As much of our content here at Patheos Pagan describes, interest in magic and witchcraft is on the rise these days. It also seems that there is more interest in hexing and “black magic” among Pagan folk and witches than there was ten or twenty years ago.

And its also true that these days are “interesting times”, in the sense of the apocryphal Chinese curse.

These facts may be connected.

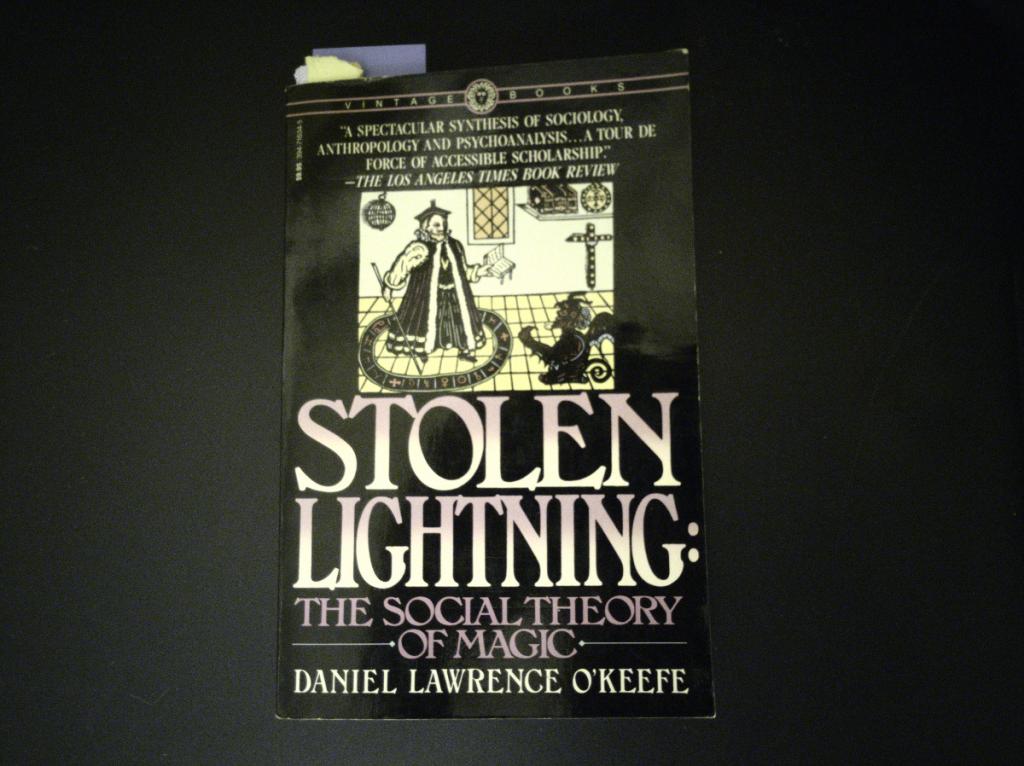

I recently started reading Daniel Lawrence O’Keefe’s book Stolen Lightning: The Social History of Magic. If O’Keefe is remembered today, it’s usually as the initiator of Festivus. Originally a family celebration of the anniversary of his first date with his wife, it was transformed by his son, a writer on Seinfeld, into a satirical winter holiday.

Professionally, O’Keefe was an editor at Reader’s Digest. Which was, in those days, a more respectable magazine than readers know today; he worked with writers like Ray Bradbury, Ishmael Reed and Czeslaw Milosz.

But he also had graduate degrees in sociology and philosophy, and it shows in his 1983 book Stolen Lightning, a scholarly book about magic from a sociological perceptive.

The book is structured as thirteen postulates about magic, and three of them seem of particular interest to the moment:

- Magic Is A Form of Social Action

- Magic Tries to Protect the Self

- Magic — Especially Black Magic — Is An Index of Social Pressures on Selves and Individuals[O’Keefe, 21]

Stolen Lightning is not easy reading — a contemporary New York Times review by Mark Glazer said “this multifaceted volume is simply bewildering in its discussions of psychology and in its use of anthropological theory. Quite simply, it lacks the one magic a book must have – the magic of coherence.”

