This post is part of a series on Aquinas, Aristotle, and Edward Feser’s explanation of them both.

I said in my first post on Edward Feser’s book that I have deep Aristotelian sympathies. The four causes seem like a coherent way of describing the world, even if I’m not confident they’re the territory, not just an approximated map. But if I’m willing to give a little ground there, how do I avoid believing in a First Mover?

That was the question the Dominans asked me, when I was discussing Feser’s book with them this past weekend. Well, to be honest, I think an Aristotelian First Cause, that holds everything in the universe in existence, is a plausible hypothesis. The trouble is, Feser and Aquinas label that cause ‘God’ awfully fast, but that word is linked to a whole mess of other qualities that are not necessarily true of a being whose essence is existence.

Feser didn’t spend much time showing a logical connection between the First Mover and a personal God that has any particular stake in humankind. He does a little with Aquinas’s Fourth Way showing the First Mover has all perfections fully, and I’ll come back to that point in a later post. A lot of Feser’s argument, once he lays out Aristotelian metaphysics, is that the god of Christianity looks like the best match for this being. I’m not going to make a rigorous study of relative probability, but I’m going to give a couple of examples of things that might be able to play the role of First Mover, without looking anything like a deity.

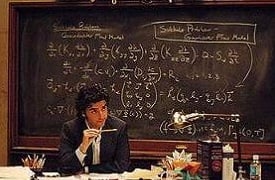

1. The big equation

From Tom Stoppard’s Arcadia:

If you could stop every atom in its position and direction, and if your mind could comprehend all the actions thus suspended, then if you were really, really good at algebra you could write the formula for all the future; and although nobody can be so clever as to do it, the formula must exist just as if one could.

I take what is apparently a very Platonist position on math. I don’t treat it as the relationships that humans make between concepts we abstract from day to day life. I don’t think I get the concept of ‘two-ness’ from seeing two apples, and then two people, and then two houses and abstracting away from the objects to see what they have in common.

I think of mathematical truths existing prior to human cognition and abstraction. The relationship goes the other way. The apples and the people and the houses are all similar insofar as they share in the form of two-ness, which exists independently of material things to exist in pairs or human minds to think about them.

So, although I can’t do the metaphysics rigorously, it seems plausible that the equations that govern our world have some kind of independent existence that don’t depend on any Prime Mover. And if those relationships are defined in sufficient detail, the rulebook is essentially a spanning set for the entire universe — everything else logically follows from composing these rules, so, once the math exists, everything else follows.

I’ll note one problem with this idea right now: it might be that you need some parameters to go with these equations, to set a starting value. I might have to come up with a cause for those parameters, but it might also be the case that the equations are only satisfied by one set of values, in which case, their cause — like everything else — is only contingent on the equations.

2. All of space-time

Let me give another possible example. Aquinas’s writings (as summarized by Feser) place God outside of time and us in it. From moment to moment, Aquinas’s god sustains the universe in existence. I’m kinda wondering if I can categorize the entire universe as one composite being.

There are at least three dimensions, and I can define points in the universe by setting values for each of these three coordinates (provided I’ve stuck an origin somewhere). But time can be treated as an additional, non-spatial dimension. Just as a cube is the composition of an infinite number of 2D squares, the space-time continuum is the composition of all states our universe has ever been in and will ever be in.

This composite exists outside of time, and therefore does not change. Absent change (or motion) there’s no need for a first mover. So possibly, what I’ve just talked myself into is the idea that this space-time object is really real, which seems plausible, if not provable.

3. Look, my understanding of M-theory is impoverished

Possibly wrapped up in those 11-dimensions are objects/beings that don’t seem to depend on a First Mover in ways similar to ideas one and two above, but it’s been a while since I read Alice in Quantumland or Flatterland, so my intuitions are rusty.

But the reason I want to bring this up at all is because we think of Quantum as weird or counter-intuitive when, as Yudkowsky points out, quantum is, as far as we can tell, that which is, and it’s not quantum mechanics’s fault that our intuitions are flat out wrong.

I think you can still make most of Aristotle’s and Aquinas’s arguments in the face of things like particles and antiparticles coming spontaneously into existence or all electrons actually being a single time-traveling electron, but I’m not sure. If there are links to neo-Thomists who get into this, I’d be very interested to see them.

Long story short, even if I concede there needs to be some being that is pure Act and can unite essences with existence at every moment in time, that’s a long way from thinking that Act is an entity I should worship or could have any relationship with at all. Full disclosure, this isn’t my true rejection; I’m not confident enough in Aristotle’s metaphysics or their correspondence to reality that, if the options I’ve outlined above were off the table, I’d become a deist.

This post is part of a series on Aquinas, Aristotle, and Edward Feser’s explanation of them both.