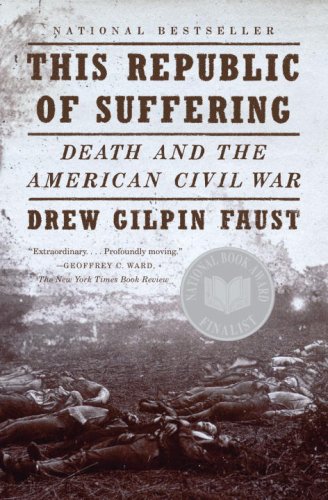

Given the way our discussion of pacifism has meandered over to a debate about martyrdom, what you want to “accomplish” with your death (and whether that’s a coherent question), I’d like to recommend something for your summer reading list: Drew Gilpin Faust’s This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War. It’s a fabulous book. It doesn’t presuppose that you’re a Civil War buff, so casual readers have no barrier to entry, and it delves into a strange, tightly-circumscribed topic, so even people who already know a lot will probably still find new data and analysis.

I struggled a little with my choice of adjective above, since death isn’t really a strange subject; it’s the one we’re all guaranteed to encounter. But our experience with it is almost always as something unnatural. Gilpin Faust ends up focusing a lot on how nurses and chaplains ended up scripting a good death for their charges. Because soldiers were dying en masse far from home, letters describing their deathbed scenes ended up mapping out what the cultural expectations were for a successful death. Go put a hold on the book at your local library.

One topic from a later chapter is more directly relevant to where we started: the ethics of being a soldier. According the Gilpin Faust’s sources, the Civil War was the first American war to rely heavily on sharpshooters and snipers, and people struggled to fit their actions into the killing-but-not-murder paradigm:

To shoot a man as he defecated, or slept, or sat cooking or eating, or even as he was “sitting under a tree reading Dickens,” could not easily be rationalized as an act of self defense. Soldiers in camp wanted to think of themselves off duty as targets as well as killers, and they found the intentionality and personalism involved in picking out and picking off a single man highly disturbing. Union sharpshooting units customarily wore green uniforms to serve a camoflage and Confederates came to refer to these marksmen as “snakes in the grass.”

The cool calculation, the purposefulness, and the asymmetry of risk involved in sharpshooting rendered it even more threatening to basic principles of humanity than the frenzied excesses of heated battle. When twelve soldiers from a regiment of Union sharpshooters were taken prisoner in Virginia in 1864, a local Petersburg newspaper argued for their execution: “in our estimation they are nothing but murderers creeping up & shooting men in cold blood & should receive the fate of murderers.” After enduring twenty-four days of steady and debilitating sniper fire between Union and Confederate troops near Port Hudson, Louisiana, John De Forest confessed “I could never bring myself to what seemed like taking human life in pure gayety.” Men who had displayed great courage in battle had broken down “under the monotonous worry” generated by sniper fire. De Forest judged it a “sickening, murderous, unnatural, uncivilized way of being.” Men who could kill others in this way were not men as De Forest before the war had understood them to be; they violated his assumptions about both human nature and human civilization; he believed they undermined what defined their human selves.

I didn’t expect the text to be such a perfect echo of the debate over drone warfare today. But what’s really jarring is that it’s not an echo of debates over sniping and general long-range killing. In the hundred fifty years since the Civil War, what struck soldiers as inhuman has become part of our baseline expectations for war. It’s a ratchet effect.

I’m going to be writing more about drone warfare and how much distance it places between us and our actions later this week, but, in the mean time, I’d really like to hear from you guys on what heuristic you would use to decide that a certain way of killing people is unacceptable. I’ll assume we all agree you should minimize the suffering of your victim, but is there anything besides that and efficacy that you need to keep in mind?