When I was in 6th grade, my younger sister had to do a family tree project for school. She sat down with our mom and filled out our grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ names. That’s when she told us her maiden name, Bukosbe, wasn’t really Bukosbe. Her grandfather had changed the name from Bukowski because people gave him a hard time for being German.

Anyone familiar with names that end in -ski knows that’s not a German name, but we’ll get to that later.

When I was little, I used to ask my grandmother to tell me stories about her family. I was always more interested in listening to old family stories than playing in the backyard with my cousins. But even with all those stories, I didn’t know all that much about my ancestors.

And when I asked my paternal grandfather once about his grandparents, all he told me was his grandmother used to shout, “Get that dog out of the house!” in German, and that was all the German he knew. (He may or may not have been teasing me. It’s hard to tell sometimes with that side of my family.)

We cut ties with my mother’s father when I was ten, and after we moved to another state, I only saw her mother once. I never had the opportunity to ask questions, and my mom didn’t know much. Her father had told he was half French and half German, and that his parents spoke French and German and would curse each other out in those languages when they were angry. (Again, this might not be true.)

Sometimes, when a person moves around a lot and never has the opportunity to settle down and become part of a community, it sparks up this need to be part of something.

Well, I was part of my family, but what did that mean? Being a part of something means sharing certain values and a shared history.

So, I went looking for that history.

My paternal great-aunt got me started on researching genealogy on my dad’s side of the family. Over the years, I traced that branch back to my Bavarian immigrant ancestor who wound up becoming a brewmaster in Baltimore.

It was my mother’s paternal side of the tree that kept me stuck. I couldn’t get past my great-grandparents for over a decade. My mother and I took turns working on it for almost twenty years. We wanted to know where we fit in all of this.

My mother lucked into finding a cousin through some genealogy forums, and she gave us a lot of names and dates for her shared branch of the family. We threw them onto our tree, but names and dates don’t tell you all that much about a person. You’ve got to put them into their cultural and historical context.

I figured it might be interesting to read about the town my great-grandmother had lived in before her family moved to Texas. I did a Google search for Abbeville, Louisiana. Most people who lived there were descendants of Acadians, or Cajuns. I’d never heard anything about that before. When I looked at the names my mom’s cousin had given us, I found a long branch with common Acadian surnames. That whole “half French” thing had basically been true.

Around the same time, I finally got somewhere with the peskiest of my ancestors, those Bukowskis. After I moved to Michigan and met a lot of people with Polish ancestry and -ski surnames, I realized pretty quickly we were Polish on that branch, not German. I contacted a woman in Texas who had records for the Catholic church in the town my great-grandfather was born in. I found my great-grandparents and great-great-grandparents.

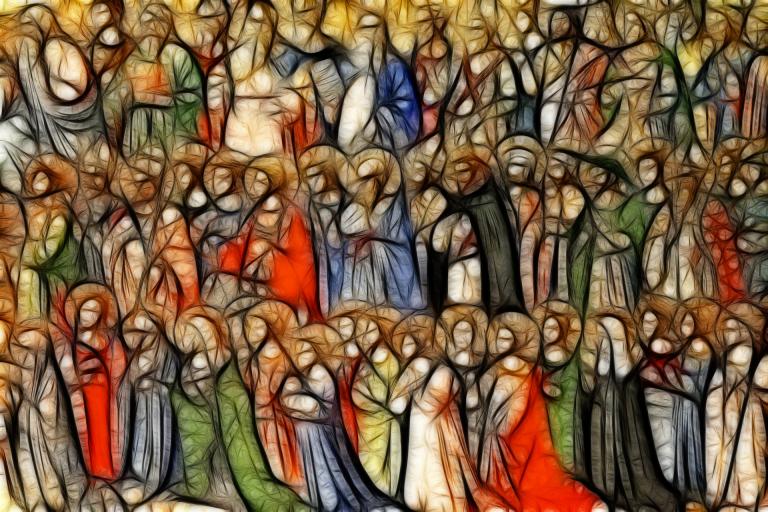

I also made contact with a cousin on my father’s side of the family who was able to provide me with more information about my paternal grandmother’s Italian side of the family. He even knew the town our ancestors were from. I found the town’s Facebook page and scrolled through pictures of a procession where people carried a statue of Mary through the streets.

I grew up (mostly) Mennonite, but I’d always known my mother had grown up Catholic. I’d always been curious about it and even sneakily read about some saints when I was younger. As I tried to understand the context my ancestors lived in, which would help me understand the context I’d been born into, I couldn’t ignore the Catholicism of it all.

I didn’t jump to convert just because my great-grandmother had been Catholic before marrying her Methodist husband, but I did start looking at Catholicism, from the perspective of a family historian. I wanted to understand how they lived, and religion is a huge part of how people live.

Learning about Catholicism was a slow process, especially since I grew up in a fundamentalist environment that was often extremely hostile toward Catholicism. Diving into it those first few times was actually frightening for me.

I bought my first rosary to see if that would help me connect with my family history better, and the first time I used it, I almost had a panic attack even though I’d left fundamentalism behind me more than ten years earlier. That mental conditioning runs deep.

When I did pray with that rosary, nothing happened. God didn’t smite me. The devil didn’t materialize in my bedroom to haul me off to hell. I didn’t feel that deep sense of guilt the way I do when I’ve done something I know is wrong. I felt fine. Actually, I felt like I had prayed, and I hadn’t been able to really pray for years.

I joined the church six years after praying with that rosary for the first time. Like I said, it’s been a slow process.

I’ve always been looking for my people. For a place where I fit. I’m thankful to my Catholic ancestors for helping to lead me to them, even if they might never had done it intentionally. Learning about them was one stretch of the path that brought me here.

My people aren’t necessarily Catholics, in general. I’ve been burned (almost literally) by church “families” before, so I’m not really down with being overly attached to people in a church. There are too many people who love evil and hate their brothers and sisters sitting inside churches, acting all pious. Those are definitely not my people. I don’t feel any sort of kinship with people who promote fear and throw vulnerable people under the bus.

My people are the saints.

That’s who I’ve been looking for: the living saints among us and the saints interceding for us in Heaven. I’m so in love with so many saints. We have shared values and a shared purpose. I don’t think Catholicism has a corner on that market. I’ve known many Christ-like people who aren’t Catholic. For me, personally, being Catholic helps facilitate my connection with God and the communion of saints: the ones who love God and love their neighbor, not just with nice words, but with concrete actions.

Maybe one of those distant ancestors of mine are part of this community too.

Sign up with your email or follow me on Twitter or Facebook to keep up with new posts.