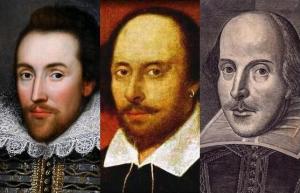

I have loved the plays and poems of William Shakespeare since I first took him seriously during my sophomore year of High School. Our teacher, in actuality a deeper lover of Jane Austen than the bard of Avon, assigned our class the task of presenting snippets of the plays that we performed for one another. My group chose “The Tempest,” and I chose (or was assigned?) the role of Caliban, that crabbed monster, both fish and man, who first lived alone on a magic island but has since been enslaved by the magician Prospero and forced to do hard labor for his master. As I remember it, we did part of Act 2, scene 2, where Caliban first encounters a jesting Trinculo and a drunken Stephano and swears allegiance to them, thinking them to be gods and much more to his liking than the powerful Prospero. I crab-walked out from under our teacher’s desk and tried in my 15- year-old changing voice to make the music of Shakespeare’s poetry sing. I am certain I was a rank failure, but the experience of those words have never left me, now nearly 60 years ago.

I have loved the plays and poems of William Shakespeare since I first took him seriously during my sophomore year of High School. Our teacher, in actuality a deeper lover of Jane Austen than the bard of Avon, assigned our class the task of presenting snippets of the plays that we performed for one another. My group chose “The Tempest,” and I chose (or was assigned?) the role of Caliban, that crabbed monster, both fish and man, who first lived alone on a magic island but has since been enslaved by the magician Prospero and forced to do hard labor for his master. As I remember it, we did part of Act 2, scene 2, where Caliban first encounters a jesting Trinculo and a drunken Stephano and swears allegiance to them, thinking them to be gods and much more to his liking than the powerful Prospero. I crab-walked out from under our teacher’s desk and tried in my 15- year-old changing voice to make the music of Shakespeare’s poetry sing. I am certain I was a rank failure, but the experience of those words have never left me, now nearly 60 years ago.

Of course, the scene we attempted is one of low comedy, ending in farce, as Caliban sips too much of Stephano’s wine, and joins him in drunken subservience, cursing his true master, Prospero, as an evil slave master, and sings of his supposed new- found freedom, as the three lurch off the stage. Later in this glorious play, of course, Shakespeare, now late in his career, demonstrates a full mastery of his poetic art and weaves some of the finest lines in all of English poetry. As Prospero determines to reject his potent magic gifts, he exclaims, “But this rough magic I here abjure, and when I have required some heavenly music—which even now I do—to work mine end upon their senses, that this airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff, bury it certain fathoms in the earth, and deeper than did ever plummet sound I’ll drown my book” (Act 5, scene 1).

And how about the wonders of Act 4, scene 1? “Our revels now are ended. These our actors, as I foretold you, were all spirits, and are melted into air, into thin air, and, like the baseless fabric of this vision, the cloud-capped towers, the gorgeous palaces, the solemn temples, the great globe itself—yea, all which it inherit—shall dissolve, and like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff as dreams are made on, and our little life is rounded with a sleep.” Language of such impressive glory is simply not to be found anywhere else in like concentration.

I have seen performances of these plays in all manner of places. I have been to the birthplace of the man in Stratford and have seen a very modern version of The Merchant of Venice, a period presentation of Love’s Labor’s Lost, and a stark and primitive version of King Lear. I saw in London’s New Globe Theater a rather weak Macbeth, and a very powerful Macbeth at Samuel Grand Park in Dallas at a summer Shakespeare festival. Very recently I saw on the big screen a superb rendition of Hamlet as played by Benedict Cumberbatch, spectacularly, and the Royal Shakespeare Company. These are but a few of my experiences with this great literature; as you can see, I am deeply enamored with this body of plays.

But why should you care at all about a cache of 400-year-old dramas? What on earth may preachers glean from all this Elizabethan poetry? Much of it is difficult to understand, and there perhaps is no worse evening wasted than enduring a poorly presented play by Shakespeare. And I have seen some fairly poor examples; a Dallas Tempest leaps to mind. But the language is sublime over and again. And the ideas enshrined in that language remain fully worthy of the deepest attention. Let me offer only one brief example.

Shakespeare scholars have long argued about the poet’s religious inclinations; was he Catholic in Elizabeth’s Protestant England? Was he safely Protestant? Was he finally not genuinely religious at all? Shakespeare himself never directly answered these questions, but teased us with bits from his plays to whet our appetites and to offer scholars material enough on which to chew. By the evidence of the plays, Shakespeare is neither Catholic, nor Anglican, nor Puritan, perhaps the three options on offer during the late 16th century. God in the plays is not loving parent or avenging Jehovah. The optimistic Shakespeare presents a faith like this: “There’s a divinity that shapes our ends, Roughhew them how we will.” This sounds like a fairly traditional theological view of a God who controls human destiny. But the more pessimistic Shakespeare also can say, “As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods, they kill us for their sport.” Of course, this dark comment is from the mouth of a morbid Macbeth. Or maybe this somewhat less extreme passage mediates between these two sharply opposite views: “There’s special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be now, ‘tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all. Since no man has aught of what he leaves, what is’t to leave betimes?” From the indecisive Hamlet we have these words, and perhaps would expect no different from that person. Still, all ideas are richly Shakespearean, and can lead us to a deeper reflection of the struggle for our own religious beliefs.

Finally for me it is the language itself that draws me back to the plays. As a preacher, whose tools are language, it can help me tremendously to read and reread this master wielder of the language he and I share. To be sure, long quotations of those words can fall on deaf ears that are hardly used to hearing them as in former days. When Phillips Brooks, that grand 19th century Boston orator, peppered his sermons with vast swatches of the Bard’s words, (one sermon of his I read included over 100 lines from the plays), he was declaiming them into the ears of his upper-middle class parishioners whose Sunday evening fun was often to read Shakespeare together as family entertainment. Those days are long past, though that still sounds good to me as a Sunday evening’s fun (yes, I am a snob and a pedant for sure!). I am simply not skilled enough to speak these words in such ways as to be understood easily in our day; I do not have the training and I doubt many of you do either. But to read the words, to watch the plays on film or live, is to revel in the wonders of the English language as it can be found nowhere else.

So I urge you to give the old boy a try, if you have not ever done it, or if your contact with him has been long ago in school. I can only say that he continues even now to enliven and awaken my spirit to the wonders of the word. What more can any preacher ask than that?