One of the deep ironies of the story of Job is that the ongoing dialogue is driven by characters that wish the others would simply shut up! When the friends first encountered Job on his ashy heap, they sat in silence, observing his agonies, convinced that he was in his terrible state due to his obviously disgusting sins against God. For them, no one ends up like Job unless they have performed unmentionable evils, because God without fail punishes such actions. They expect Job to die without comment, receiving his just desserts from a God who always acts against the sinner. However, Job, far from remaining silent and accepting of his fate, proceeds to scream that he wishes he had never been born, or that he were dead, and finally wondering whether life has any meaning at all (Job 3). This speech goads Eliphaz to reveal his true beliefs and his clear detestation of the foul Job. Though any number of readers have claimed that Eliphaz begins his first speech to Job out of courteous regard for the sufferer, I tried to demonstrate in my previous essay that his words actually were sharp-pointed barbs against him, employing language familiar from the prologue that made it certain that Job was not a sinner in the least, but rather was the most pious and righteous man on the planet. Either Eliphaz is aware of the true nature of Job as righteous, which would make Eliphaz to be a monstrous liar, or he is unaware of Job’s righteousness—the more likely possibility—and he is then a bumbling fool, worthy of rejection and ridicule in equal measure. His ultimate fate in the story will be precisely both rejection and ridicule.

One of the deep ironies of the story of Job is that the ongoing dialogue is driven by characters that wish the others would simply shut up! When the friends first encountered Job on his ashy heap, they sat in silence, observing his agonies, convinced that he was in his terrible state due to his obviously disgusting sins against God. For them, no one ends up like Job unless they have performed unmentionable evils, because God without fail punishes such actions. They expect Job to die without comment, receiving his just desserts from a God who always acts against the sinner. However, Job, far from remaining silent and accepting of his fate, proceeds to scream that he wishes he had never been born, or that he were dead, and finally wondering whether life has any meaning at all (Job 3). This speech goads Eliphaz to reveal his true beliefs and his clear detestation of the foul Job. Though any number of readers have claimed that Eliphaz begins his first speech to Job out of courteous regard for the sufferer, I tried to demonstrate in my previous essay that his words actually were sharp-pointed barbs against him, employing language familiar from the prologue that made it certain that Job was not a sinner in the least, but rather was the most pious and righteous man on the planet. Either Eliphaz is aware of the true nature of Job as righteous, which would make Eliphaz to be a monstrous liar, or he is unaware of Job’s righteousness—the more likely possibility—and he is then a bumbling fool, worthy of rejection and ridicule in equal measure. His ultimate fate in the story will be precisely both rejection and ridicule.

Eliphaz ends his first address to Job in Job 5 with a sermonic flourish, promising the repentant sinner—for surely Job must repent of his obvious crimes—that he “will come to his grave in a ripe old age, just like a shock of grain comes to the threshing floor in its due season. Look! This we have investigated; it is true! Listen, and know it for yourself” (Job 5:27)! Eliphaz, the religious mountebank, preaches his simplistic theology that God is in the business of rewarding and punishing, a fact of life that must be accepted without question. Certainly, Eliphaz expects Job to weep in contrition and come to Eliphaz, the proclaimer of truth, for absolution. The last thing that Eliphaz expects is further discussion from the object of his overwhelming preaching.

But that is exactly what he gets. In Job 6-7, the supposed sinner has a flood of commentary directed to the preacher, who is probably not at all used to hearing feedback to his sermons. Several examples will suffice. Eliphaz had warned Job that “vexation (“fury”) kills a fool; jealousy murders a simpleton” (Job 5:2). Job replies, “If only my “vexation (“fury”) were weighed, all my life laid on the scales; it would be heavier than the sands of the sea! That is why my words have been rash” (Job 6:2-3)! While Eliphaz accuses Job of being overly angry and rash, thus presenting himself as a fool, Job replies that his words are rash because he is being attacked. And the source of the assault he makes plain in vs.4: “The arrows of Shaddai are in me; my spirit drinks its poison; the terrors of Eloah are stationed against me!” Who would not be rash when it appears that God has made Job a target of divine terror?

You want me to “return to God,” Eliphaz, quizzes Job, asking God for forgiveness? I will tell you what I want from God! “If only I might have my request, that Eloah would grant my desire; that it would please Eloah to crush me, freeing God’s hand to cut me off” (Job 6:8-9)! Job reiterates his desire to be dead, but this time asking God to do the deed of murdering him. Job then cries out in anguish, “In truth I have no help in me; any resource is driven away” (Job 6:13). He turns next to a frontal attack on the friends, whom he characterizes as “treacherous as a wadi,” in other words like little trickles of water that appear and disappear in the heat of the desert (Job 6:15). Have I ever asked anything of you, he shouts (Job 6:22-23)? “Teach me, and I will shut up, help me understand how I have gone wrong” (Job 6:24). Clearly, Eliphaz’ eloquent and impassioned sermon has had no effect at all. “Now, be pleased to look at me,” he demands, “for I will not lie in your face. Turn around! Let no wrong be done. Turn, I said! My righteousness is at stake” (Job 6:28-29).

Job follows these sharp and direct requests of the friends with a long and anguished screed against the appallingly dark nature of human existence. We are like slaves, he says, “allotted months of emptiness and nights of misery” (Job 7:2-3). In the first section of this tortured speech, he directs his words to the friends. But seeing that he will receive little of value from them, he turns his attention to the God who is apparently the creator of the horror that life has become. “I loathe my life; I have no wish to live forever. Let me alone, because my days are a mere breath” (Job 7:16). Job then riffs on the famous Psalm 8: “What are human beings that you make so much of them, that you set your mind on them, visit them every morning, test them every moment? Why not look away from me long enough for me to swallow my spit” (Job 7:17-19)! Far from the comfort of God’s presence in the psalm, Job finds God’s constant attention oppressive and wishes God would pick on someone else for a time, long enough at least for a quick swallow!

