Alex Knapp took issue with my quasi-Platonism (and possible math idolatry) over at his tech blog for Forbes. Here’s the crux of his argument:

The bottom line is that human beings have brains capable of counting to high numbers and manipulating them, so we use mathematics as a useful tool to describe the world around us. But numbers and math themselves are no more real than the color blue – ‘blue’ is just what we tag a certain wavelength of light because of the way we perceive that wavelength. An alien intelligence that is blind has no use for the color blue. It might learn about light and the wavelengths of light and translate those concepts completely differently than we do.

In the same way, since the only truly good mathematicians among the animals are ourselves, we assume that if we encounter other systems of intelligence that they’ll have the same concepts of math was we do. But there’s no evidence to base that assumption on. For all we know, there are much easier ways to describe physics than through complicated systems of equations, but our minds may not be capable of symbolically interpreting the world in a way that allows us to use those tools, any more than we’re capable of a tool that requires the use of a prehensile tail.

It’s a good attack on my metaphysics of math, but I think this line of attack takes a lot of other abstract ideas down with it. In fact, it’s so broadly applicable that it raises the possibility that this line of attack is self-refuting, depending on how confident we are that parts of our subjective experience count as ‘real.’

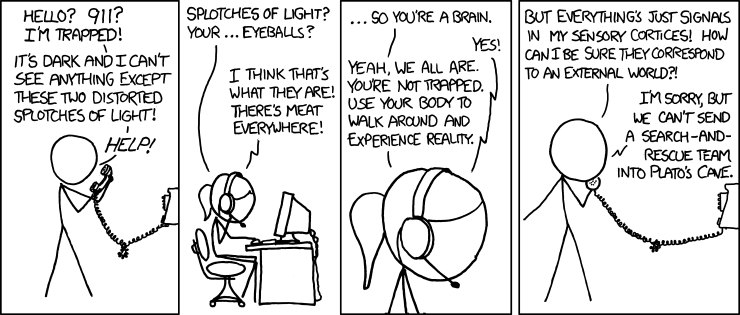

Let’s start by expanding Knapp’s point about ‘blue’ being a human-dependent label for an arbitrary span of light wavelengths. If we’re trying to go to the absolute base level of ‘real’ we can go a lot further. Quantum wave functions are the most fundamental we’ve gotten, and you can make the argument that they’re what’s what’s really real and that humans are just an artifact of scale, of putting arbitrary labels on phenomena too big for us to understand.

That’s the endpoint of this argument, but you’re probably more familiar with it’s application to moral judgement. Talking about The Good is a labeling error. We may be able to say some things seem more or less good, but it’s all continuous and who’s to say we’re looking at the whole thing with the right metric, anyway? Maybe being SuperHappy is the most babyeating thing you can be. [See “Three Worlds Collide” a short story by Yudkowsky if that last sentence didn’t make sense].

Knapp’s argument isn’t excluding math from the category of Forms, it’s denying the existence of any Forms at all. I think that’s too much epistemological modesty. At the very least, the evidence for math is compatible with my explanation as well as Knapp’s. He thinks the correspondence between abstract math and physical phenomena shows that we generalized from our experience. I think it means we get a sense of something we can’t perceive directly by seeing it imbued in the physical world. We see it by its shadow.

You can accuse me of multiplying entities past what is required for an explanation, and you may be right. But if you think that there’s some kind of external metric for judging our actions, that we have imperfect, indirect access to, and isn’t something that necessarily corresponds to dominant game theory/evolutionary strategies, you’re going to have to come up with a criteria that specifically disqualifies math from fitting into the Form-like category you’ve reserved for morality. If you’re comfortable jettisoning all of these transcendentals, that’s going to be a much longer and harder fight.