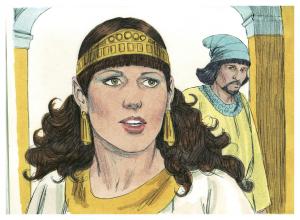

Most of us know one memorable verse from the late story of Esther, 4:14: “Who knows whether you may have come to royal power for just such a time?” Mordecai is in effect telling his niece, the extraordinarily beautiful and secret Jew, Esther, that she has a real chance to save her people from the absurd and unpredictable king of Persia through the murderous designs of one of his chief henchmen, Haman. He demands that she confront the king with the plot of Haman to annihilate all the Jews, because he, Mordecai, has refused to honor the narcissistic courtier, leading Haman to hate all Jews and to seek their destruction. But Esther knows that if the king is having a bad day, or simply refuses to speak with her, she can readily be forgotten and killed at his whim. Nevertheless, Mordecai warns her, she will not escape Haman’s plot, even if she tries to shirk her duty as a Jew and as queen. In a series of very clever plots of her own, Esther wins the day, Haman is hanged on the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai, and the Jews of Persia are spared.

Most of us know one memorable verse from the late story of Esther, 4:14: “Who knows whether you may have come to royal power for just such a time?” Mordecai is in effect telling his niece, the extraordinarily beautiful and secret Jew, Esther, that she has a real chance to save her people from the absurd and unpredictable king of Persia through the murderous designs of one of his chief henchmen, Haman. He demands that she confront the king with the plot of Haman to annihilate all the Jews, because he, Mordecai, has refused to honor the narcissistic courtier, leading Haman to hate all Jews and to seek their destruction. But Esther knows that if the king is having a bad day, or simply refuses to speak with her, she can readily be forgotten and killed at his whim. Nevertheless, Mordecai warns her, she will not escape Haman’s plot, even if she tries to shirk her duty as a Jew and as queen. In a series of very clever plots of her own, Esther wins the day, Haman is hanged on the gallows he had prepared for Mordecai, and the Jews of Persia are spared.

Little wonder that this romantic and ultimately cruel and dark tale soon was taken as the very model of Jewish survival in foreign lands. At the yearly feast of Purim (a word meaning “lots” in Hebrew), Jewish children still reenact this drama for the delight and applause of their parents; the Jews win and the bad guys are defeated. However, as history recounts all too grimly, such an outcome was exceedingly rare. Too often, the Jews were either slaughtered or expelled from country after country, culminating in the insane butchery instigated in Hitler’s Germany during the Shoah, the “annihilation,” better known as the Holocaust. The text for today offers the scene wherein Haman is discovered as the evil man he is, and is duly dispatched on the absurdly tall gallows (50 cubits, some 80 feet!), while Mordecai and Esther are once again found to be in the good graces of the unpredictable Ahasuerus. End of story?

Not quite. In a nasty switch in chapter 8 Esther entreats the king to allow her to abrogate the command of Haman to kill all the Jews throughout all the provinces of the Persian Empire. The king does exactly as she asks, but goes much further. On a certain day of the year, the 13th day of Adar, the last month of the Jewish calendar, Ahasuerus commands that the Jews have the right to “destroy, kill, and annihilate” any one who dares attack them, thereby, “taking revenge on their enemies” (Esther 8:11-13). Whether the author of the tale means the war is a defensive one or something rather more offensive has been the source of much debate over the years. In any case, Haman’s desire to annihilate the Jews is now matched by the Jew’s willingness to annihilate their enemies. And as a result of this edict, “many of the peoples of the country professed to be Jews, because the fear of the Jews had fallen upon them” (Esther 8:17).

There is much to be thought about in this ancient story. The courage of Esther is usually applauded, and she is held to be a model of female power. The survival of the Jews is held up as a positive hope and possibility in the face of numerous pogroms against them over the centuries. The fact of the Jewish defeat of their enemies and the forced conversion of many Persians to Judaism engenders troubling ideas. All three of those themes are worthy of serious reflection, and I leave them to you.

Today, I am concerned with the dangers of bigotry that led Haman in the first place to despise all Jews. The author of the tale gives to us a primer for the origins of raw bigotry. For that we turn to Esther 3. Haman is first promoted to be chief official in the kingdom, and as a sign of his magnificent stature, Ahasuerus commands that whenever Haman appears in public all will immediately bow down and “do obeisance” to him. That latter verb is more specifically “to fall on one’s face before.” Such is the grandeur and magnificence of Haman that no one is allowed to see him, but must avert their eyes and face only the ground. Only Mordecai refuses to bow to Haman, and though many adjure him to bow, he refuses, announcing to them that he is a Jew.

At this point in the story, we might imagine that the fact of Mordecai’s Judaism would be his reason for refusing to bow to Haman, thus fulfilling the law of worship of YHWH alone. Surprisingly, perhaps, that is not the reason given. In fact, the name of God is not mentioned a single time in the entire book! Thus, it may be concluded that the only reason Haman despises Mordecai is not merely his Judaism but his refusal to knuckle under to his supposed greatness. There we find the root of his bigotry against Mordecai. Yet there is one more step to take. Haman feels himself so superior to Mordecai that “he is ashamed (literally “shamed in his eyes”) to touch him himself” (Esther 3:6), so instead he transfers his loathing for the man to all of those who are like him, namely the Jews. First, Haman judges Mordecai as different in his refusal to act as Haman thinks he should, and then not deigning to confront the man himself, fearing some nameless taint, decides to take out his aggrieved fury on all of Mordecai’s compatriots.

Bigotry, thus, arises from something like the facts of this case. First, one is seen as different, not acting as it is determined that one should act. Next, that different actor arouses anger in the one in control, and in a ridiculous and furious conclusion, all those who are from the same tribe or clan or race or group are assumed to be the same and must be eliminated if the powerful one is to have the world he has determined is the right and just world. All Jews are like Mordecai! All Jews are money-mad and clever and rich! All Mexicans are rapists and gang members! All African-Americans are lazy, refusing to work! All foreigners are different, hence dangerous, and not like us! Keep them out of our country!

The spirit of Haman is alive and well and living in me! How often have I judged all conservative thinkers, those who do not think as I do, pure and helpful liberal that I am, as dangerous and foolish? How often have I judged a person whose skin is not as mine to be hateful and antipathetic to what I want for my life and the life of the world? When I hear another language being spoken around me, how often have I assumed that they are plotting against me, or laughing at me, or speaking of wicked acts? “Love your neighbor as you love yourself,” as the Levitical priests said long ago, along with the startlingly similar “love the immigrant as you love yourself.” Bigotry is defeated only by the conviction that others, however different they may appear, deserve your love and respect every bit as much as you should love and respect yourself. Let us all metaphorically hang our Hamans high and see in others what we hope they see in us.