Preachers and teachers need poetry. I do not mean by poetry the insides of greeting cards or the doggerel of the most popular hit tune—though certain hip-hop hits can be instructive and useful as cultural artifacts. What I do mean is poetry that enlivens, challenges, puzzles, and generally offers language that surprises, shocks, and thrills the ear. The preacher’s basic tools are words, and poets major in words, their power and their wonder.

Preachers and teachers need poetry. I do not mean by poetry the insides of greeting cards or the doggerel of the most popular hit tune—though certain hip-hop hits can be instructive and useful as cultural artifacts. What I do mean is poetry that enlivens, challenges, puzzles, and generally offers language that surprises, shocks, and thrills the ear. The preacher’s basic tools are words, and poets major in words, their power and their wonder.

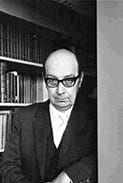

Back in my formal teaching days, I enjoyed teaching a class that I called “Preaching and Contemporary Literature.” I defined “contemporary” rather loosely, using novels and plays composed over the previous 100 years at least. And I used poetry, smidgeons of Robert Frost and T.S Eliot, among other lesser-known authors. However, each time I taught the class, I always used the work of Philip Larkin. There was just something about his acerbic observations of English life that spoke right to me, and, I found, to my very American students as well. I chose the word “acerbic” carefully to describe what Larkin was doing in his poetry. He was both sharply attuned to events and places, but also saw them with a wry wit, a sometimes jaundiced eye. And yet at regular intervals, the light of love would come shining through some of his work. It is notable that so many of his contemporaries judged him to be a dark and dispiriting figure, given over to a pessimistic view of things, but I think that is a far too limited view of the man.

He was born in 1922 and died in 1985, having spent the whole of his professional life as the University Librarian at Hull College. He was certainly well known as a poetic luminary during his life, but eschewed most of the traditional public demands of an English author. Just before his death, he was offered the post of Poet Laureate of England, but rather harshly turned down the position. What attracts me to his poetry is that element of surprise, the shaft of insight among seemingly mundane-sounding language. I have long believed that we preachers could learn much from such a careful observer of common things. By that I do not mean that we should immediately quote great swatches of poetry in our sermons; most of us are not well equipped to declaim in that way, nor are our hearers anxious to listen to lines of blank verse, however much we have been moved by them. Phillips Brooks, that redoubtable 19th century preacher regularly filled his sermons with oodles of Shakespeare, but he was speaking to an upper- middle class congregation who often spent their Sundays reading the bard to one another as families. Those days, for good or ill, are long gone.

What Larkin, and other poets like him, can do for us is to sharpen our eyes, to deepen our surveillance of our own lives, to open ourselves wider to the connections of things, to discover that what we see on the surface is not all there is; in fact, what we too easily see may not be the crucial thing that we ought to be seeing. Let me offer a few examples from Larkin’s work.

His 1956 poem “An Arundel Tomb” finds him visiting the old Wessex market town, Arundel, and stepping into the small cathedral there. His eye moves toward a very common sight in such English places, the statues of an old earl and his countess, lying prone in their armor, fixed forever in marble. Nearly every church of any size in England has a similar sight to be looked at and quickly forgotten. But the poet finds more. He observes “that faint hint of the absurd—the little dogs under their feet.” “Such plainness of the pre-baroque Hardly involves the eye, until…” And with that “until,” the sharp observational poet shifts into a higher gear. He looks further and notices the earl’s “left- hand gauntlet, still clasped empty in the other; and one sees with a sharp tender shock, His hand withdrawn, holding her hand.” “They would not think to lie so long, in such faithfulness in effigy. And the final stanza makes the point:

Time has transfigured them into Untruth. The stone fidelity

They hardly meant has come to be;

Their final blazon, and to prove Our almost-instinct almost true:

What will survive of us is love.

The marble statues, probably intended to be a witness to the power of the lord of the town, forever frozen in that power, expecting fully that it is power that will be their epitaph, have instead ttaught the poet who visits centuries later “what will survive of us is love.” Though Larkin was not a traditional believer by any stretch, yet he has here named what defines a believer most clearly, caught in a marble memorial.

Perhaps my favorite Larkin poem is his 1954 “Church Going”. I believe that every preacher should know and treasure this poem, for it names and summarizes what makes church both dangerous and crucial. It is too long for full examination here, but the plot may be quickly recounted. The poet has bicycled his way to another near-derelict English church. I lived in England for a year some 25 years ago, and I saw more than a few closed churches; if they had not become much-sought-after flats for the newly rich, they stood gathering dust down one country lane or another.

“Once I am sure there’s nothing going on

I step inside, letting the door thud shut.

Another church: matting, seats, and stone,

And little books; sprawlings of flowers, cut

For Sunday, brownish now, some brass and stuff Up at the holy end; the small neat organ;

And a tense, musty, unignorable silence, Brewed God knows how long. Hatless,

I take off My cycle-clips in awkward reverence,

Move forward, run my hand around the font.”

I am tempted just to quote the whole thing, since its word choice is so superb, so careful. The poet only enters when he is sure “there’s nothing going on.” Exactly what does “go on” in a church, he implies, and the answer may be nothing. But not so fast! After the second stanza ends with the line, “Reflect the place was not worth stopping

for,” he goes on to say, “Yet stop I did: in fact I often do, and always end much at a loss like this, wondering what to look for.” As a clear outsider to all this church business, what should he look for? When strangers wander into our buildings what should they look for? His answer is surprising.

“What this accoutered frowsty barn is worth, It pleases me to stand in silence here.

A serious house on serious earth it is,

In whose blent air all our compulsions meet,

Are recognized, and robed as destinies.

And that much never can be obsolete,

Since someone will forever be surprising

A hunger in himself to be more serious,

And gravitating with it to this ground,

Which, he once heard, was proper to grow wise in, If only that so many dead lie around.

It turns out that a great deal is in fact “going on” in the church that remains “a serious house on serious earth.” And even if one is initially drawn to the place simply because “so many dead lie around,” in coming at all one might be surprised to find “a hunger in himself to be more serious.” I find that not a bad definition, however limited, of what church should be about, a place to discover a hunger for seriousness. Larkin helps me to see things I cannot see on my own.

Poets can do that. I commend them to you, as you seek to deepen and sharpen your ways with words that can move and surprise your listeners into a new seriousness of their own.