I wrote several weeks ago that I was beginning a visit to our cabin high in the Santa Fe wilderness primarily in order to view the changing of the aspen leaves from green to gold. I am ecstatic to say that that mission has been accomplished! My wife and I have gazed daily at the ever-changing foliage as it has made its annual transformation. It has been glorious! Two days ago, we had a fluffy snowfall, a fact, I am told, that signals the end of the leaf change and is of course the harbinger of winter. Indeed, the still golden trees now have as a backdrop a snow-dappled Santa Fe Baldy mountain, adding to the visual splendor. We have been here now nearly three weeks, and we could not be happier with the fulfillment of our hopes. We will sadly bid goodbye to this awesome wonder next Monday, Oct.15.

I wrote several weeks ago that I was beginning a visit to our cabin high in the Santa Fe wilderness primarily in order to view the changing of the aspen leaves from green to gold. I am ecstatic to say that that mission has been accomplished! My wife and I have gazed daily at the ever-changing foliage as it has made its annual transformation. It has been glorious! Two days ago, we had a fluffy snowfall, a fact, I am told, that signals the end of the leaf change and is of course the harbinger of winter. Indeed, the still golden trees now have as a backdrop a snow-dappled Santa Fe Baldy mountain, adding to the visual splendor. We have been here now nearly three weeks, and we could not be happier with the fulfillment of our hopes. We will sadly bid goodbye to this awesome wonder next Monday, Oct.15.

Yesterday, during a great visit with some long-time friends, we drove to Los Alamos, and then returned to our place, stopping all too briefly at the Pecos National Historical Park. This place is just outside of the small village of Pecos, and Diana and I have visited it numerous times. It is an excellent location with a superb visitor’s center, and a self-guided trail that winds through what was 500 years ago the site of a huge native American village, boasting a population of perhaps 10,000, living in multi-story log buildings, all of which have disappeared in the ensuing half millennium. What remains are several kivas, holes in the earth that may be visited via crude ladders, a few sand stone foundations remain that probably contained grain stores or livestock, and most prominently a shell of a 1717 Spanish missionary church, standing proudly as a bright red sand stone three-sided edifice that dominates the landscape.

I imagine when the Franciscan monks came to this land late in the 17th century that was precisely their intent: to dominate the land. And so they did for a time, but in 1684, the native population rose against them, both from the community that surrounded the church (thoroughly destroyed and replaced by the present smaller building), and from the nearby pueblos. They timed their revolt by the ingenious method of using identical knotted ropes, taking a knot away for each passing day, and rising up when the ropes’ knots were all finally untied. The massacre that ensued was terrible, and bought the indigenous population a measure of freedom for a time, but in the end the invaders regained the upper hand, and the natives were again subdued and oppressed.

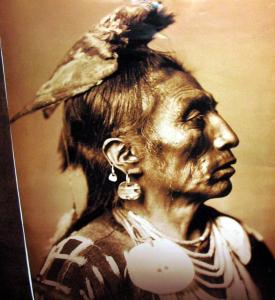

This scenario was played out multiple times over the succeeding centuries in most of the western states: Arizona, California, Utah, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and in many states further east. Again and again, native populations were driven off their land or decimated or forced into slavery, or all three. As I again stood within the shell of that 300-year-old Franciscan church, I recalled not for the first time the horrors of the various assaults unleashed on Native Americans during the 200 year “conquering of the West.” When I was in grade and high school, that story was told in such a way that the vast tragedy and near extinction of the first persons on the continent were downplayed in favor of the shining heroics of the traders and trappers and soldiers who in effect were the authors of that horror. I have now read numerous accounts that describe in appalling detail the travesties of the “winning of the west.”

My reflection was brought on by another “celebration” of what is still often called Columbus Day, but in the city of Los Angeles where I live, along with other American cities, is now referred to as “Indigenous People’s Day,” a small attempt both to redeem the monstrous actions of the Italian navigator, perpetrated on the native populations of various Caribbean islands, and the slaughter of so many natives during the white people’s drive to “tame the west.” Despite an article that I read just this week, attempting again to redeem the reason for Columbus Day, a name esteemed by the vast number of Italian- Americans in the US, who celebrate the day as part of the redemption of their people who came to America and were publically scorned and derided by Americans already here, I cannot join their pleasure at the name of Columbus. Any history of the man describes his torturous treatment of those he met during his search for the fabled “passage to India,” while he attempted to conquer more of the world for Spain and its domineering monarchs, Ferdinand and Isabella. It is hardly a coincidence that the very year that Columbus, an Italian searching desperately for a sponsor for his voyage of conquest, made his first voyage, that the Spanish king and queen expelled from their country on pain of death all Jews whom they determined were eternal enemies of Christianity. Thus, both Columbus and his patrons were equally implicated in calumny against peoples they determined were “Others,” unlike them and hence expendable.

Any celebration of Columbus Day is at the same time a celebration of conquest, destruction, and western hegemony. We do well to expunge such celebrations from our calendars and to replace them with occasions that lift up unity, the wholeness of humanity, the oneness of the earth’s diverse family. Gazing at that ruined Franciscan church reminded me again that we have a long way to go to realize that dream of wholeness that usually appears so far away as to be unattainable in this life.

But we Christians can never be pessimists in the face of such wretched realities. In the acrid political and social climate of 2018, fueled by an unrestrained and overtly racist president and his cronies, as well as a body politic that would rather hurl acrimony than seek useful discussion, those of us who follow the Prince of Peace, the one sent by God to “save” us, though that delightful and much misunderstood word actually means to “be made whole,” must always be about the business of healing wounds, not forcing them open, must concern ourselves with the search for ways to unite rather than divide. We cannot turn back the clock on the horrors of the past, but we can keep up the search for new ways to ask for and to effect “the rule of God on earth as it is in heaven.”

(images from Wikimedia Commons)