My family often celebrates New Year’s Eve by watching a very long movie (i.e. Gandhi) on New Year’s Eve, when we’re committed to staying up to finish it.

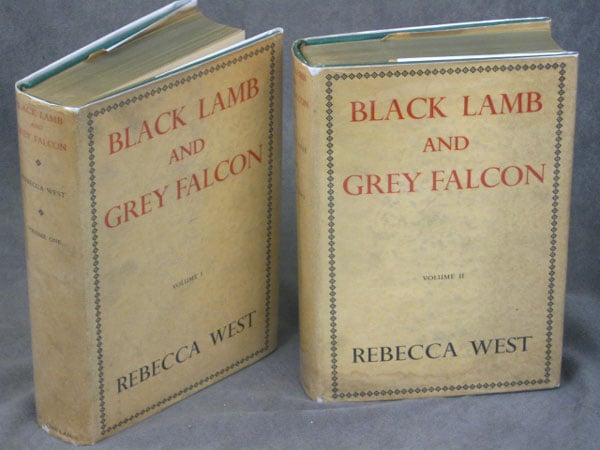

If you’d like to pick up that tradition but in a literary vein, why not welcome in the new year while reading Rebecca West’s Black Lamb and Grey Falcon: A Journey Through Yugoslavia.

I read it this month because all my cool friends were reading/had read it, and I’m very pleased to have done so (though my boyfriend now insists I read Kaplan’s Balkan Ghosts for balance).

Black Lamb and Grey Falcon was written between the world wars, as Dame Rebecca West traveled through Yugoslavia. It blends travel writing, character studies of traveling companions (including the despicable Gerda), historical context/digressions, and theological reflections. It’s one of the books I got out from the library and ordered my own copy of when I was about halfway through.

And, rather than try to describe it in my own words any further, here are some passages I dog-eared on my way through.

In the West conversation is regarded as a means either of passing the time agreeably or exchanging useful information; among Slavs it is thought to be disgraceful, when a number of people are together, that they should not pool their experience and thus travel further toward the redemption of the world. In the West conduct follows an approved pattern which is departed from by people of weak or headstrong will; but among Slavs a man will try out all kinds of conduct simply to see whether they are of the darkness or of the light. The Slavs, in fact, are given to debate and experiment which to the West seem unnecessary and therefore, since they must involve much that is painful, morbid.

Franz Josef’s Chamberlain, Prince Montenuovo, was one of the strangest figures in Europe of our time; a character that Shakespeare decided at the last moment not to use in King Lear or Othello, and laid by so carelessly that it fell out of art into life.

“But you always say you hate scenes,” said my husband.

“So I do, when I am well, there are so many other things to do,” I answered; “but when I am ill itt is the only incident that can cheer me and reach me under the blankets. And it really is sensible to show emotion at serious illness. Death is a tragedy. It may be transmuted to something else the next minute, but till then it is a divorce from the sun and the spring. […] I am quite sure it must be more exhilarating to die in a cottage full of people bewailing the prospect of losing one and the pathos of one’s destruction than to lie in a nursing-home with everybody pretending that the most sensational moment of one’s life is not happening.”

Here [on a visit to a tuberculosis ward –LL] is the authentic voice of the Slav. These people hold that the way to make life better is to add good things to it, whereas in the West we hold that the way to make life better is to take bad things away from it. With us, a satisfactory hospital patient is one who, for the time being, at least, has been castrated of all adult attributes. With us, an acceptable doctor is one with all asperities characteristic of gifted men rubbed down by conformity with social standards to a shining, cornerless, blandness. With us, a suitable hospital diet is food from which everything toxic and irritant has been removed, the euchunchized pulp of steamed flesh and stewed prunes. Here a patient could be adult, primitive, dusky, defensive; if he chose to foster a poetic fantasy or personal passion to tide him over his crisis, so much the better. It was the tuberculosis germ that the doctor wanted to alter, not the patient; and that doctor himself might be just like another man, provided he possessed also a fierce intention to cure.

(You can all send me your thanks when you finish next month)