For some time now, I’ve been thinking a good deal about the importance of cultivating the virtue of fortitude as a dimension of spiritual formation in the modern seminary. The spread of Covid-19 has added focus to that reflection. Many clergy have waded into the challenges posed by this pandemic and have provided solid leadership for their congregations. But, at the same time, a vocal handful have publicly rehearsed how stressed and disillusioned they are by the demands that it has made upon them. When problem-solving shades off into what can only be called handwringing, I find myself asking what has been missing from clergy formation, and the answer, I believe lies in part with our failure to cultivate spiritual virtues.

There was a time when one didn’t need to wonder. In the ancient world conversations about virtue were a commonplace. Classical antiquity teamed with reflections on the subject, including the work of Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Marcus Aurelius. In the church the same subject occupied the thoughts of Ambrose, Augustine, and Dante, among others. And the cultivation of a virtuous life or “purity of heart” was the underpinning of monastic life. But with the advent of utilitarianism and deontological ethics the conversation about virtue slipped to the margins of both theological education and philosophy.

In the modern Protestant seminary that conversation was further sidelined by a number of other factors as well. Seminaries are not, for example, deeply invested in the task of cultivating virtue because it is the church that assesses the character of those in the ordination process. Seminaries, if they deal with formation at all, take no ownership over the process, except at the extremes. In addition, seminary faculties are now so divided over their view of what is essential to theological and spiritual formation that coming to any kind of agreement on the virtues needed would be hotly debated.

As a result, where virtues – and fortitude, in particular – receive any attention today, it is discussed in largely therapeutic categories under the label, “grit.” In that regard, Angela Lee Duckworth, a professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania, is one of the leading voices. Duckworth is convinced that “grit,” which she defines as “passion and perseverance for long-term goals,” is the key to achievement. One summary captures the theme of Duckworth’s “science of grit”: talent x effort = skill, skill x effort = achievement.

In one way, Duckworth’s “science of grit” is the most one can expect as far as the public conversation about fortitude is concerned. We live too far from the conversation about virtues to expect society to reinvigorate the conversation that shaped the ancient and medieval church. And, as the modern west becomes increasingly alienated from its Christian roots, it also becomes increasingly difficult to reassemble the culture and vocabulary of the world in which the conversation about virtue once held sway.

However, the contemporary conversation is far from the same as the church once nurtured. For Duckworth’s “grit” is something one cultivates in the name of achievement. It is a means to an end. And her framework for assessing the way in which it is acquired and the advantage it accrues is entirely therapeutic. To be sure, she keeps open the possibility that one’s passion and perseverance could be focused on God or religious goals, but that is only one form of achievement among others.

The conversation about fortitude in the context of the Christian faith is entirely different: Fortitude in that context is about steadfast devotion to the purposes of God, regardless of life’s circumstances.

It cannot be cultivated. It is the resolve that arises from a life-changing conviction about the meaning of life, the nature of the world, and God’s will for both. It deepens as that conviction takes root in the Christian’s life, and achievement – as such – is beside the point.

Fortitude is, instead, about becoming and being someone who is reliably available to the purposes of God and acts in spite of one’s fears. It is not, however, about a blind impulse, bent on doing whatever one chooses to do. Fortitude is informed by a sense of justice or what might be described as the mind of God, which can only be grasped by becoming more deeply acquainted with God; and it is also disciplined by prudence – “the charioteer” of the virtues – which leads the Christian into a measured and prudential use of energy.

To be a bit more concrete, then, what would leadership informed by fortitude look like in a time of pandemic – or at any time, for that matter?

One, it requires a leader who has deep spiritual commitments of their own.

When the circumstances of life strip us of every resource and skill that we typically depend upon, we are forced to draw on our formation and the elemental commitments that prompted us to embrace the work that we are doing in the first place. Those commitments are of perennial importance. They are the commitments that keep us from being drawn off center. The commitments that keep us from dangerous forms of compromise. The kind of commitments that keep us from making decisions that opportunistic and pragmatic, rather than decisions that are spiritually and theologically grounded. If there is a difference in times of crisis, it may be the clarity such occasions afford. But our commitment to Christ and to the body of Christ are at the heart of our vocational lives and there is no other good reason for doing this work.

Two, it requires a leader who does what needs to be done.

Far too often we make the assumption that ministry is about what we want to do and the dreams that we harbor. Those dreams can be helpful in framing what we might do and what we might accomplish. It is also helpful to test those dreams against the body of learning that we acquire as we prepare. But we can be tied too tightly to the words of Frederick Buechner, “Your vocation in life is where your greatest joy meets the world’s greatest need.” Frankly, sometimes the needs of the world are what they are, and our great joy is beside the point. In the final analysis, spiritual leaders need to take their cues from the circumstances that confront their congregations.

We might dream of being great teachers or life-changing teachers. We may hope to alter some part of the social landscape and provide leadership for transformed communities. And certainly, we can and should work toward making those contributions and others. But effective leaders cannot overlook the basic and specific needs of a congregation and the fortitude it takes to meet those needs: Lifelong formation, attentive pastoral care, presence during crises, administrative oversight, the development of lay leadership, and stewardship of parish finances – to name just a few.

Three, for that reason, leadership in a time of pandemic requires a leader who might be disenchanted, but is not disillusioned.

A disillusioned leader works from dreams and aspirations that they refuse to surrender. Forged in a vacuum, they insist that the circumstances of their ministry match their expectations. “This is not what I signed up for” is the mantra of the disillusioned leader; and if their expectations go unsatisfied, they look for new opportunities. By contrast, the disenchanted leader may begin with the same hopes and aspirations, but possesses the fortitude to reassess those dreams against the demands of ministry. That process allows the disenchanted leader to let go of magical assumptions and respond as needed.

Becoming that kind of leader is, of course, a perennial challenge and fortitude is the key to becoming that kind of leader. “This is not what I signed up for” is what disciples of Jesus have always said, beginning with the first twelve. But that realization underlines the importance of fostering an environment in which greater attention is given to spiritual formation and with it, the cultivation of spiritual virtues.

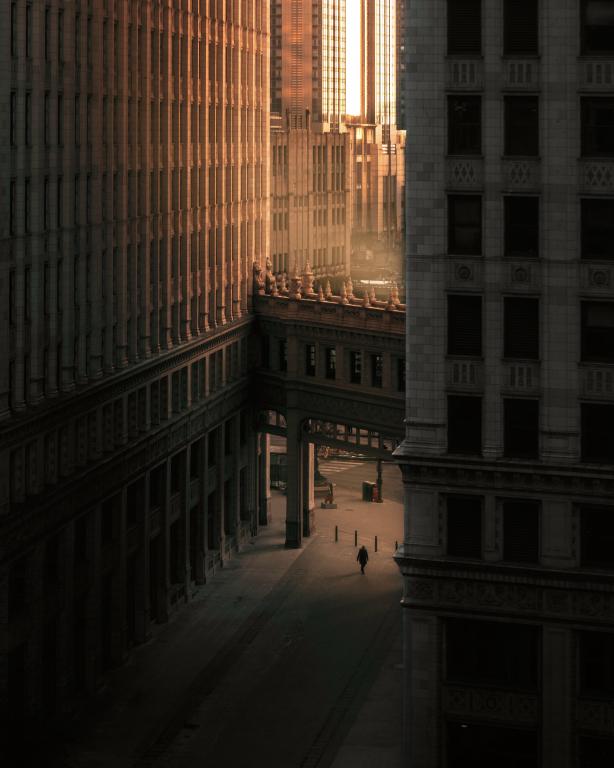

Photo by Benjamin Suter on Unsplash