Some of my favorite moments in superhero stories are not about the caped characters themselves, but about how other people are inspired to heroics (albeit on a more mortal scale) by them.

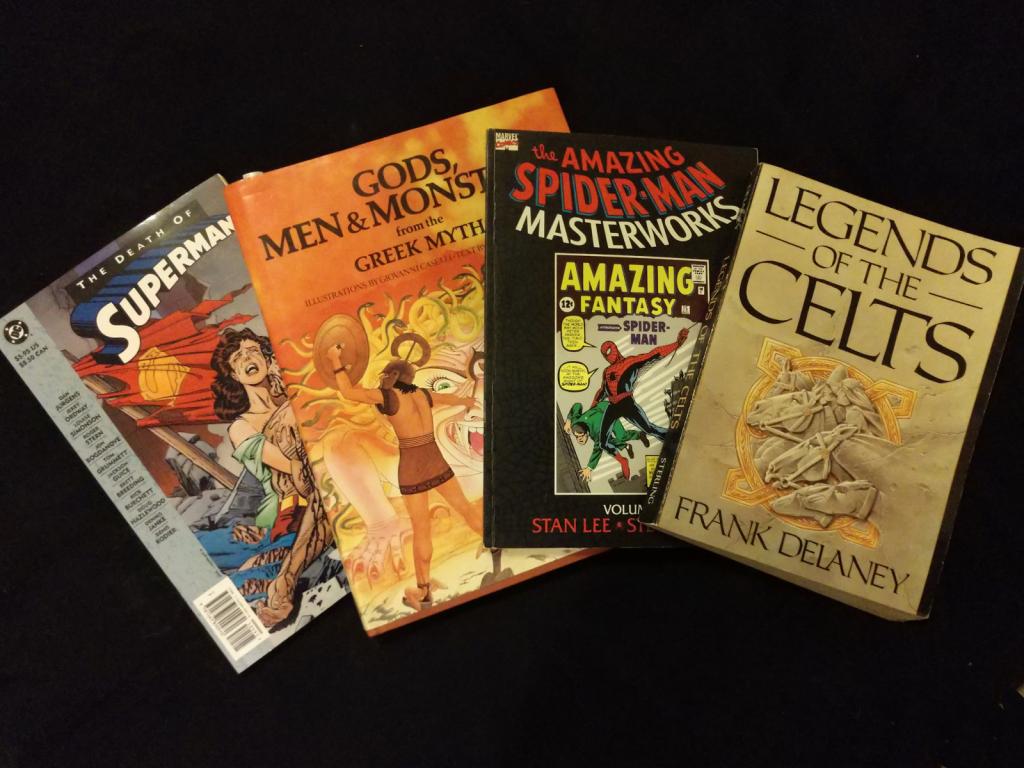

When Superman dies in the classic 1990s comics storyline The Death of Superman (spoiler: he gets better), ordinary guy “Bibbo” Bibbowski takes to the streets in his neighborhood in a Superman t-shirt to clean things up, while super-scientist John Henry Irons fits himself out in powered armor with the famous “S” logo to stop energy-cannon toting street gangs. (Irons eventually develops into a superhero in his own ight, Steel.)

In the 2002 Spider-Man movie starring Tobey Maguire, when Spidey fights the Green Goblin, ordinary New Yorkers join in, throwing bricks and debris. As they rise up against the villain, one yells “You mess with one of us, you mess with all of us!” (A sentiment with extra meaning in New York in the wake of 9/11.)

The exploits of superheroes can inspire the merely mortal citizens of their comic book and movie worlds to be better, braver, and more empathetic. But more than that: their power is such that they can reach out from those fictional universes into ours, and inspire us in measurable ways.

In research published late last year, a team of psychologists examined the effect of “priming” people by exposing them to a picture of Superman. The subjects, who had signed up for a 30 minute research time-slot, were brought into a room that had a small poster of either Supes or a bicycle. (A note on the wall explained away the poster’s presence, saying it was for a different “media images” study.)

The questionnaire they were given was designed to only take 10 minutes. Then they were told they were free to leave, but if they would like to help they could stick around for the rest of their 30 minute slot and participate in an additional pilot study (for no additional credit), and that it would be extremely helpful to the researchers.

