It is more than a pity, rather more an outrage, that this lovely and delightful series of poems from an unknown author and an unknown time, has long been known as “Song of Solomon.” The third king of Israel, born and dead in the 10th century BCE, was indeed famous for his vast harem, comprising “seven hundred princesses and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11:3); the sheer number of these women, among whom, we are told were “many foreign women” (1 Kings 11:1) whom the king loved. And the highly critical and censorious editor of the book of Kings adds the vituperative note: “when Solomon was old, his wives turned away his heart after other gods, and his heart was not true to YHWH his God, as was the heart of his father David” (1 Kings 11:4). After having read the lengthy narrative about David, concluded with his involvement of his heir Solomon in several revengeful murderous schemes, the claim that David’s heart was true to YHWH is dubious at best, and it could well be said that Solomon hardly needed foreign women to turn his heart away from YHWH, since he seemed quite capable of making that turn on his own.

It is more than a pity, rather more an outrage, that this lovely and delightful series of poems from an unknown author and an unknown time, has long been known as “Song of Solomon.” The third king of Israel, born and dead in the 10th century BCE, was indeed famous for his vast harem, comprising “seven hundred princesses and three hundred concubines” (1 Kings 11:3); the sheer number of these women, among whom, we are told were “many foreign women” (1 Kings 11:1) whom the king loved. And the highly critical and censorious editor of the book of Kings adds the vituperative note: “when Solomon was old, his wives turned away his heart after other gods, and his heart was not true to YHWH his God, as was the heart of his father David” (1 Kings 11:4). After having read the lengthy narrative about David, concluded with his involvement of his heir Solomon in several revengeful murderous schemes, the claim that David’s heart was true to YHWH is dubious at best, and it could well be said that Solomon hardly needed foreign women to turn his heart away from YHWH, since he seemed quite capable of making that turn on his own.

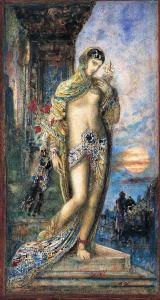

That is a too long of saying that Solomon has nothing to do with the composition of these superb poems. They come from another era, to be sure, and their interest is hardly the display of King Solomon’s sexual prowess, let alone his ardent desires for multiple female partners. The poems are in fact brilliant paeans to sensuality and sexual love between a man and a woman, and their placement in the canon of our scripture should be a great literary offering to those who are fully aware that human sexuality is one of God’s best gifts to us, and that the exercise of that gift is completely and totally within the sacred life of the most pious and deeply religious people. Of course, that has not been the way that this book has been received in communities of faith. It remains a sort of outlier to the canon of scripture, a book nearly forgotten or avoided when we open our Bibles. This is a tragedy, I think, because it provides for us a tantalizing glimpse of just how delightful and fulfilling men and women may find their God-given bodies to be. (Note: same sex couples may find equal pleasure in the rich poetry of sexual love, though the poems are clearly written with males and females in view.)

As I noted above, the title of the book that has become traditional leads us in the wrong direction. In Hebrew the title may be translated as “The Most Beautiful Song,” expressing one way that the language indicates the superlative. “Song of Songs” may be woodenly literal, but it is more than that; it is nothing less than the most beautiful of songs. And it is the most beautiful of songs precisely because it hymns one of life’s most beautiful and gracious acts: the sexual relationship between a woman and a man. The poet tries in every way possible to portray the longing, the deep desire, the languorous coupling between the two persons in order to model for his readers the profound panoply of emotions and actions that surround the sensual acts of love. One can hardly contain the delights that such lines as Song 5:2-4 provide, when in a dream the anxious woman recounts how she sees the actions of love toward her that her lover has and will offer:

“Listen! My beloved is knocking.

‘Open to me, my sister, my love,

My dove, my perfect one;

For my head is wet with dew,

My locks with drops of night.’

I had put off my clothes;

How could I put them on again?

I had bathed my feet;

How could I soil them?

My beloved thrust his hand into the opening,

And my inner being yearned for him.

I arose to open to my beloved,

And my hands dripped with myrrh,

My fingers with liquid myrrh,

Upon the handles of the bolt.”

The titillating double meanings of “open,” “opening,” and “bolt” are fully intended; she pictures the man entering her chamber but at the same time entering her.

Given such lines, and there are many just like them, it is hardly surprising that early commentators were, if not shocked by such obvious sexuality, had serious misgivings about such language. We of course remember well how the Christian communities rather quickly turned away from the traditional lives of family toward celibacy and isolation as the finer expressions of religious devotion. For at least 1000 years, unmarried men were the leaders of all Christian churches. Such men would certainly have been troubled by the language they found in the Song. Hence, many of them began to read the poems with fanciful allegory in mind. The beauty of allegory is that one is only limited by imagination when reading troubling texts. So, for example Origin, that important early commentator on the Bible, saw in the Song an allegory of the relationship between Christ and his church, employing the man and the woman as symbols only of that great truth. In that, he borrowed the earlier rabbinic notion that the Song allegorically demonstrated the vast love between YHWH and Israel, once again using the woman and the man as the necessary vehicles for that truth.

When later readers, like Gregory the Great, read the poems, he found increasingly fantastic allegorical truths locked in the sensual words: the woman’s navel, depicted so lovingly at Song 7:2 was in reality a baptismal bowl while her two breasts, described as “two fawns” at 7:3, were in allegory the two covenants of the Old and New Testaments. The Song was for centuries the most read and commented upon book of the Hebrew Bible, eliciting a vast array of extravagant and illusory meanings that have hardly stood the test of time, for which we may all be grateful!

I suggest two important ways that the Most Beautiful Song may serve our communities in the 21st century. First, as Phyllis Trible first noted in 1974, the poems quite wonderfully and quite surprisingly picture the man and the woman as equal in their desire and ardor for one another. In the clearly patriarchal world of the Hebrew Bible it is nothing less than astonishing to encounter a book where men and woman are in crucially important respects equal in stature in the art of love. The woman desires the man, and he in turn desires her; both are so portrayed in the Song. In our modern world, where the patriarchy is alive and all too well, it is salutary to discover a book of the Bible that celebrates male-female equality.

Second, there is a line that has been egregiously mistranslated for far too long, and I would like to offer a better reading for our particular moment in US America. Older readings read Song 1:5 as “I am black but beautiful,” suggesting to many generations of Bible readers that though the woman is black she is somehow beautiful anyway, an apparent anomaly since it was for ages believed by many white people that black people could simply not be beautiful. Fortunately, the NRSV now reads, along with many translations: “I am black and beautiful,” restoring both the Hebrew original and the obvious notion that many black people are in fact beautiful, just as many persons of other colors may also be.

Today’s chosen text from the Song unfortunately does not include any of the sensual and subtle language I demonstrated above. It does include the well-known line, often set to music: “Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away; for now the winter is past, the rain is over and gone. The flowers appear on the earth, and the time of singing has come..” (Song 2:11-12). Pleasant enough lines, I suppose, but far from the resonant sensuality of so much of the poet’s lyrics. I have long suggested that the Song could serve well as the basis for a retreat setting, exploring the intimate relationships in the context of church life between couples, whether gay or straight. And in a world where sexual confusion and exploitation are woven into the fabric of our modern lives, using the Song as an announcement that sexual love is a significant part of God’s desire for us could be salutary for many people in need of a sacred word about such a crucial and contested area of our lives together. The Song is ready for our use; I urge you to take it up and release its unique treasures for your community.

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)