Today’s lectionary text is among the most famous in the all of the scripture. It is so well known that it has become a cliche in the contemporary western world. No upset victory in sports or politics is announced without reference to the ancient win by the shepherd boy David over the seasoned and massive Philistine giant Goliath. “Dewey Defeats Truman” became an iconic New York Times headline, famous because the opposite had in fact happened; the underdog Truman had in fact won the 1948 presidential election, and his victory was regularly termed a real “David defeats Goliath” event. When Super Bowl III, that pitted the heavily favored Baltimore Colts against the upstart New York Jets, and their flamboyant quarterback, Joe Namath, the astounding Jet win was once again called a victory of David over Goliath. It is the surprise of the winner that calls forth the cliche. I wish to demonstrate in this essay that the cliche is not based in a careful reading of the biblical text. David knew immediately that he could defeat the giant when he first saw him, and the author makes that plain to those who have eyes to see.

Today’s lectionary text is among the most famous in the all of the scripture. It is so well known that it has become a cliche in the contemporary western world. No upset victory in sports or politics is announced without reference to the ancient win by the shepherd boy David over the seasoned and massive Philistine giant Goliath. “Dewey Defeats Truman” became an iconic New York Times headline, famous because the opposite had in fact happened; the underdog Truman had in fact won the 1948 presidential election, and his victory was regularly termed a real “David defeats Goliath” event. When Super Bowl III, that pitted the heavily favored Baltimore Colts against the upstart New York Jets, and their flamboyant quarterback, Joe Namath, the astounding Jet win was once again called a victory of David over Goliath. It is the surprise of the winner that calls forth the cliche. I wish to demonstrate in this essay that the cliche is not based in a careful reading of the biblical text. David knew immediately that he could defeat the giant when he first saw him, and the author makes that plain to those who have eyes to see.

The keys to understanding the remarkable scene more fully may be found in three significant places in the narrative. The first occurs at the beginning when we are introduced to the champion warrior of the Philistines, Goliath of Gath. The narrator gives the reader one of the longest and most detailed descriptions of any human figure in the Hebrew Bible, as a full 4 verses portray the immense figure. The storyteller spends no time describing the physical features of Goliath’s face, but does give us a rich picture of the man as he is seen by his enemies, the Israelites, gazing at the monster across the valley of Elah. He is preternaturally tall, “six cubits and a span,” we are told (the Greek version of the scene written in the 3rd-2nd century BCE Septuagint apparently does not believe this tally and changes the number 6 to 4, a far more reasonable height). It is commonly thought that the ancient cubit was the distance between one’s elbow and the tip of the middle finger, eventually standardized in Egypt and elsewhere at about 20 inches. A “span” was literally 1/2 a cubit, hence about 10 inches. Thus, Goliath is about 10 1/2 feet tall, according to the story. “He had a bronze helmet on his head,” perhaps something like the ancient portrayals of helmets of antiquity, with a nose piece to protect that part of the face. It is difficult to determine just when the story was written, but it is unlikely to be older in formulation than the time when iron weapons were in wide use. Bronze became, during the Iron Age, a more ceremonial metal than one used in actual battle. It could well be, then, that Goliath puts on his bright bronze gear rather than his actual battle gear for show; he perhaps feels little need actually to fight against these pathetic Israelites.

He also appears adorned with chain mail armor covering his chest, armor weighing “five thousand bronze shekels,” perhaps about 125 pounds in modern weight. “He had “greaves of bronze on his legs” (again ceremonial?), something like modern day shin guards, and “a spear of bronze slung between his shoulders.” The spear shaft was “like a weaver’s beam” (some four inches in diameter?), while the “blade of the spear was 600 shekels of iron (maybe 16-20 pounds?). And a more normal sized human servant went in front of him, bearing his gigantic shield, probably completely hidden by its vast size. Goliath by any measure is a formidable, if not impregnable fighting machine, and generations of Bible readers have been dutifully terrified of the portrait drawn by the author.

