In the last entry which featured Ash Wednesday, it was argued that a liturgy that makes no space for lament caters to the “haves.” A liturgy of suffering features the “have-nots.”[1] A truly Christian liturgy rightly conceived accounts for both lament and celebration, and in view of Jesus’ cruciform glory, must move through lament to celebration. Thus, we must keep Lent if we wish to honor Easter.

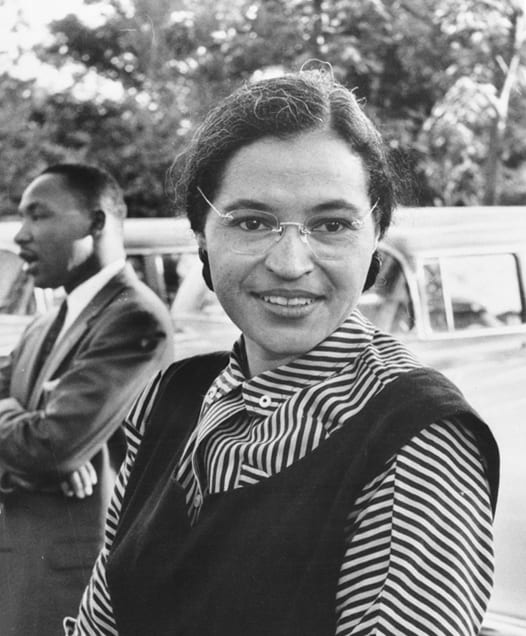

Black History Month, which runs throughout February, often overlaps with Lent, which begins in February or March. Black History Month accounts for lament and celebration. It laments the oppression committed against African Americans and celebrates their achievements in the face of overwhelming obstacles. Like the Lenten and Easter seasons, Black History Month moves through lament to celebration.

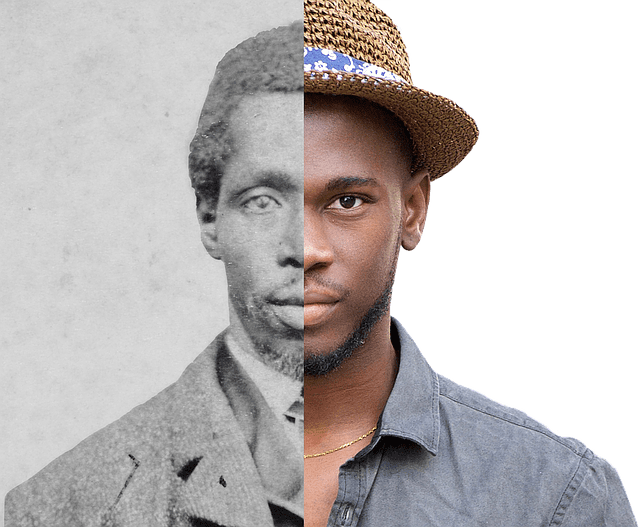

James Cone, the Father of Black Theology, rightly highlighted the need for Christian theologians to prioritize themes of oppression and liberation. He went so far as to call Jesus black, as Jesus identifies with the oppressed or have-nots against oppression.[2] Indeed, Jesus liberates the poor, the downtrodden, the marginalized in an all-encompassing manner of soul and body. As we find in Matthew 5, Jesus blesses the poor in spirit, just as he blesses the poor in Luke 6, while cursing the rich oppressors (similar themes appear in James 1 and 2). We must account for both passages in distinct though inseparable relation. Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart put the matter well:

In Matthew the poor are “the poor in spirit”; in Luke they are simply “you poor” in contrast to “you that are rich” (6:24). On such points most people tend to have only half a canon. Traditional evangelicals tend to read only “the poor in spirit”; social activists tend to read only “you poor.” We insist that both are canonical. In a truly profound sense the real poor are those who recognize themselves as impoverished before God. But the God of the Bible, who became incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth, is a God who pleads the cause of the oppressed and the disenfranchised. One can scarcely read Luke’s gospel without recognizing his interest in this aspect of the divine revelation (see 14:12-14; cf. 12:33-34 with the Matthean parallel, 6:19-21).[3]

Many white Evangelical Christians may argue that all this about the Black Jesus, oppression and liberation is nothing more than identity politics and a form of social gospel. They easily forget that every theology has an identity that is culturally and politically embedded. What passes for authentic theology and liturgy is often no more than a contextualized Eurocentric ethnic form of theology that caters to dominant culture ways of life that have become homogenized due to familiarity. They also appear to replace a social gospel with an otherworldly gospel. In contrast, the whole gospel features salvation of the whole person in the whole community where the kingdom of heaven flourishes on earth. In place of a materialistic social gospel or a pie-in-the-sky asocial gospel, the gospel is relational and social and addresses our total human condition.

