As a member of a coterie of journalists who cover religion, I have been confounded by the moralizing in print this presidential election season has elicited from journalists and thought leaders. Christian journalists and pundits have either struggled to reconcile their finely-tuned moral sensibilities with a morally ambivalent candidate or they haven’t struggled at all about it and have instead called down unequivocal condemnation and scorn.

Are Christians obliged to condemn moral imperfection of secular governing authors? Are they remiss if they support those who are morally imperfect? These are the questions of the ages.

I have been helped, both as a journalist and a person of faith, in finding a helpful way to view the acts and misdeeds of great leaders while at the same time, understanding that God (if we believe he is operative in this arena) does not see as humans see and does not judge as humans judge. And we in the media would be well-served to bear this in mind as we cover these tumultuous times.

I have come to this understanding by scrutinizing the life and misdeeds of one of the Bible’s most notable “heroes,” who, in addition to single-handedly consolidating the newly formed “kingdom” of the nation of Israel through warfare and who likewise committed two great sins — murder and adultery — was also deemed “a man after God’s own heart” (1 Sam 13:14).

I am referring to David — “the-Bible-hero” who picked up five smooth stones from the river bed and confronted the bully giant Goliath, flung the stones from his sling and hit him between the eyes, felling him. The young shepherd knew the stones’ size and weight, the rate of trajectory, the force with which they would find the target. He leveled the giant when everyone else, including his brothers, curled their tails and ran in retreat. But this heroic David is not what made him the man after God’s heart.

That would be another David whose true nature is laid bare in an interesting list noted in 2 Samuel 23:8–39. This list denotes a contingent of warriors who have been called King David’s Mighty Men. The text divides these men first into a group of “Three” and then “Thirty.” (It should be noted that there are more than thirty on the list.) One name on that list, noted last, opened my eyes to understand why David could have done the things he did and still be “a man after God’s heart.”

The name is that of “Uriah the Hittite.” He was Bathsheba’s husband who David, after an illicit affair that impregnated Bathsheba, put on the front lines of battle to ensure his demise. Being tacked on at the very end of the list of the Thirty Mighty Men gives it a peculiar feel, as if the scribe hadn’t planned on including him at all, as if he stuck the name at the end as an afterthought. Including Uriah’s name on that list, after all, would stand as a permanent reminder of the darkest part of King David’s heart and a testament to how low he was willing to go to cover his shame. David killed one of his best men, one of the Thirty.

Maybe at first the scribe had wanted to erase Uriah from the record, the way David erased Uriah from life. Maybe David saw the name was missing from the list and said to the scribe, “Where’s Uriah?”

“Uriah?” the scribe might say. “You want me to include Uriah?”

Maybe the scribe scribbled the name in disgust, loathing his king for the treachery associated with that name. Or maybe tears fell from his face onto the page as he scribbled it. Anyway, Uriah’s was the last name entered into the permanent record of David’s mighty men, and this much we know: If his name appeared, David wanted it there.

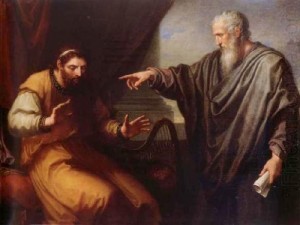

How could he not include it? David knew before God what he had done and the treachery that resulted — and everyone else knew it too. Nathan the prophet had confronted him about his crimes and David said, “You are proved right when you speak and justified when you judge.”

While we might tend to think that the giant-felling David is the one who won God’s heart, I demure. The man after God’s heart would be the David who told the scribe to put Uriah’s name on the list. Before God David knew it belonged there. And though he robbed Uriah of everything else, he would not rob him of his name, his legacy. For all his self-serving and truly heinous crimes, David understood that Uriah belonged on that list, regardless of the shame it would carry for himself by being there.

What is in a man’s heart is the true measure of his character, even when he (or she) may have many stains to answer for. Paul wrote to the Corinthians, “If I must boast, I will boast in the things that show my weakness.” [2 Cor.11:30] Uriah’s name on that list was David’s boast of weakness. That is how he could do the things he did and still be the man after God’s heart.

It reminded me of Graham Greene’s whisky priest in The Power and the Glory: “They had a word for his kind–a whisky priest–but every failure dropped out of sight and not out of mind: somewhere they accumulated in secret–the rubble of his failures. One day they would choke up, he supposed, altogether the source of grace.” David did not hide his shame nor revile his Creator. David’s life is a record of one heroic deed followed by a despicable deed, followed by turmoil, betrayal, and loss, followed by searching for God, finding him, ever searching, ever falling, ever finding.

It is a complex, messy picture and one that captures everything about the human story. All of us who grapple to interpret the current times in its dissonance and tumult would do well to remember it.