Bildad is forced into speech by these anti-personal and anti-God ravings of the sinner Job. “How long will you say these things, the words of your mouth be a great wind? Does God pervert justice; does Shaddai pervert the right? If your children sinned against God, they were (rightly) delivered into the very power of their evils” (Job 8:2-4). In a truly disgusting assault on Job and his misery, the noxious Bildad defends God’s absolute actions of reward and punishment by pointing to the death of all ten of Job’s children as a parade example of the just retribution of God against their evils. This is so shocking as to be religiously absurd, a classic illustration of how a dogmatic belief can become something exceptionally cruel and monstrous. If Eliphaz demonstrated a hint of subtlety in his attack against Job, Bildad shows no subtlety whatever; he merely directs his theological dogma straight at the sufferer, in some ridiculous attempt to make him see the truth of things, as Bildad has seen them.

Eliphaz has gleaned his supposed divine wisdom from a fabulous vision that he had of a shadowy presence (Job 4:12-21), wisdom that taught him that no mortal can be righteous in God’s presence, no human being pure before the Maker of all (Job 4:17). This faux wisdom suggests that there is little need for any human being to do what is right or good, since God apparently never sees such behaviors, having made all humans impure and unrighteous. This grand vision only adds to the ridiculousness of the fool, Eliphaz. Bildad, on the other hand, gains his nasty knowledge of God’s actions from the tenets of ancient wisdom (Job 8:8-19). He has read and absorbed the proverbs of the past, and from them has learned the following truths: “Look! God will not reject a truthful (tam, again) person, nor take the hand of evildoers. God will yet fill your mouth with laughter, your lips with shouts of joy…and the tent of the wicked will be no more” (Job 8:20-22). Of course, Bildad has already judged Job to be sinner, and has said that God will never reject a tam, an upright/perfect person, exactly who Job is in fact. But the problem is that God has rejected a tam, and that tam is Job.

And Job replies both to Eliphaz and to Bildad in a long speech of chapters 9-10. In Job 9, he works himself up to a frenzy of confusion and fury, fully convinced that he is an innocent man, attacked by friends and God for no reason at all. He concludes with what may be one of the Bible’s most astonishing proclamations. “I am blameless (tam); I do not recognize my life; I reject my life! It is all the same; that is why I conclude that God destroys both righteous (tam) and wicked. When disaster brings death, God mocks the terrors of the innocent. The earth is handed over to the wicked; God covers the judges’ faces; if it is not God, then who is it” (Job 9:20-24)? In Job’s reasoning, Eliphaz’s wisdom that no one may be either righteous or pure in the sight of God turns into the belief that God cares not at all for any human being; in fact, when death occurs God enjoys the tragedy, mocking at the innocent, denying any justice to the earth. Bildad’s announcement that God killed Job’s children because of their wickedness Job reverses into the belief that God may have done it, but for no reason of righteousness or unrighteousness, merely for the fun of watching the children die. It is a frightening idea that Job has spoken, and gives the lie to those who say “Job almost blasphemes” in his ravings against God. I must disagree; Job blasphemes often and directly against the God he has been taught, the one he thought he knew. It just might be that that God, the God of the friends, is worthy of blasphemy, fully subject to attack. That may be one of the author’s chief concerns, namely to clear the world of such a God.

After that amazing and deeply troubled assault by Job on God, Zophar, the third friend, does not hold back in his furious reply. “Should a vast store of words go unanswered; should a lippy one be called righteous? Should your babel shut others up; when you mock, shall none cry, ‘Shame’? You say, ‘My teaching is pure, and I am clean in your eyes.’ If only God would speak, open divine lips with you…Know then that Eloah exacts from you less than your guilt deserves” (Job 11:2-6)! According to Zophar, God is too lenient with Job, demanding less than his mountain of evil has incurred. What does he imagine God will add to the punishment; the removal of his filthy robe and broken piece of pottery? Like his two friends Zophar has no doubt that Job is receiving from God precisely what he deserves, and the certainty of that has been revealed to Zophar through meditation on the “deep things of God, the limits of Shaddai” (Job 11:7). While Eliphaz received a vision, and Bildad read widely in the wisdom of the ages, Zophar contemplates the depths and breadth of the infinite God. Yet, all three come to the same conclusion: Job is evil and is getting God’s righteous judgment. God is only just, and that justice requires that the sinner lose all and end in agony on the ashy heap. Thus is the God of reward and punishment once again vindicated, God’s reputation secure as strict judge of all human action.

In the succeeding chapters, during the final two cycles of speeches (Job 15-26), the friends change their positions not at all; they began by hating Job and they end by hating him. Meanwhile, Job does change, from wishing never to have been born, to desiring his death, to demanding that the friends listen to his anguish, to rejecting their constant attacks against him, and finally turning to God as the source of his pain and torment. It has become clear that the tale will only be concluded by a visit from God, but that visit may hold its own surprises as we will see in our final installment 6. Next time, in essay 5, we will examine one special concern that the story addresses, a remarkable concern about an unnamed third party whom Job imagines might solve his dilemma with this angry God. And we will see how the story leads up to the appearance of YHWH to Job in a great storm.

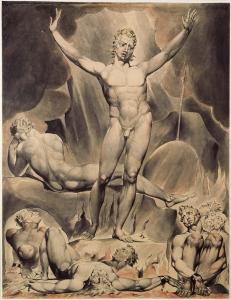

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)