And it’s not a “how to” book, or a history of Neo paganismor Euro-American magical societies. O’Keefe’s perspective is not that of a practitioner. He is looking at magic as a sociological phenomenon.

But that perspective is quite interesting to those of us who take a physicalist, non-supernatural approach to magic. And it results in some interesting ideas about the place of magic in society, which seem highly relevant to today:

This study began with a problem in sociological theory, especially with Durkheim and Weber. Why did Max Weber use the word magic on almost every page and never define it? What is magic? I got my first lead from two short sections in Durkheim’s impressive study of religion as the worship of society. In thirteen sharp pages it stated that magic is something anti-religious that develops out of religion. Why? In certain writers in the Freudian tradition I saw a hint of an answer: Magic is symbolism expropriated to protect the self against the social.[O’Keefe, xviii]

…My deduction: Magic defends the self against society.

What, then, is magic? If religion is the projection of the overwhelming power of the group, and if magic derives from religion, but sets itself up on a somewhat independent basis to help individuals, and is, at the same time, frequently reported to be hostile to religion…then is not the answer apparent? Magic is the expropriation of religious collective representations for individual or subgroup purposes—to enable the individual ego to resist psychic extinction or the subgroup to resist cognitive collapse.[O’Keefe, 14]

In a later footnote, O’Keefe quotes anthropologist-psychoanalyst Gèza Róheim’s Magic and Schizophrenia:

“We grow up through magic and in magic…Our first response to the frustrations of reality is magic; and without this belief in ourselves…we cannot hold our own against the environment and against the superego….In magic, mankind is fighting for freedom.[O’Keefe, 334-5]

Some of this dovetails nicely with one of the central ideas that has guided my work over the past decade or so, and which I explore in Why Buddha Touched The Earth. This is an observation from Joseph Campbell made in his essay “The Symbol Without Meaning”, where he discusses the difference between shamanistic and priestly religions.

Campbell points out that in gatherer-hunter societies, there is little specialization; individuals typically practice all elements of their culture. While each person has their talents, everyone does everything. That includes religion: the mystical experience is available to all. Even though the tribal shaman was the best at entering that state, anyone might go on a “vision quest”.

But civilized agrarian societies evolved specialization in every field, including religion. Organized priestly religion became a way to resolve humans to their confined, limited roles. Access to mystical states of consciousness was restricted to specialized devotees authorized by the power structure. [Campbell, 142-145; 157-164 ] Where the distinguishing characteristic of a shaman is their relationship with the spirit world, one can only become a priest via a ritual investiture by the existing power structure.

This is the sort of religion that O’Keefe is referring to as “the projection of the overwhelming power of the group”.

Campbell points out that the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution broke apart that pattern of civilized agrarianism, and we are entering a whole new era in human existence. That new era, says Campbell, calls for a new approach to matter of religion and the spirit, one where we will each need more of the courageous heart of a shaman than the piety of a priest.[Campbell, 189-192 ]

It seems to me this is where the Neopagan revival comes in: an opportunity to build a new sort of religion suitable for that new era, where “priests” are “first among equals” who are distinguished by their personal mana and skill rather than investiture by the established hierarchy.

In O’Keefe’s view, throughout human history magic has served as a form of resistance to the conformity-inducing sort of religion.

And thus, it seems to me, magic is also suited to a time when we need a political resistance.

As I mentioned, Stolen Lightning is structured as thirteen postulates about magic. Over the coming weeks and months it’s my intention to investigate each of these postulates.

So stay tuned for a deep dive in the nature of magic and its relation to society.

Print References

Campbell, Joseph. The Flight of the Wild Gander. New York, N.Y: HarperPerennial, 1990.

O’Keefe, Daniel L. Stolen lightning : The social theory of magic. New York: Vintage Books, 1983.