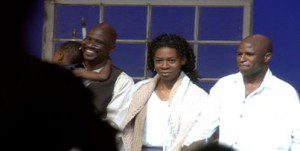

I think I slept for a month after the first production of I Am Jane. I was completely exhausted. I was the playwright, costume designer, set designer, and director of this play about black Mormon pioneer Jane Manning James. I have since learned to delegate.

We filled the chapel and more for that production, and in some ways it marked the time when the Genesis Group got big and started getting attention. In the audience was one of Jane’s descendants, who had already labeled the play “scurrilous.” She had said she would never forgive the church for what it had done to her father, Monroe Fleming. (I don’t know fully what she meant by that.) I’m sure she hated the production, but I never saw her afterwards, and she died a year later.

Soon, we found another descendant, Louis Duffy, who was thrilled to join us in paying tribute to his ancestor. By this time, Tamu Smith was playing Jane and Denise was finishing her degree and getting married.

Tamu did the role for a decade, ceding it to Fiona Smith (who later portrayed Jane in the film about Joseph Smith shown in the Joseph Smith Building theater) during a pregnancy. With Fiona as Jane, we did the show in the Bountiful Regional Center, a church-owned site. We had to send the script through correlation, and met with someone from the committee who wanted a few changes–such as not referring to Elijah Abel as “Elder Abel.”

We performed the play several times at BYU, but it met controversy. One professor was concerned that his students might not be able to handle the discussion of the priesthood restriction, that they might start doubting the prophets.

Today is a new day, though. Once again, we are set to present the play at BYU, starting on Tuesday, February 25th. This might be our most important performance ever, and perhaps our last. Tickets ($3.00/person; $5.00/couple) are available at the WSC information desk, or by calling (801) 422-4313.

What follows is my playwright’s statement, which will be on all programs.

It is not easy to mount I Am Jane—especially at BYU. We have 265 students of African lineage at BYU, out of a 30,000 student body. Only a fraction of these 265 students have an inclination to be in a play, and of this fraction only a few can find the time for it. We have gone into the community to fully cast it, and each actor has given their time generously and without any compensation. Some have traveled from Salt Lake City to attend rehearsals.

With such difficulties, why would we attempt this play? Simply because it matters, and this year it matters even more than it has previously. On December 6th, 2013, the LDS Church released a statement about blacks and the LDS priesthood, approved by the Quorum of the Twelve and the First Presidency. It states:

Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.

No other justifications were given throughout history than those the church now proclaims as wrong. As the statement points out, the Church was restored in a time when race issues were strong. The Civil War was just around the corner. The Nat Turner rebellion happened one year after the Church was organized. Under Brigham Young, black servitude was accepted in Utah, and the priesthood restriction started. The Church statement contextualizes these actions thus:

At the time, many people of African descent lived in slavery, and racial distinctions and prejudice were not just common but customary among white Americans. Those realities, though unfamiliar and disturbing today, influenced all aspects of people’s lives, including their religion.

Jane Manning James is mentioned specifically, along with Elijah Abel, in the statement:

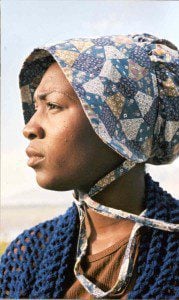

[A]t least two black Mormons continued to hold the priesthood. When one of these men, Elijah Abel, petitioned to receive his temple endowment in 1879, his request was denied. Jane Manning James, a faithful black member who crossed the plains and lived in Salt Lake City until her death in 1908, similarly asked to enter the temple; she was allowed to perform baptisms for the dead for her ancestors but was not allowed to participate in other ordinances.

Consider that Jane approached every church president from John Taylor to Joseph F. Smith to receive her temple blessings. We have copies of the letters she dictated asking poignantly for these ordinances: “I realize my race and color and cannot expect my endowment as others who are white. Still, inasmuch as this is the fullness of times and through Abraham mankind may be blessed, is there no blessing for me?”

It is beyond dispute that Jane was loved by those who surrounded her, including by those church leaders who denied her requests. President Wilford Woodruff received Jane into his home on several occasions. He blessed her for her faith, but recorded in his journal that he could not give her what she wanted:

Oct. 16, 1894: We had meeting with several individuals among the rest Black Jane wanted to know if I would not let her have her endowments in the temple, this I could not do as it was against the law of God as Cain killed Abel all the seed of Cain would have to wait for redemption until all the seed that Abel would have had that may come through other men may be redeemed.

As the playwright and one who has become devoted to Jane’s story and its implications, and has been blessed with the friendship of one of her descendants, Louis M. Duffy (who donated the material on display in Special Collections of the HBLL), I have thought how different BYU might be today had the idea of Cain’s curse been disavowed before the Saints came west. It is a fleeting fantasy, though, because we are where we are in 2014. Therefore, what is our responsibility towards those who constitute the only group of Latter-day Saints who were specifically designated as “cursed”? Now that we understand that the idea of a curse was a remnant of 19th century thought, how do we move forward and invite all to “the welcome table”?

Everyone in this play hopes that it will inspire the empathetic imagination in all who see it, that all may be edified and also challenged. Jane’s faith, which saw beyond any racial distinctions, should mentor our faith. When Elder David B. Haight dedicated the Jane James monument in 2000, he said that he knew Jane had taken care of his ancestors, who were in her pioneer company. He knew this, he said, “because that’s the kind of person Jane was.”

How can we “take care” of Jane’s progeny and others who need access to education, job opportunities, and a glorious vision of their divine nature and eternal possibilities? This is a personal question, one for each audience member to ponder.

We gratefully acknowledge that we as a church have come far from where we started from. As our closing musical number says, “Nobody told me the road would be easy. I don’t believe He brought me this far just to leave me.”

May we commit ourselves to doing all we can to become fully unified as the body of Christ, and to listen to one another’s stories—including the hard parts—with open hearts.

(The Church statement is found here: http://www.lds.org/topics/race-and-the-priesthood?lang=eng )