Virgin births are not nearly as miraculous as you think.

They happen fairly regularly. Well, I don’t know about regularly, but they do happen, and they aren’t considered rare.

There are documented cases among lizards, snakes, sharks, rays, turkeys, chickens, and other vertebrates — including lots of insects.

Scientists call virgin births parthenogenesis (literally, originating from a virgin). The female produces offspring asexually, apart from male involvement.

Scientists know that parthenogenesis occurs because they are able to perform genetic testing, which reveals (in these cases) that the genetic material of an off-spring is identical or nearly so to a single parent, the mother, rather than a mix of genetic material from a male and female.

They have discovered parthenogenesis by accident, when, in captivity, a female is found to be with child, but with no father in sight.

This happened December, 2001, only a few weeks from Christmas eve, when a hammer head shark gave birth in an aquarium. This was most surprising since she had been taken into captivity while she was well before birthing age, and, ever since her captivity, had only lived with other females. The Marine biologists were shocked to discover the newly born pup – which tragically was killed by a stingray hours after it was born. Genetic testing matched the baby and the mother – and revealed that the baby had no genetic material from a father.

Then, in 2008, at the Virginia Aquarium in Virginia Beach, a blacktip shark named Tidbit was also discovered pregnant. She died before she could give birth to the 12-inch long pup fetus, which was only discovered during her autopsy. Demian Chapman, one of the researchers, noted that there “were no male blacktip sharks in the tank for the entire time of her captivity.”

DNA testing showed that her pup’s genetic material was derived entirely from her mother. There was no father in sight, either in the aquarium or in the pup’s genome.

Scientists don’t call asexual reproduction, in non-human animals, a miracle. They have natural explanations for it. A National Geographic story which described the discovery of parthenogenesis among smalltooth sawfish in the rivers of Southwest Florida, explains the process of virginal conception:

Essentially, in virgin birth, a female is able to fertilize her own egg and produce offspring. It occurs when material that’s split off from an egg as it divides—called a polar body—fuses back with the egg. It’s similar to how sperm fuse with an egg during fertilization.

Granted, just because there’s an explanation and a technical term for it, doesn’t make it unremarkable.

These occurrences sound unbelievable to those of us who don’t read Natural Geographic or Science magazine regularly. They aren’t miraculous.

But they do show that nature has a remarkable way of continuing life, perhaps especially in the face of grimly declining numbers.

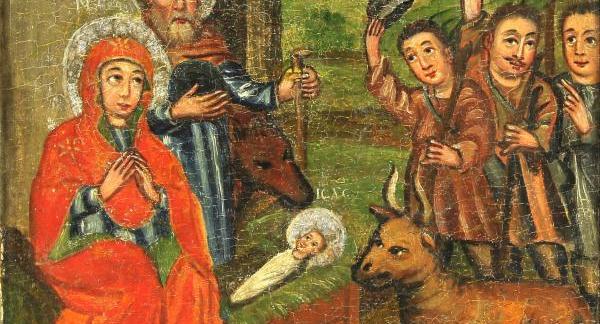

But what does all this have to do with the Christmas story?

The occurrence of virgin births in non-mammal species does not serve to legitimate belief in a literal virgin birth of Jesus by Mary through the Holy Spirit.

While parthenogenesis is real and does happen, it hasn’t been scientifically documented in mammals, and certainly not in human beings, despite a number of efforts to do so over the years. There’s something apparently unique to mammalian species that requires the input of both male and female genetics. And for human life, we just can’t do without the egg and the sperm.

Side note: for a interesting overview of some of those efforts, and for an extensive explanation of why virgin births prove impossible thus far in mammals (and humans specifically) see Aarathi Prasad’s endlessly fascinating book, Like a Virgin: How Science is Redesigning the Rules of Sex. She also details an interesting thought experiment: What if Mary had actually given birth to Jesus parthenogentically — from a scientific/biological perspective? (quick summary: She would have had to have been intersex, and the baby Jesus would have had to have been a girl, not a boy).

But of course from the perspective of many believing Christians, science can’t definitively answer the question of whether the virginal conception of Jesus did or didn’t take place, literally, historically, biologically, etc.. Furthermore, many Christian believers could care less about the science, one way or the other (which I find rather unfortunate). For them, a miracle is a miracle, and if God did it, God did it – and that’s that.

But, as I reflect on it this Christmas, I have to wonder whether the presence of parthenogenesis in nature is yet another reason to think again — and differently — about the virgin birth story.

I’ll be exploring the implications more fully in coming days as I continue work on a book about the virgin birth.

What do you think?