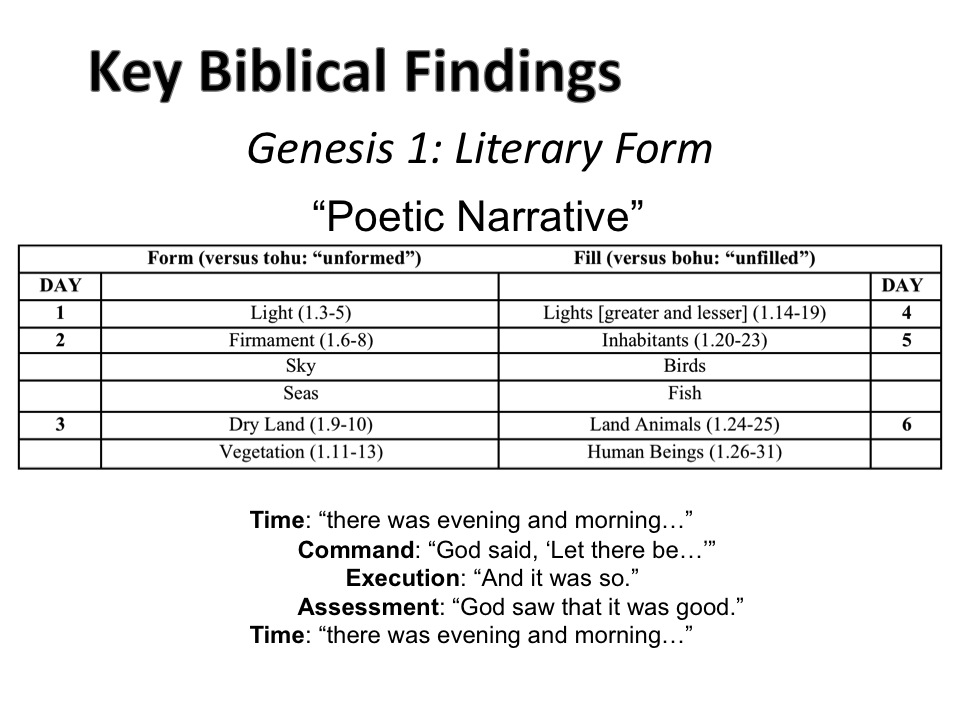

It is evident that the writer of Genesis 1 chose stylistic prose. However, the pericope uses a sequential future verb form throughout, which is the typical marker of an Old Testament narrative text.[2] Therefore, it uses a unique form that Walter Brueggemann calls “poetic narrative.”[3] This passage was probably utilized as a liturgy of Israel,[4] evidenced by its “doxological character,”[5] which may explain why the text is both poetic and narrative in form.

The following outline demonstrates the poetic stylizing of Genesis 1:[6]

| Form (versus tohu: “unformed”) ———- Fill (versus bohu: “unfilled”) | |||

| DAY | DAY | ||

| 1 | Light (1.3-5) | Lights [greater and lesser] (1.14-19) | 4 |

| 2 | Firmament (1.6-8) | Inhabitants (1.20-23) | 5 |

| Sky | Birds | ||

| Seas | Fish | ||

| 3 | Dry Land (1.9-10) | Land Animals (1.24-25) | 6 |

| Vegetation (1.11-13) | Human Beings (1.26-31) | ||

It becomes obvious that the various days of creation parallel each other. Day 1 goes with day 4, 2 with 5, and 3 with 6. For this reason, many people who challenge the 7-day perspective ask how 24-hour days were marked when the sun was not created until day 4. That is one of many benefits to paying close attention to form.

The “poetic narrative” also demonstrates another pattern:

Time: “there was evening and morning…”

Command: “God said, ‘Let there be…’”

Execution: “And it was so.”

Assessment: “God saw that it was good.”

Time: “there was evening and morning…”

Both the framework of the days and the patterns of the command-execution sequences exhibit the passage’s literary intentionality.[7] Genesis 1 as “poetic narrative” (or liturgy) demonstrates that it was written with intent, not merely as a list of literal descriptions about how the world came into existence.

Yet, we must also recognize the temptation to dismiss this passage as only poetic. Many who claim a form of theistic evolution are content to stop there. Such an interpretive approach irresponsibly neglects the need for further theological inquiry, based on genre related issues. Knowing that Genesis 1 is both narrative and poetry invites careful interpreters to discover the various nuances of meaning beyond the broad truths that God created and humankind was made uniquely in God’s image. Integrity to the complex literary form (not to mention biblical authority) pushes us to think more deeply about the theological purposes and authorial intent of the first chapter of the Bible.

[1]. Genesis 1 in this paper actually refers to the textual unit of Genesis 1.1-2.3.

[2]. Prior to taking Hebrew in seminary, I took for granted that this text was purely poetry.

[3]. Walter Brueggemann, Genesis, Interpretation: a Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching (Atlanta: John Knox Press, 1982), 22.

[4]. John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2009), 91.

[5]. Terrence E. Fretheim, The New Interpreter’s Bible: A Commentary in Twelve Volumes – Volume I, Genesis (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1994), 341.

[6]. Bruce K. Waltke, Genesis: A Commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan, 2001), 57.

[7]. Brueggemann, Genesis, 30.