This year in the lectionary, the collectors offer to the preacher in the season of Easter a short series based on the book of Revelation. From the second Sunday of Easter through the seventh, up to the Day of Pentecost, the preacher may choose passages from the Revelation of St. John, the Divine, from Rev.1 right through to the end in chapter 22. Since the Hebrew Bible is traditionally avoided during this season, save the Psalms, (for reasons that have always been opaque to me, if not downright pernicious), while texts from the Acts of the Apostles are offered by way of substitute, instead of the usual epistle alternative to the Gospel and the Hebrew Bible, we find the book of Revelation. This fact is one preachers need to take advantage of.

This year in the lectionary, the collectors offer to the preacher in the season of Easter a short series based on the book of Revelation. From the second Sunday of Easter through the seventh, up to the Day of Pentecost, the preacher may choose passages from the Revelation of St. John, the Divine, from Rev.1 right through to the end in chapter 22. Since the Hebrew Bible is traditionally avoided during this season, save the Psalms, (for reasons that have always been opaque to me, if not downright pernicious), while texts from the Acts of the Apostles are offered by way of substitute, instead of the usual epistle alternative to the Gospel and the Hebrew Bible, we find the book of Revelation. This fact is one preachers need to take advantage of.

No biblical book causes more consternation, makes unwary readers more queasy, serves as fodder for prophetic mountebanks seeking a quick buck, than this very peculiar book that lurks at the end of the New Testament. Whenever I am asked to come to a church and offer a Bible study of one sort or another, Revelation is always high on the list of desires, primarily because few church folk know what to do with the thing! And by “church folk” I also mean more than a few pastors. In their seminary years, Revelation is regularly addressed at the end of the semester of introductory New Testament studies, and is given perhaps one class period, or at most two, as the semester winds down. A few general comments about Apocalyptic literature, some fun and games with the number of the beast, and a fig thrown at the final chapters that do make a lovely end to the term with their talk of healing leaves and the end of weeping and crying at last, not the weeping and crying of beleaguered students only, but all weeping and crying of a world too full of both. And there you have Revelation! However, when the several parishioners come to the pastor and inquire about what this odd writing is about, the pastor may be in no position to offer a satisfactory explanation.

So, I propose in the next six weeks of the Easter season to take a closer look at this book, and see whether it may provide more valuable material for the preacher than first meets the jaundiced eye. But first a bit of historical commentary will prove important. As I have studied this book, and I have spent a good deal of time with it, I first learned that it was probably composed during the reign of the Roman emperor Domitian, who was on the throne from 81-96CE. During his reign, the empire was wracked with any number of plots against Domitian who was nearly universally detested by the senate and held in considerable contempt by the people. When he was assassinated by the preferred Roman knife, there were few who mourned his brutal passing. Like many rulers both before and after him, he fancied himself some sort of divinity and demanded that his image be worshipped in various parts of the empire. Failure to do so could result in severe penalties, including imprisonment or even death. Against that backdrop, John writes his Revelation apparently from the Roman prison compound on the island of Patmos, a small volcanic rock off the coast of Asia Minor. According to Rev.1:9, John has been sent to Patmos “because of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.” This phrase has long been taken to mean that John has been preaching Christianity in the cities of the empire, and for that seditious act he has been arrested and confined on Patmos. There is little indication that Domitian’s rejection of the emerging Christian cult was more severe than that of, for example, Nero, but it was surely harsh enough to create among the Christians a feeling of dread and fear. It is to those feelings of dread and fear that John writes his book.

The message of the book of Revelation is really quite simple, notwithstanding the very complex ways it employs to express its truth: God wins, he says, in very colorful language and vividly strange images. Whoever happens to be the emperor of the empire of Rome is not the real power in the world; that power is God’s and God’s alone. It is up to John’s hearers and readers to understand and accept that fact and live their lives accordingly, even if such living leads them to terrible persecution and even death. If that reality is kept clearly in the forefront of one’s mind, the wild language of the book may be seen for what it really is, namely a style of writing, well known in its time, but a style that has become over the centuries hard to penetrate.