Almost 92% of those who were “primed” by seeing Superman volunteered to help, compared to just under 76% of the control group who saw the bicycle poster.

The influence starts at an early age. In a study published in 2016, children age four and six were given a boring task to do, but also given the opportunity to take video game breaks. Some of them were dressed up as characters — including Batman but also such kid-level superheroes as Bob the Builder and Dora the Explorer — and were encouraged to ask themselves “Is Batman (or whoever) working hard?” during the task. The costumed kids displayed the most grit.

(Interestingly, kids who were encouraged to think of themselves in the third person — a classic technique of mental discipline — also showed more grit than whose who encouraged to take a first-person view, but not as much as the cosplayers did.)

Now, I have argued previously that tales of the superheroes are our modern myths; and comics writer and chaos magician Grant Morrison has argued that Superman qualifies as a god:

He was Apollo, the sun god, the unbeatable supreme self, the personal greatness of which we all know we’re capable. He was the righteous inner authority and lover of justice that blazed behind the starched-shirt front of hierarchical conformity.

In other words, then, Superman was the rebirth of our oldest idea: He was a god. His throne topped the peaks of an emergent dime-store Olympus, and, like Zeus, he would disguise himself as a mortal to walk among the common people and stay in touch with their dramas and passions.

[From Morrison’s Supergods : What Masked Vigilantes, Miraculous Mutants, and a Sun God from Smallville Can Teach Us About Being Human, Spiegel & Grau, 2012; p 15-16.]

We come up once again against the question “What is a god[*]?”, but I think we can get broad agreement on two points:

- One does not have to believe that the gods exist independent of human beings to acknowledge them as a real socio-psychological phenomenon.

- When the gods act in the human realm, they rarely perform direct-action miracles; they act through human beings, assisting some and hindering others. Perhaps your tribal gods help your army strike true and mire the feet of the barbarians of the other tribe; but they never seem to just wipe the other tribe off the battlefield with a disintegration ray from the heavens. As the cliche says, the gods help those who help themselves.

([*] I am using the word “god” in the gender-neutral sense it had in Old English, prior to Christianity.)

So a consideration of how heroes and gods as socio-psychological phenomena act through humans is of interest, whether or not one believes they also act in some supernatural manner.

And if superheroes making people a little more kind or possessed of a little more stick-to-itiveness seems like fluffy bunny nonsense, please keep this in mind: on September 11 2001, when the passengers of Flight 93 rebelled against the terrorists who planned to use their plane as a weapon, Superman may have been an inspiration to one of the heroes. Artist and comic historian Arlen Schumer wrote:

…I heard Amy Nacke — the wife of passenger Louis Nacke — tell Dateline how much Louis loved Superman; why, she said, he even had Superman’s “S” shield tattooed on his shoulder for years! I bolted upright from my drawing board when I heard that, because now I knew why it had bothered me so much when those writers claimed superheroes didn’t really matter in real life. “Where were the Superheroes on September 11th?,” they asked? Well, I’ll tell you:

Superman was on United Flight #93.

I believe that Louis Nacke’s love of Superman, emblemized by that tattoo on his shoulder, helped motivate him — even if only “on a small subconscious level” — to garner the courage to confront a terribly hopeless situation. And then to respond heroically, with his fellow passengers, in those desperate moments when action mattered most.

Maybe my conviction is so strong because I know that many of those who face life and death every day — police officers and firefighters — became police officers and firefighters because of superheroes like Superman….

…Superman afforded me, in a more dynamic and accessible form than family or religion could ever really compete with, a specific morality from which to understand the difference between right and wrong and good and evil; and with that, the strength to act on those convictions. Perhaps, on that late summer morning, in the air above Pennsylvania, Superman gave Louis Nacke that strength, too. And in that way, Superman became real.

[From “Text of Arlen Schumer’s Speech Delivered at the Society of Illustrators’ Memorial Exhibition, February 1, 2012” on The Art and Writing of Arlen Schumer, www.arlenschumer.com]

It seems to me that if one wants to worship — “assign worth to” — a god or a hero, the best way to do that is to help do their work.