Today is the Feast Day of Saint Francis, which in the Catholic tradition, is the day to remember and celebrate the life and death of the saints. Francis died on this day 791 years ago, in 1226 after many years of contending with various debilitating illnesses. His final weeks are referred to by locals in Assisi still as sua agonia (his agony).

Today is the Feast Day of Saint Francis, which in the Catholic tradition, is the day to remember and celebrate the life and death of the saints. Francis died on this day 791 years ago, in 1226 after many years of contending with various debilitating illnesses. His final weeks are referred to by locals in Assisi still as sua agonia (his agony).

As a Protestant, I derived great spiritual consolation from Saint Francis during a time when I was bereft of hope and inclined toward despair. (I have written a book about him: A Mended and Broken Heart, the Life and Love of Francis of Assisi if you are interested in a journalistic nonCatholic interpretation of his life.)

I can’t say specifically what it was about this saint that so affected me. But during my first visit to Assisi many years ago, I experienced consolations that I cannot account for in earthly terms. The singular question that pressed in on me at the time was, How does one finish a life with wounds?

Francis had been a happy youth, born in 1182 in the medieval fortressed city-state of Assisi, sprawled along the southern slope of Mount Subasio. He was the son of a wealthy cloth merchant, Peter Bernadine, and his French wife, Pica.

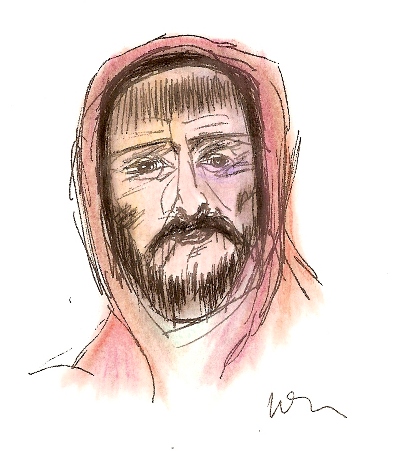

He was a little short, with large kind eyes, bearded, and had delicate hands and a frail physical constitution. Francis was known to sing songs of the Troubadours– French poets who traveled the countryside making melodies of the love’s longings. He apprenticed his father in the cloth business, happily assuming the role of model and trend-setter for silks and velvets of extravagant colors. His friends, when they’d been drinking, which was often, called him “our dominus” — our king. The appellation endeared Francis, and he would sing for them in French and buy another round of drinks. He was the leader of a “wild pack of Assisi youths,” as one historian puts it. Even so, Francis was well-liked. His extravagant generosity and courtesy extended to all, including the poor.

At the age of 20 Francis had fought with Assisi in a local battle against neighboring Perugia, and his hometown warriors were slaughtered. He himself was taken prisoner in Perugia where he languished for a year underground with little food, bad water, cold conditions, and no latrine and contracted malaria that would plague him the rest of his days. His father negotiated a ransom for his release. Francis remained bedridden for a year in recovery. He was never the same.

At the age of 23, while on an errand for his father, he passed a run-down church a mile south of Assisi called San Damiano. He stopped to rest inside the crumbling walls. Francis reposed beneath a Syrian cross hanging over the altar bearing the image of the crucified Christ. He perceived the image was speaking to him. “Francis,” it said, “don’t you see that my house is being destroyed? Go, then, and rebuild it.” This began what would become a protracted but life-shattering conversion of Francis, emulating Christ in humility and poverty.

During that first visit to Assisi, on our last morning, I made my way alone in the early light down to that little church. It was here where Francis had retreated near the end of his life when illness and blindness had nearly incapacitated him. He lay day and night in a hut tended to by his female companion, Clare, unable to endure sun or firelight.

I found a spot under a tree behind the church near a cistern, the morning’s light glinting off the olive trees wet from dew. I thought of Clare, whom Francis had brought here. Some say they’d loved each other but had renounced it. The life of Francis was a love story in any case. I thought of the question I had put to Francis in my imagination — How does one finish a life with wounds? I heard nuns singing from inside the walls — the same walls Francis had built when the voice said, “rebuild my church.” He had been given a task. He accepted a humble responsibility. From that church where I sat, the image of the crucified One brought him purpose and rescued him. So he picked up a stone.

He was a pilgrim, stripped of the life’s consolations. Life as a pilgrim had but a single purpose: to have eyes to look for the unexpected, to imagine possibilities, and to remain accessible to the voice that speaks. He heard it and picked up another stone. When he could find none, he begged for stones. Stone upon stone, amid olive groves and singing birds, cooled by morning mists, he moved and moved and piled and scraped until the stones became a wall. The wall became a church. The church became an assertion.

At the end of Francis’ life, age 44, his liver and spleen were distended with lesions. Malarial parasites made him vomit. He found it hard to breathe. The paradox was, even in suffering, his death became an assertion. God acted always only in love. He made a request of his brothers as his final gesture on this earth: “When you see that I have come to the end, put me out naked on the ground and allow me to lie there for as long as it takes to walk a leisurely mile.”

They lay him naked, face down, and he embraced God’s beauty in the dirt. He remembered his dependence on God alone. He whispered to a brother, “I have done what is mine to do. May Christ teach you what yours to do.”

How does one live out a life with wounds? Pray open-armed, for the One who hears also stretched his arms wide. And move stones.

![]()

Please check out my new Patreon page that includes contemplative and devotional readings on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.