The General Convention of the Episcopal Church is over, and it ended with a decision of greater significance than one might have expected from a meeting truncated by Covid 19. In two sessions, the first of which was marked by both confusion and a lack of clear definitions, the House of Bishops eventually passed resolution A059 which was approved with minor revisions from the House of Deputies. The pivotal conclusion was this:

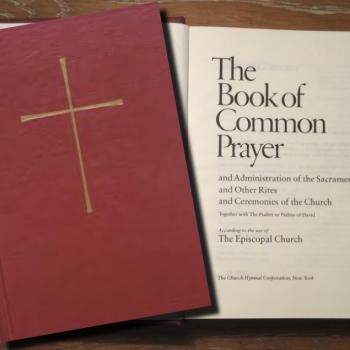

A059 would, for the first time, define the Book of Common Prayer as “those liturgical forms and other texts authorized by the General Convention.” In other words, liturgies that are not in the current prayer book – such as same-sex marriage rites and gender-expansive liturgies – could be elevated to “prayer book status,” whether they are replacing parts of the prayer book or standing on their own.

At Convention and online, conversations ensued about what constitutes “a book”, how books are amended, and what it means to talk about a book in the digital age. But that all seemed to be a bit of an afterthought, given the absence of clear definitions and the sheer confusion that dominated the first session.

What seemed to be of more immediate concern was the desire to get Prayer Book revision going, in spite of the complexity entailed in its revision. One reporter observed:

[Bishops] Lee, Doyle and Hollingsworth had encouraged the house not to delay acting on A059 or referring it back to another body because of the timing requirements for constitutional and canonical changes, which Bishop Sean Rowe, the House of Bishops’ parliamentarian, explained.

“Let’s say we do pass it in 2022 and in 2024, [new] canons are ready to go,” he said, describing the ideal scenario. “If we [don’t pass] it here, we can’t do anything with it until 2027. So, it’s the difference between doing something in two years or waiting six years.”

That conviction led to a welter of activity over the space of two days, and even after the vote was taken, there were Bishops raising questions about the working assumptions behind the decision.

But this much is clear: the decision taken spells the end of common prayer. There will be those who will differ. They will argue that the BCP did not dictate a common prayer and already offered a variety of options. They will argue that the process of authorization had created realities that had further compromised the concept of common prayer; and there are those who will argue that it is old-fashioned to think about “books” as physical objects with covers and pages. Indeed, all of those arguments appear to have been offered by some of the bishops in defense of the resolution.

But it isn’t the Prayer Book as a physical object that is at issue, of course. What is at issue is the content of the Prayer Book, and in a church that has long argued that the Prayer Book is where we do our theology, content matters.

It is for this reason that the decision that the Convention made is of such consequence. The bishops could have worked to rationalize their practice of authorizing liturgies. They could have found clarity around what they mean by “trial use” or they could have done a deep dive in exploring just what the digital age has done to the concept of a book and the way in which those changes impinge on what is considered the content of a book like the BCP. They could have tabled the Resolution for further study. Instead, they have radically changed the way in which we will think about our liturgy going forward.

So, here we are, and it is important to think about the consequences:

One, The Book of Common Prayer no longer occupies the definitive place it has held in our tradition. Yes, the BCP is what it is by consent of the General Convention, but once the Book of Common Prayer was approved as such, it occupied a unique place in our liturgical and theological traditions and its alternation was conditioned by a lengthy process. The latest decision de-centers the BCP, making what the Convention approves which is “out there” and “resident on the web” the reality in which the BCP takes its place. One can argue that this place in our tradition is unique. One can argue that it benefits from its history and the process that brought it into being, and it has been “memorialized.” But one cannot argue that its position is unchanged, and memorialized has a different ring to it now – as something from the past, encased in amber.

Two, the content of the BCP will be further relativized by subsequent Conventions. The House of Bishops favored the process by which changes were made at this Convention because it shortened the timetable for liturgical change. Having defined the church’s liturgy as practices approved by General Convention, it is no longer necessary to abide by the process required for changing the BCP itself, and it will be impossible to resist the temptation to make further changes without confronting the challenge or Prayerbook revision.

Three, there will never be another printed Prayerbook. The resolution passed at Convention was also driven by the realization that the amendment of the book itself would take too long, that the majority of Episcopalians were opposed to its revision, and that – in any event – parishes cannot absorb the cost of buying new books. That situation will not change.

So, having declared that what is online has the same status as the BCP and – given the fact that the BCP has already been digitalized, – the online resources will now prevail. It will be a small thing in the next Convention or two to declare the print version a relic of the past and, in turn, declare the electronic reality the one and only resource for liturgy.

Of course, there are many who will welcome this development. In one conversation I had about the sacraments, a priest observed: “God did not ‘invent’ sacraments. We, the people of God, did.” From start to finish those assumptions fly in the face of the convictions that have shaped the church’s sacramental theology. Historically, the church has considered the sacraments as the work of God in Christ, the full nature of which is revealed to the church by the Holy Spirit.

Human beings are involved, of course, in listening, in discerning, and in crafting the language of the sacraments. Christianity is an incarnational faith. We do not believe that the will of God is given expression on golden tablets dropped from the sky. But the church also believes that prayerful discernment reveals insights into the will of God that are given expression in our liturgy and which make demands upon the church, her clergy, and the laity.

To argue that “we, the people of God, invent the sacraments” sweeps away those assumptions and places the church’s liturgy completely at our disposal. We “take” communion, we don’t “receive” it. We “invent” the sacraments, God does “give” them to us and “invest” them with power. Liturgy is “the work we do”, rather than the “work we are given”. An endlessly malleable Prayer Book will appeal to that mindset. But that mindset will change our eccesiology as well.

We were – up until now – a church of “ancient mysteries and modern faith”. But now we are a church of rituals that we have crafted. Rituals not just without covers but without boundaries or shared content – practices that can be modified by an agreed process. But if it is that human a process, when will people decide that even the process has no claim upon us? I am afraid that this sends us inexorably on the course that leads to each individual its own church, its own polity, its own liturgy, and ultimately its own gospel.

Photo by Erika Fletcher on Unsplash