The story of David that we have been reading now comes to the place that offers by far the most memorable and the most deplorable narrative. 2 Sam.10 suggests that David’s long struggle to defeat his many enemies surrounding his expanding empire has been primarily successful, the penultimate foes, the Arameans, being forced to “make peace with Israel and become subject to them” (2 Sam.10:19). Only the Ammonites remain as a thorn in David’s side, and he is about to dispatch his army under the command of the redoubtable Joab to subdue them and to gain a genuine peace for the nation. In short, the long road to calm and peace for his people has been traversed, and David may look forward to a period of ease and comfort as the beloved king of Israel.

The story of David that we have been reading now comes to the place that offers by far the most memorable and the most deplorable narrative. 2 Sam.10 suggests that David’s long struggle to defeat his many enemies surrounding his expanding empire has been primarily successful, the penultimate foes, the Arameans, being forced to “make peace with Israel and become subject to them” (2 Sam.10:19). Only the Ammonites remain as a thorn in David’s side, and he is about to dispatch his army under the command of the redoubtable Joab to subdue them and to gain a genuine peace for the nation. In short, the long road to calm and peace for his people has been traversed, and David may look forward to a period of ease and comfort as the beloved king of Israel.

The nation encompasses the largest territory it was to have in its long history—about 100 miles north to south, and from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River and beyond—was in the middle of David’s reign the area of his empire. Of course, by Middle Eastern Empire standards, it was hardly significant, but after arising out of a small section of the hill country of the land under Saul, perhaps 50 years earlier, its extent could be seen as quite important, enough to earn the gaze of some nations round about. It is at this place of ease that David commits the greatest blunder of his life, a rash and unthinking mistake that leads to further monstrous consequences that usher in the decline and eventual fall of Israel’s most renowned leader.

It all began so innocently. But with an innocence fraught with danger. “It happened at the turn of the year, the time when kings go out to battle, that David sent Joab and his servants with him and all Israel, and they ravaged the Ammonites and besieged Rabbah. And David remained in Jerusalem” (2 Sam.11:1) Why the great King David stays in Jerusalem, when it is precisely the “time when kings go to battle” is the mystery of this text. Not only was David “staying” in Jerusalem, but more literally, he was “sitting” there, far removed from his kingly duty as leader of troops, separated by inaction and the sedentary life of a king who could just no longer be bothered. In short, David is ripe for a private adventure; all the men of the city are gone to fight, and the metropolis is quiet and hushed. “At eventide, (in the late afternoon), David got up from his bed (after a delicious afternoon nap) and took a walk on the roof of the palace, and he saw from the roof a woman bathing, and the woman was very beautiful” (2 Sam.11:2). Who is this, David wants to know, and he is informed that she is Bathsheba, “daughter of Eliam wife of Uriah the Hittite.” “So David sent messengers and fetched her and she came to him, and he slept with her, she having just cleansed herself of her impurity, and she returned home” (2 Sam.11:4).

The account of the adultery is matter of fact, spare to the point of near invisibility. The fact of who the woman is—daughter and wife of one of David’s mercenary soldiers—has no bearing on the lust he feels for her. He “sends” and “fetches,” she “comes,” and he “sleeps “with her. There is no dialogue, no romantic tryst, no flowers or dainties, no lengthy introductions, no playful prelude. He is king, and he may do as he pleases. Though he has numerous wives and a palace full of children, Bathsheba is desired, and the king’s desires are to be fulfilled. Besides, she is beautiful, and she is ritually pure, suggesting both that any pregnancy cannot be the result of Uriah’s sexual activity, and promising that she is relatively safe from becoming pregnant by anyone else. Nevertheless, she becomes pregnant, and now David must act.

He has any number of choices he might make. He is king, and nobody may question his actions! And what is one more woman added to the expanding harem? So what if she is with child? One more of the king’s children is not a matter of any real concern. Are there not nurses enough to provide care to the royal brood? Yet, despite all that, David acts as if he had done something worthy of hiddenness, a deed that should be kept out of the public eye. So he sends for Uriah, hoping to lure the old soldier into his house to be with his nubile wife, thus making the baby potentially his. But Uriah will not go down to his house, for unlike his king he is a man of honor and dignity; he will not “eat and drink and sleep with” his wife, as long as his valiant men are fighting and dying at the walls of Amman. So David ups the ante. He writes a letter to Joab, demanding that his faithful henchman place Uriah in the thick of the battle to ensure that he be killed. His instructions are ridiculous! “Put Uriah in the place of the fiercest fighting and draw back, so that he will be struck down and die” (2 Sam.11:15). The king is hardly thinking clearly with these instructions. If Uriah goes up to the fight, and at a certain signal, all other soldiers draw back, leaving Uriah alone, will it not bring anxious whispers, if not outright rage, from the men who must then watch the lonely doom of one of their leaders? So Joab covers the stupid plan by including several innocent warriors at the attack point so that they too may die, along with Uriah. That way, no one will be the wiser, and David will get off Scott-free.

The plan works, Uriah and several of his men are killed at the wall of Amman, and when David is informed of the deaths, he mutters a truly repulsive reply. “Let this thing not seem evil in your eyes, for the sword devours sometimes one way and sometimes another. Fight all the more fiercely against the city and destroy it. And encourage him (Joab)” (2 Sam.11:25). Nice work, old boy, says the reprobate David; that was handled deftly indeed! Then suddenly and quite surprisingly, the narrator enters the tale and pronounces a scathing judgment on the whole mess: “the thing that David had done was evil in the eyes of YHWH” (2 Sam.11:27). And so it surely was.

After this appalling series of acts on the part of the king of Israel, his life becomes a catalogue of disasters, both public and private, culminating in his compact with his heir, Solomon, to murder a helpless old enemy for a slight David suffered decades before. The last words of David are a contract for the killing of the elderly Shemei (1 Kings 2:8-9).

These are sordid tales, but they are the truth about the man David, remembered as the model king in the history of Israel. Why tell such stories about such a figure? The simple answer is that David is human, as we are, that David is not in the slightest way god-like, that David is never to be thought as superior to any of us in any way. He is YHWH’s choice for king, but he is decidedly a weak and pale human being, no more and no less. To tell these stories so brilliantly, so vividly, is to keep that picture alive as long as there are readers to read them and to take them seriously.

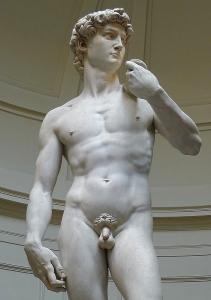

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)