Roma begins in water.

It’s all we see at first—the water washing over black-and-white tile like a tide. Most movies, if they contained a scene like this at all, would hold the shot for just a second or two. But director Alfonso Cuarón lingers here for minutes, and in so doing the moment unfolds like a flower. We see not just the water, but the tile underneath, the soap bubbles clinging to the surface, the reflection of a faraway plane, the whisper of its engines perhaps barely audible above the water’s own silver hiss and gurgle.

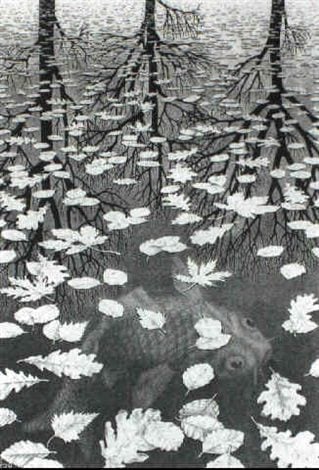

It made me think of “Three Worlds” by M.C. Escher: A picture of a lake, its surface dotted by leaves, the reflection of bare trees and, under the surface, a fish. Reality in layers.

It made me think of “Three Worlds” by M.C. Escher: A picture of a lake, its surface dotted by leaves, the reflection of bare trees and, under the surface, a fish. Reality in layers.

And it seems as though Cuarón was reaching for a moment of transcendence, something belonging to both heaven and earth. It’s a reflection of the countless moments in our lives that we never even notice. Cuarón makes us see it.

Roma, is that sort of film—both movie and meditation, prose and poetry, a thing at once very concrete and deeply spiritual. To me, it also feels like a reminder: There’s not just beauty in the humble things, but glory.

Roma is, on some levels, a hard sell for the average American moviegoer. It’s black-and-white. Not a word of it is in English, Cuarón preferring Spanish and Mixtec (a language of the indigenous people of Mexico) instead. And its story is, on the surface, a modest one. Rooted in the director’s own childhood memories, Roma spends a year with an upper-middle-class family living in Mexico City, circa 1970 and ’71. Its protagonist, Cleo, is a domestic servant who works for that family: The water in that opening scene, we see through her eyes.

Could Cuarón have picked a more humble hero? Could there be anyone more overlooked in that place and time? I don’t think so. She works quietly, without drama. She’s cast aside by someone who professes to love her. The people she works for—the people she lives with—know next-to-nothing about her. When the family’s grandmother, Teresa, tries to check Cleo into a hospital, Teresa realizes she doesn’t even know how old Cleo is.

Cleo’s the antithesis of an American-style protagonist: a true antihero. Our culture values strength and ambition. Our cinematic heroes are sacrificial, yes, but in the showiest of ways. There’s nothing showy or ostentatious about Cleo: She’s not gorgeous or brilliant or witty or powerful. She does the most menial jobs for menial pay, and we never get a sense that she expects or aspires to more. She seems like she’d be utterly forgettable.

But as we see in the opening scene, Cuarón’s patience allows Cleo’s beauty and her strength to unfold. We see the power and depth of her love for the children in her care. Her every act is imbued with humble grace. We see her agony, her sacrifice and most especially, her love for the kids in her care: fierce, tireless, giving and forgiving.

Through Cuarón’s artistry and patience, we come to see Cleo as a hero not in spite of who she is, but because of it. The director helps us to see her a bit, I think, like God does.

Servanthood is relentlessly unsexy. Humility is practically anti-American these days. Even Christians—maybe especially Christians in these angry anxious times—seem to eschew such things, embracing instead the anger of the age and chasing after scraps of power and prestige. We see it in our movies, too. Many of the year’s buzziest films deal with big issues: They give us protagonists who fight fearlessly and stubbornly against the evils they see, be it racism or sexism or some other ism. They trumpet strength and power and tireless righteousness. And that’s great. We should admire these heroes. Society needs them often.

But Cleo shows us a different example—one rooted in Scripture.

A friend of mine said Roma was “Mary’s Magnificat in black and white,” and I love that comparison of that beloved, ancient canticle:

My soul doth magnify the Lord.

And my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour.

For he hath regarded : the lowliness of his handmaiden.

Not being as steeped in Christian tradition as my friend, my mind gravitated instead to the Beatitudes: “Blessed are the poor in spirit,” Jesus said. “Blessed are those who mourn … the meek … those who thirst for righteousness … the merciful … the pure of heart … the peacemakers.”

I don’t want to spoil the movie, but Cleo embodies those Beatitudes. And with Cuarón’s help, we can see something we rarely see in the world and its values: We see them as blessed. Beautiful. Glorious.

Roma has some content issues, of course, including an extended scene featuring male nudity. But personally, I think Roma is a must-see for those who can deal with the content. And if you see it playing in a theater somewhere, see it there: Cuarón’s cinematography deserves a big canvas. Of all the films I’ve seen this year, this is the one I most want to see again.