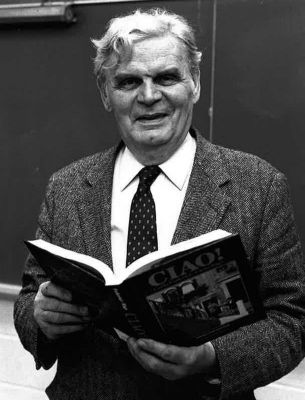

In the spirit of Stephen Colbert’s eulogy for his mother, I’d like to share some stories today about my high school Latin teacher, Dr. Vladimir Rus, who passed away this past week. We never called him Dr. Rus; he was always simply Magister. So it was easy to forget what his usual name and title was. One day, after another teacher had popped into our classroom to ask him a question, one of my classmates to ask, “Magister, what is your doctorate in?” He looked a little abashed and told us, “I am sorry to tell you, it is in German.” He seemed to be worried that we would feel cheated that it was not in Latin.

When his Newsday obituary was published, I found out the origin of his accent:

Rus was born in [Czechoslovakia in] 1926. During World War II, he endured forced labor under the occupying Nazis, removing rubble and bodies after air raids in Munich.

After the war, he attended law school at Prague’s Charles University. But “after the Communists assumed power, they asked — and asked is probably a euphemistic way of putting it — if he would essentially be a spy on his law teachers, which he declined to do,” Tom Rus said.

Instead, Vladimir and his older brother Svata crossed the border into Germany. Because Svata had the only winter coat, he traveled northwest to England; his younger brother headed south to Italy, according to a family legend.

Rus spent two years in a displaced persons camp before sailing to South Carolina, where he became a University of South Carolina undergraduate.

I had him for Latin after he was technically retired. I overheard him ask the department chair incredulously why the school did not have a record player (he wanted to play us “Gaudeamus Igitur”). After the first class of the year, a group of us gathered incredulously in the hallway to compare handouts. “This isn’t a font, right? These are actually typewritten!” And, most notoriously, Magister seated us in meritocratic order. Just like there’s first chair in an orchestra, he had us sit in sequence according to how well each of us could answer the question “Scisne latine?”

In addition to simple dialogues and stories, Magister sometimes pulled out surprising texts for us to practice translation. A few lines into a dialogue he handed us called “Quis erat in primum?” I realize I was reading Abbot and Costello’s “Who’s on First?” sketch.

Later in the year, we had a less pleasant translation task. Magister ended up hospitalized for about a month. The way the foreign language chair told it, he had noticed that his feet were swollen and wouldn’t fit into his shoes, so he called his doctor, and the following dialogue ensued:

“Doctor Rus, it sounds like you’re having symptoms of kidney failure. I need you to come in right away.”

“Very well, it is a three-day week at school. I shall be able to see you on Thursday.”

“Doctor Rus, I said it sounds like you’re experiencing kidney failure. I need you to come in right now!“

We sent flowers to the hospital, and he sent back a thank you note, in Latin, with footnotes to define and note the declension of any words he hadn’t taught us yet.

He never used our first names at all. I was always Discipula Libresco in that class. When one of the two Gabrielles came in one day with a late pass (“Please excuse Gabby…”) he read it over and began chortling. He proclaimed, “I see your name is Gabby. I shall have to call you Loquax!”

Sometime in the spring semester, one of the senior girls (Discipula Cohen – not her real name) had cut class a few times. We were all still nervous about Magister’s health, and, I, for one, felt a little panicked as he stumbled at the beginning of class and peered with confusion at my classmate.

“Who are you?”

“What?”

“Who are you?”

“What? It’s me, Discipula Cohen!”

“Who?”

“Discipula Cohen! I’m in your class! I have been all year!”

“Perhaps it has been so long since I have seen your face… that I have forgotten what you look like.”

It has been eight years since I have been in Magister’s classroom, and he is still indelible. He was in love with languages and with teaching. In high school, I had a number of teachers who tried to mollify students or apologize for their own curriculum — trying to show us that they were on our side. But Magister began each period without any doubt that he was teaching us something beautiful and valuable, and I found his joy infectious. When I’ve spoken to old teachers and friends, I tended to ask, “Is Magister still teaching?” His reverence for his subject was startling and lovely. I’m so grateful he shared it with so many discipulorum Magister.

Vivat academia!

Vivant professores!

Vivat membrum quodlibet;

Vivant membra quaelibet;

Semper sint in flore.