However, something of that terror may be slightly blunted by the next scene, the second one we need to pay special attention to. Goliath in his mighty splendor strides toward the stream that divides the two warring camps and thunders a challenge to the ranks of Israel. “Why should you come forth to deploy for battle? Am I not the Philistine, and you are Saul’s slaves? Choose you a man and let him come down to me! If he wins the battle against me and strikes me down, we shall be slaves to you, but if I prevail and strike him down, you will be slaves to us and serve us…Give me a man and let us battle together” (1 Sam.17:8-10)! “Mano a Mano,” screams Goliath; let single combat decide the day! It is a powerful speech, uttered with ferocity, striking horror in all who hear it. The result is “dismay and terror” in Saul and the entire army (1 Sam.17:11). Goliath’s first challenge was indeed a terrible one, but note that this same challenge is uttered by the giant “for forty days, both “morning and evening” (1 Sam.17:16). Would not Goliath’s speech lose something of its force after it was spoken quite literally 80 times? One might picture the Israelite camp reckoning its daily routines, based on still another redundant speech by Goliath!

This numbing routine is finally broken when the boy David, who has been provisioning his brothers all this time, happens to come to the camp while Goliath is again issuing his challenge (time 81?). The speech may be the same—every Israelite may by this time be able to repeat the giant’s words along with him—but what is different is the fact that David hears the speech and sees the giant standing near the stream. David takes one look at Goliath and knows he can defeat him. How?

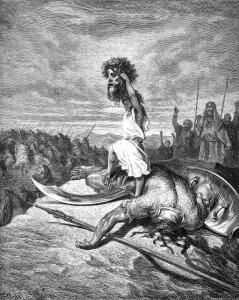

The answer may be found in the third scene that is crucial for a full understanding. David, after asking three times what one may receive by defeating the giant, heads to the confrontation with two objects, one visible and one hidden. The first is his shepherd’s staff, disdained by Goliath as a “stick.” The other hidden object carries with it Goliath’s doom. It is David’s sling, a weapon he has mastered during those long days watching the foolish sheep in the wilderness, where he claims to have killed both lions and bears while guarding the flock. And though his narrative about his prowess is almost certainly exaggerated for maximum effect (1 Sa.17:34-37), he is clearly an artist with that sling. That is why David knows that his victory is assured. While others have witnessed the massive Goliath as an impregnable warrior, David has seen him quite differently; he is literally a tank without an engine, a slow moving juggernaut of a man, and David has just the instrument to bring him down—a mobile missile launcher.

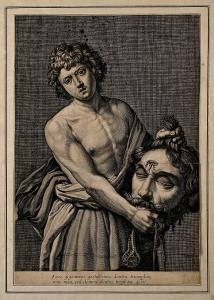

1 Sam.17:48 makes that view certain. Here is a very literal translation of the verse: “So it happened that the Philistine arose (was he crouched or seated?), walked, drew near in order to approach David, while David hastened and rushed toward the line to meet the Philistine.” It takes Goliath four verbs even to get close to his opponent, while David in two insistent verbs ran toward the giant, of course keeping out of reach of that giant spear, but getting close enough for a clean shot with his sling. The battle is over quickly; Goliath is soon face down in the stream and David is cutting off the giant’s head with Goliath’s own sword. David’s victory was certain as soon as he laid eyes on Goliath and assessed the situation carefully and logically. The cliche about “little guy unexpectedly beating big guy” is not rooted in this carefully written text.

What then do we make of the scene? There can be little doubt that David feels that YHWH is with him in the struggle, but YHWH is not the only one who fights the battle. David is clever, resourceful, and confident, knowing full well that the day will be his, and that Goliath will be his meal ticket to greatness. It is this complex David—man of God, man of David—that we will meet and assess in all future tales of the man. Here in the confrontation with Goliath that man is first clearly revealed to us. No romantic notion of “handsome David” or “pious David” or “clever David” and even later “murderous and adulterous David” can do full justice to that complex man. But of course, no one of us may be judged in one simple way either. In that we are all rather like this ancient and enigmatic second king of Israel, are we not?

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)