I doubt any biblical text could be more relevant in this particular time in history than this scorcher from Amos. Of course, Amos is hardly a shy retiring violet when it comes to boldness and irritation for his hearers, but this small prose section in the midst of his scathing oracles is especially memorable, and especially uncomfortable for its targets. The text is directly about the muddled question of the separation of church and state, an issue that zombie-like cannot be killed off in our or any other time.

I doubt any biblical text could be more relevant in this particular time in history than this scorcher from Amos. Of course, Amos is hardly a shy retiring violet when it comes to boldness and irritation for his hearers, but this small prose section in the midst of his scathing oracles is especially memorable, and especially uncomfortable for its targets. The text is directly about the muddled question of the separation of church and state, an issue that zombie-like cannot be killed off in our or any other time.

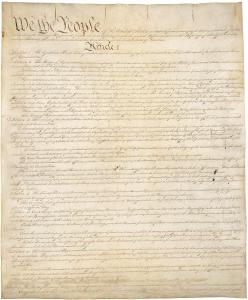

It is particularly propitious this year on this date to address this complex question. Today is Bastille Day in France, that terrible and wonderful day when the French Revolution began with the storming of the infamous prison, the Bastille, and the release of numerous prisoners, many of whom were incarcerated due to the overwhelming power of the church, hand in hand with the monarchical state. The reality was, of course, that this grand day of freedom was followed by the monstrous Reign of Terror that roiled France for too many years. However, the upshot of the entire episode was the near complete secularization of the country, as priests were laicized en masse, churches were closed, and religion was banished from the wheels of state power. Here was a complete separation of church and state writ large, and the upheaval was hugely important for the organization of the fledging American government. After all, both Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson learned enormously from France just how to establish a government that tried mightily to keep any vestige of religion from determining how a state should order itself. The potent Establishment Clause of the Constitution was designed specifically to reject any attempt on the part of any one religious belief to demand hegemony over all other religions or to insist that its particular beliefs and practices should in any way determine how the state should govern its citizens and how those citizens should live.

This is hardly to say that American religious people have not tried again and again to force their religious views on the government, whether federal, state or municipal. These attempts are particularly powerful right now, when several states have enacted strict anti-abortion laws in direct challenge to the settled law of Roe v.Wade that demands that safe abortion be made available anywhere in the country. These laws are based squarely on particular religious viewpoints not shared by everyone in the US. When now 25% of our citizens claim no religious affiliation at all, and there are significant numbers of Muslims, Jews, and Hindus, among many other traditions amply represented here, those more conservative Christians, Catholic and Protestant, who hold a strict anti-abortion stance, appear certainly to be trying to impose that belief on all of us. It seems on its face to be a clear violation of the above-named Establishment Clause in the Constitution, but I assume that eventually the question will find its way to our Supreme Court that 45 years ago made abortion legally available for all Americans.

However all that plays itself out in the halls of government and the chambers of the High Court, the issue at stake remains the same: just what is the relationship between church and state in our common life? The prophet Amos has something to say about this issue some 2700 years ago, a fact that never fails to astonish us who stand in his debt. But first a clarification is in order. Amos plied his prophetic work in a state that was plainly not democratic and was not ordered by an agreed-upon document like our Constitution. Both Israel and somewhat later Judah were obvious monarchies, ruled by a king who was, at least it was claimed at his coronation, chosen by YHWH. However, unlike the nations that surrounded Israel—Egypt, Syria, Babylon, Assyria, etc.—the written texts of Israel felt quite free to call the monarchy into the most serious question, depending on whether the current king was seen in reality to be a representative of YHWH or was viewed merely as a person of power who attempted to do whatever he wanted, despite the received demands of the God of the land. Few of the kings of Israel and later Judah get a pass from the texts when it comes to their adherence to the will of YHWH. Even though David is long remembered as the greatest king in Israel’s history, that fact did not deter in the least the author of his story from painting him as far less than completely righteous and virtuous; he does, after all, break four of the Ten Commandments in only one of his stories!

So, when Amos excoriates the king of Israel, presumably Jereboam II, as he is named in Amos 7:9 and 7:11, he stands in a long line of those dissidents in Israel who are decidedly uncomfortable with rulers who claim more power for themselves than they ought. Amos, a wealthy shepherd of Tekoa (the word used to describe him in 1:1 means more than a simple herdsman with a few scruffy sheep), heads north to the main sanctuary of the northern kingdom, Bethel, and proceeds to launch a scathing attack on the oppressive well-to-do in the land who crawl off to worship soon after they have fleeced the poor and laughed all the way to the bank. Amaziah, the High Priest in Bethel, listens to a brief bit of Amos’s most recent sermon and has had enough of the loud- mouthed little twerp. “O seer (a word that may be heard as “soothsayer,” or “crystal ball gazer”), leave, flee back to the land of Judah (Amos’ homeland), earn your bread there (Amos is obviously saying all this for financial reward), prophesy there; never again prophesy at Bethel, for it is the king’s sanctuary; it is certainly the temple of the kingdom” (Amos 7:12-13). And there is the chief problem in today’s text.

Amaziah, the High Priest, supposed representative of YHWH, called by God to lead and instruct the faithful at the central sanctuary of the northern kingdom, has clearly and forcefully announced that in fact his place of service is not YHWH’s at all; it is the sanctuary of the king, as much as his throne room is, as much as his audience chamber may be. Even the church is not God’s church; it is the place of the king’s power, that place where the king’s edicts are given the divine seal of approval, where what the king decides is in effect what God has decided.

And with that we are back in the muddle of the relationship between the church and the state. Amaziah has decided the question on the side of the state; this is the king’s place, he says. Gaze at his throne chair in the front of the sanctuary, Amos, and know that nothing you say can possibly be from God. Yet, if Amos has been called by YHWH, and is attempting to utter words that YHWH has given him, just how are we to adjudicate who is the divine spokesperson? Who finally has the right to speak for God? That complex question is the very reason why church and state must maintain its “high wall of separation,” to quote Jefferson. Once the church is allowed to determine how all must live and believe, the wall has collapsed and one religious perspective only has taken over.

This is seen again and again in modern America, from treatment of LGBTQI persons, to a person’s right to deny services to anyone whom the supplier of those services deems antagonistic to the servicer’s beliefs, to Christian prayer in schools and government meetings (does it strike you as decidedly odd that there is still today a “chaplain of the Senate” who prays before gatherings, gatherings peopled by believers and non-believers alike?). I have always found it frankly absurd that I, as a clergyperson, must sign marriage licenses before they become legal documents. How is that not a deep entanglement of church and state?

Old Amos made it clear that God must not be usurped, used, by the state in order to lend some sort of divine credence to whatever it has decided to do. For Amos, the corruption of the people and state of Israel would not finally escape the dark opprobrium of a YHWH who demanded justice and righteousness for all God’s people, not just a powerful few. Sure enough, that state ended with the attack of the Assyrians, some 30 years after Amos’s words were spoken. I do not imply by that statement that nations that intermingle church and state are automatically doomed to collapse, but it may be wise for us on this day to “Remember the Bastille!” Nations that confuse the power of God with the power of the state do, it seems, do so at very great risk.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)