What is needed, then, is a liturgy that accounts for blackness, namely themes of oppression and liberation, and not simply personal salvation. Just like the church historically accounted for red martyrdom (persecution where Christians shed their blood for their faith) and white martyrdom (asceticism/monasticism where Christians deny themselves for their faith),[4] we need to account for black martyrdom. Black martyrdom involves living in solidarity with the oppressed in view of Jesus who comes to set the captive free.

The US calendar formally features black history only one month of each year. The rest of the year generally features white history. Lent only occurs over forty days during the church calendar cycle. But we must not allow it to recede into distant memory as we proceed toward Easter and Ascension. After all, “the black Jesus” became poor so that we could become the riches of God (2 Corinthians 8:9). When he ascended, he led captives in his train and gave gifts to humankind (Ephesians 4:8). Here I am not promoting a form of prosperity gospel teaching, simply that God cares for the whole person and brings about liberation from oppression for the captive and seeks to make us spiritually, physically and socially whole through the realization of God’s eschatological kingdom in which we participate presently and which will be realized in full one day.[5] The vital connection between Lent, Easter and Ascension signifies that Jesus’ glory ever remains cruciform.

As noted in the last entry, forty percent of the psalms feature lament,[6] and all four gospels give significant attention to the way of the cross and Jesus’ passion. Given these factors, maybe we should feature lament in our liturgy forty percent of the year. In that case, forty plus days of Lent are not enough. Nor are thirty days for black history. We must account for lament as well as celebration, along with black martyrdom, throughout the year, if we are to cherish the have-nots with whom Jesus identifies as the Suffering Servant and man of sorrows, familiar with suffering (Isaiah 53:3).[7]

_______________

[1]Walter Brueggemann, Peace (St. Louis: Chalice Press, 2001), pages 26-28.

[2]See James H. Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation, Twentieth Anniversary Edition (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1990), pages 119-124.

[3]Gordon Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All Its Worth, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1993), page 125.

[4]There are at least four forms of martyrdom discussed in various sources: red, white, blue, and green. Thomas Cahill discusses “green martyrdom” and associates it with the distinctive witness of Irish monasticism. See How the Irish Saved Civilization: The Untold Story of Ireland’s Heroic Role from the Fall of Rome to the Rise of Medieval Europe, The Hinges of History (New York: Anchor Books, 1996). Red stands for the shedding of blood and death. White stands for asceticism. Blue stands for penitence. Here’s a brief summary of these three forms: “White martyrdom was the daily living of the ascetic life for Christ’s sake; red, of course, meant the shedding of blood and death itself for Christ’s sake. Blue martyrdom, which seems to have been a particularly Irish development, stood for the way of the penitent in penance, in bewailing of sins and in labour.” Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, and Edward Yarnold, S.J., eds., The Study of Spirituality (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), page 221.

[5]Note that while many white Evangelicals look down on the prosperity gospel movement, we have a tendency to promote it in more subtle terms with our implicit or explicit adherence to a riff off of Max Weber’s thesis of the Protestant work ethic. Prosperity reflects assurance of God’s favor and blessing as a result of our hard work.

[6]Glenn Pemberton, Hurting with God: Learning to Lament with the Psalms (Abilene: Abilene Christian University Press, 2012), Kindle loc. 441-445.

[7]Here it is worth accounting for Cone’s connection between the Suffering Servant and the Black Jesus: “If Jesus is the Suffering Servant of God, he is an oppressed being who has taken on that very form of human existence that is responsible for human misery. What we need to ask is this: ‘What is the form of humanity that accounts for human suffering in our society? What is it, except blackness?’ If Christ is truly the Suffering Servant of God who takes upon himself the suffering of his people, thereby establishing the covenant of God, then he must be black.” Cone, A Black Theology of Liberation, page 122.

I engage the themes of Black History Month, Lent, lament, and celebration in my recent book, Setting the Spiritual Clock: Sacred Time Breaking Through the Secular Eclipse (Cascade, 2020). Here is the trailer for the book.