Of the discussions of the contested relationships between the church and the state there truly is no end, and I think that is exactly right. The existence of these two powers in every society must by necessity serve as the source of a healthy and vigorous interaction. This is so because the two represent the most prominent institutions in the culture no matter where that culture be found. By “church,” I mean those institutions that concern themselves with matters religious, be they mosque, church, temple, synagogue, or studios of various sorts, any place that purports to represent a power or existence that transcends the normal workings of civil society, God, Allah, YHWH, a transcendent ethic of whatever variety. By “state,” I mean the orders of society, however constituted: democratic, dictatorial, parliamentary, republican, among other permutations. Just how these two complex organizational structures confront, aid, and warily debate one another is the essence of the matter. We in the USA at this juncture in our history are particularly engaged in that wary debate, however confused the two sides may be concerning the actual bases of that debate.

Of the discussions of the contested relationships between the church and the state there truly is no end, and I think that is exactly right. The existence of these two powers in every society must by necessity serve as the source of a healthy and vigorous interaction. This is so because the two represent the most prominent institutions in the culture no matter where that culture be found. By “church,” I mean those institutions that concern themselves with matters religious, be they mosque, church, temple, synagogue, or studios of various sorts, any place that purports to represent a power or existence that transcends the normal workings of civil society, God, Allah, YHWH, a transcendent ethic of whatever variety. By “state,” I mean the orders of society, however constituted: democratic, dictatorial, parliamentary, republican, among other permutations. Just how these two complex organizational structures confront, aid, and warily debate one another is the essence of the matter. We in the USA at this juncture in our history are particularly engaged in that wary debate, however confused the two sides may be concerning the actual bases of that debate.

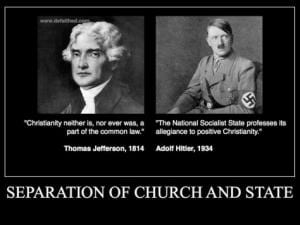

The US has enshrined in the very first amendment to its central document, the Constitution, the uniquely clear notion that ““Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” This 1787 statement, in the main the product of James Madison, was intended to make it crystal clear that in the newly founded USA, there was never to be any “established religion,” that is a religion that had been “established” by any authority, as superior to any other religion. Hence, for now 233 years, our most important recognized document has stated clearly that no religion— Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism—may be viewed as in any way established as “the” region of the country. Note that not only may congress not establish any religion as the religion of the US, but neither can it “prohibit the free exercise” of any other religion. Here we find the very foundation that the founders of the US hoped would represent their conviction of the need for the complete separation of church from state. Thomas Jefferson in 1814 went so far as to claim that “Christianity is, nor ever was, a part of the common law.” That is, Christianity, according to one of the architects of the American understanding of society, was in no way considered to be anything other than one possible religion among others. But because that is historical fact, the relationship between religion and state continued to be fraught with controversy.

This is so because the overwhelming majority religion of the country has been, and continues to be, Christianity. And Christianity, like most religious traditions, makes universal claims concerning its validity and superiority to other religious traditions. “Refusal to accept Christ,” however that phrase may be understood—and it has a myriad possible meanings depending on the branch of Christianity one espouses—leads one to be on the outside of Christian belief and practice, at least according to some Christians. (I hasten to add that I am not one of their number.) Still, if Christians express the conviction that their religious expression is universal, and hence by definition, superior to any other, the Christian majority can quite easily decide that their influence on society and the state is crucial to the proper understanding of what it means to be an American. Why else have uniquely Christian constructions of morality—abortion and same-sex marriage being two recently prominent bones of contention—dominated legislatures and courts for the previous 50 years? To be sure, there are those among us Christians (again I being one) who understand both abortion and same-sex marriage quite differently than many other Christians, and within the bounds of our Christian convictions, but that does not contest that fact that Christian beliefs here intrude on the workings of the state. If the state is to have no truck with any religion, and cannot in any way establish any one of them, then just why are issues of Christian morality so contested in the activities of the state?

Let me inject a small personal example of the problem as I see it. I have performed many weddings in the course of my 50-year ministry, and after each one of those, I am presented with a marriage license, a government-issued document, that I, as a clergyperson, must sign if the wedding is to be recognized in law by the state. Is this not a clear entanglement of church and state? I well realize that this has become far looser in the course of time; well nigh anyone may perform weddings now. My own musician son, with no theological training whatever, and who classes himself as an atheist, has performed several weddings for friends and acquaintances. Those weddings are no less legal today than the ones I have led, but still up until very recently that license had to have the scrawled signature of an ordained clergyperson to sustain its legality. The supposed wall erected between the church and the state is at best a very low wall; it might better be termed a chain link fence with gates readily available for opening both ways.

Another odd example. When I was active as a clergyperson, either in a local church or as a member of a theological faculty, I was entitled to an untaxed housing allowance for purposes of my yearly income tax form. Like members of the military, that meant that I could remove from my tax burden the costs of my housing expenses; in fact in certain instances where housing costs were quite high I might have argued that my entire salary (!) could have been designated as housing allowance, and thus was non- taxable under US tax law. (Please note that I never made that claim, but I am aware of some clergy who have done so.). This portion of the tax code is a fallout from the fact that houses of worship have long been untaxed in the country. When certain “ministries” of certain places of worship bleed over into rather more secular areas (e.g. housing projects, restaurants, various shops), the taxable areas become decidedly gray. All of this is to say that the interpenetration of church with state is hardly as clear and certain as Jefferson may have hoped.

So now we have the president of the US, Donald Trump, holding a Christian Bible aloft in front of a Christian Church, silently proclaiming, one supposes, that that Bible provides for him the “divine” authority to act in ways he determines his office allows him to act. His action just prior to his lifting of that Bible was to clear a street of peaceful demonstrators by very violent means—flash grenades, tear gas, police shields and batons—in order that that Bible might appear in the president’s right hand to announce, however wordlessly, that this particular book gives him the right to act however he wishes. It was a classic and terrifying display of the total misunderstanding of what the First Amendment was intended to prevent, namely the overt establishment of the authority of the Christian Bible over all other religious authorities, and to reject, violently and decisively, the right of peaceful protest to address grievances in the society, in this case the murder of many African-American citizens at the hands of vested police authorities. The president in one appalling photo trod upon two of the most basic rights enshrined in the founding document that his 2016 inauguration said that he had “sworn to preserve and protect.” That photo proclaimed that Christianity was in fact established in the US, and that peaceful protest was subject to the whims of the president to accept or to reject. That photo was the epitome of the act of a dictator, not the president of the USA.

Church and state always sit as uneasy adversaries or potential partners in the organization of any country. The French Revolution outlawed religion as dangerous to the state; British history demonstrated the vastly destructive results of establishing one religion over another, whether Catholic or Protestant, state control of either over decades leading to anathemas and stake burnings aplenty. The founders of the US tried to learn from both of these extreme European examples, attempting to clarify that no religion may be established over another, so that the state may live free from the dogmas of any one of them. The struggle continues, and is not likely to end, for it is in the very nature of certain religions that the state must bow to the church, while certain members of the state continue to refuse to allow any church to dictate to them how the society should be ordered. Surely this contested relationship makes living in the 21st century USA fascinating and frustrating at the very same time.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)