Whether or not the book of Revelation is a classic example of Apocalyptic writing or whether it is merely a book replete with images and language that reflect such a style is not that important for the preacher. Clearly, John, whoever he was (he is plainly not the author of the Gospel of John, for his Greek is too often vague and ill-formed, unlike the Gospel writer’s superb, high-flown Greek), knew his Hebrew Bible and most especially the book of Daniel, many of whose images he borrows and uses for his own purposes. I have counted over 500 overt and more subtle references to Hebrew Bible passages, so I would call the book nothing less than a midrash on parts of the first testament. But John takes this material and molds and shapes it in fantastic and illuminative ways, fashioning a book that has attracted artists, both musical and literary, for all the centuries since his writing.

On the island of Patmos, one finds a cave of the revelation wherein John is reputed to have encountered the divine one, who gave to him the words of his book. It is a beautiful, holy, and strange place all right, but I doubt it is at all what visitors are told it is. John’s composition has the hallmark of careful construction, not immediate divine dictation. It is a sermon in words and pictures designed to speak truth to the power of the Romans, and to shore up the flagging faith of those early Christian believers who faced an uncertain and dangerous future in the empire.

The small portion from chapter 1 assigned for this day gives to us some indication of what we are about to read. It is first important to note that John loves the play of numbers, especially the numerals 3 and 7. Both of these numbers by late in the first century had become indicators of special divine intention. The emerging idea of a Trinity will soon cement the first number in every Christian’s consciousness, while the latter number has its most ancient origins in the ubiquitous days of the week, as found in the first chapter of Genesis. In Rev.1:4-8 we find any number of threes: God is referred to as the one “who is and who was and who is to come,” nicely summarizing the universal omnipotence and omnipresence of the God who has bid John to write his book. In addition, Jesus Christ is described as “the faithful witness (presumably in his faithfulness even to death), the firstborn of the dead (in his resurrection), and the ruler of the kings of the earth” (Domitian need not apply for the job of emperor—the role is already taken). In the middle of these threes we find “the seven spirits are before the throne” of God.

John continues his number game by saying in his address to the Christ: “To God who loves us and who freed us from our sins by his blood and made us to be a kingdom, priests serving his God and Father.” The attentive reader will hear over and again these holy numbers 3 and 7 throughout the Revelation, markers of the presence and power of God and the Christ. He concludes the section by saying, “I am the Alpha and the Omega (the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, announcing completeness and unity), says the Lord God, who is, and who was, and who is to come.” In this repeated locution John claims something crucial for those struggling for survival in the Roman world: God is, was, and is to come. That is, God is not locked into some holy past of great divine deeds unrepeatable in our own time. Nor is God merely a distant hope, consigned to some pie in the sky heaven, far removed from the painful world we now inhabit. God is now, active, present, standing with us as we work to become God’s children. We need not be afraid, for God is always with us! This is the essence of John’s claims for his own time and for ours; we are not alone, no matter how miserable and terrible our lives appear to be.

As we proceed through the book, we will hear this theme of God’s presence resound again and again, but that presence will take any number of different forms throughout the Revelation. Next week we will hear of a slain lamb, and that image will be one example of how God can show up in ultimately very surprising and peculiar ways.

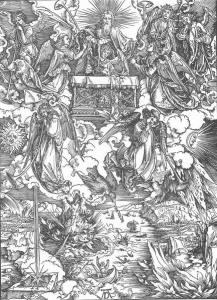

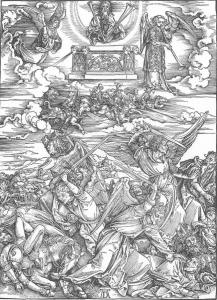

(Images from Wikimedia Commons)