Our blogging neighbor Julia Penelope recently wrote that using the word “shaman” is “a huge problem within the pagan, witchcraft, and New Age communities, as well as, within academia for many reasons”.

I must disagree.

Julia (if I may presume a first-name basis) says that part of the problem is that “categorizing all indigenous spirituality practices under the same term is that in doing so they are being stripped of their individual identity.” But this sort of thinking removes our ability to make any generalizations.

One might as well argue that we should not use the English word “god” to refer to the religious figures of other cultures — or that we shouldn’t use the word “indigenous” to refer to a variety of Native American nations as well as the Maori of New Zealand, the Yazidis of Iraq, the Ainu of Japan, the Sami of Scandinavia, and the Aboriginal Australians, among others.

Each of these groups has their own unique culture, history, and experiences, but there are common patterns which justify a general category.

The same is true with shamanistic religious practices.

As I wrote in Why Buddha Touched The Earth:

The term “shaman” is of Siberian origin. Out of issues of cultural politics, some object to it being used to describe a diverse array of spiritual traditions – especially Native American traditions. But we lack a better term for the general spiritgual idea being discussed here. Following Joseph Campbell’s usage in his essay “The Symbol without Meaning,” we will use the terms “shaman” and “shamanistic” with the understanding that they are being used in the broadest sense.

Julia asks, “Have you ever wondered why we don’t just call shamans priests? Don’t they act in much the same role? As mediators between humankind and the divine? How do you think Catholic priests would feel if we started calling them Imams and vice versa?” But we do speak of “Shinto priests” or “Buddhist priests” all the time. Because if I said “kannushi” you’d say “What’s a kannushi?” and I’d say “A Shinto priest.” Similarly, a Google Books search shows that “priest” was often used to refer to imams before Islam became familiar to the English speaking world.

“Priest” can be a specific term referring to Catholic religious figures but it also has a general meaning. The same is true of “shaman” — and that general meaning is quite different from “priest”. A shaman and a priest do not fill the same roles.

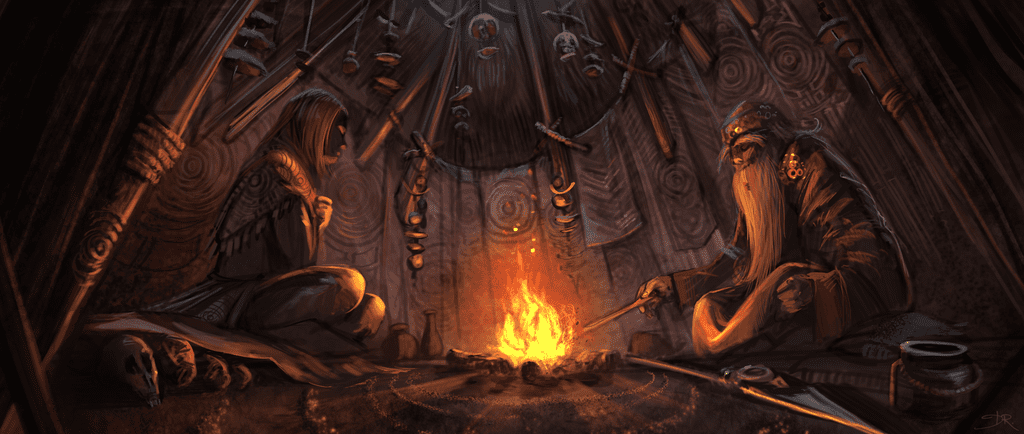

The shaman becomes a shaman via their own personal relation to spirit, their own power — their own personal “mana”, to use another term from one culture used to refer to a more general phenomenon and widely debated by scholars. (That how language works.) In some cases the shaman doesn’t even have a desire to be a shaman, but is selected by the spirits anyway.

Black Elk, the Lakota shaman, provides an exemplar: he was recognized as being on the shaman’s path by his tribe not because he went to seminary or undertook Druid-like training, but because of his near-death vision at the age of nine.

The shaman, as Stanley Krippner notes, is an individual with a socially recognized position — no self-appointment here — which derives from their access to extraordinary sources of information (“spirit world” states of consciousness), and who uses that information for the benefit of the community.

And, as Joseph Campbell wrote, the shaman operates in a less specialized culture where the direct mystical experience is available to all — some sort of “vision quest” experience is widespread. (Again, the language of one specific instance of a general phenomenon becomes a general term for the broader phenomenon.) The shaman is the best at the tribe at this, but the general sort of experience is not unique to them.

The priest, on the other hand, operates in a society of greater hierarchization and specialization — in a word, a “civilization”. (Though by this I mean only the literal “living in cities” and not a higher or better culture.) In such “civilized” religions (which would include, as I understand it, indigenous religions such as those of the Aztec empire), one becomes a priest via ritual investiture by other priests. There is some sort of transmission or ordination occurring in a formal structure embodying a set dogma.

For access to the divine in such a society, one must go through the socially and politically approved intermediaries, the priests; or, if that is insufficient, one is channeled into an approved monastic system to keep one’s visionary consciousness from threatening the power structure. Under priestly religions in hierarchical societies, heretical visionaries are repressed.

Of course, in actual messy human societies things sometimes get blended. Shinto was the state religion of Japan and has a formal hierarchy in which priests operate — but its roots in ancient shamanism still show through in “ko Shinto”, old Shinto. Mainline Christian sects have a formal hierarchy of priests, pastors, or ministers; but the emphasis on individual experience and spontaneity in Pentecostalism shows a bit of shamanism. (Which has made for an interesting blend in Korea.)

Campbell believed that the sort of social structure that enabled priestly religion started to break apart with the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, and that in the coming age we will need more the lion-hearted courage of the shaman than the piety of the priest.

And for the past ten or fifteen years, my work has been centered around the idea that the purpose of Neo paganismis to build religious practices suitable to that need, that takes inspiration from the direct experience of shamans and mystics but brings the key principles forward into an industrial age: a sort of “industrial strength shamanism”, if you will.

Of course there are hazards in this. We must avoid misrepresenting other cultures, or our own qualifications. We must not view native and indigenous people as either “noble savages” or ignorant primitives waiting for civilized wisdom.

But I believe that Campbell was right: priestly religions were the creation of agricultural civilizations, a phase of human existence we are leaving; and shamanism is among the sources we need to look to for inspiration to build religion for the twenty-first century and beyond. The cause of justice and human rights is not advanced by denying the validity of shamanism as a general concept.