Who are you?

Deep into life identity is a challenge for all of us. I don’t know anyone who escapes that challenge. And for many people it is a source of real struggle and no small amount of anxiety deep into life.

Identity is also a challenge that reinvents itself. Even after we have made the choices that most of us identify with settling into adulthood – finding a spouse, getting a job – the questions of identity surface and resurface.

There are endless reasons for this struggle. Insecurity is part of the struggle – the differences between what we assume we will be doing, and the reality itself – perfectionism that holds us to a standard we can’t fulfill – changes in fortune, including job loss, illness, and even retirement.

This endless quest for significance can also engender insecurity. After I lived and worked in Washington for a time at the National Cathedral, I told a friend, “No one in this town wants the job that they have. Priests want to be Deans of Cathedrals, Cathedral Deans want to be Bishops. Congressmen want to be Senators and Senators want to be President.

But – in ways that are profoundly destructive – I think it can also be argued that the struggle with identity has become the defining struggle of the late 20th and early 21st century, particularly in the so-called developed world. There are a number of factors that are driving this development.

One has been the extent to which post-modern assumptions have undermined the confidence that there are any God-given characteristics to life. Arguing that identity is endlessly malleable and entirely in our control, our culture post-modern philosophy suggested that there is nothing so basic to our being that we cannot reinvent. And – in so doing, has burdened us ways that we don’t yet appreciate. But rising suicide rates, surveys that measure basic happiness, and the social dislocation that messaging of this kind has helped create suggests that we are headed no place good.

Our prosperity and isolation from one another is a second factor. The only thing worse than being told that your identity is entirely up to you, is being told that you have all the time available to you to devote to that task. Done in isolation from others and without an obligation to help or care for others, the notion that life’s task is self-definition is – in and of itself – crazy making. The supposedly endless choices, the absence of guidance or feedback and the absence of an obligation to care for others constitute a dangerous cocktail of loneliness.

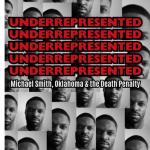

The third factor is social media. Here me carefully here, I am not opposed to social media across the board, and I recognize the real value of the community that it offers us. But – as study after study demonstrates – without grounding in flesh and blood relationships and spiritual balance that equips us to test the value of what we find there, social media can focus the other dynamics I have mentioned destructive force. Bullies who once inflicted pain on one or two other people can now attack and isolate hundreds of people. Profiles can be edited to suggest that certain ways of living and behaving can be pursued without consequences. And people who already struggle with their own self-worth can be reduced to ash.

The American Psychological Association notes that “using social media is not inherently beneficial or harmful to young people.” But studies have shown that “nearly 2 in 3 adolescents are ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ exposed to hate-based content on social media.” There is a measurable “connection between social media cyberbullying and depression among young people.” And “teen girls and LGBTQ youth are – in particular – more likely to experience cyberbullying and online harassment.”

These issues have been on my mind this Advent. And they were front and center when I preached on John the Baptist this year (Jn 1:6-8, 19-28). The lines in Fourth Gospel about John might seem to be a long way from the modern quest for identity, and in one way, of course they are.

The priests and Levites are trying to sort out why John is calling people to repent and baptizing them. They are trying to sort out how his ministry fits into the varied schemas of ancient prophetic hope and expectation. And – in the midst of a volatile religious climate – they are trying to sort out what, if any claims John may be making to Messianic authority. And John responds to those questions, distinguishing his own role from the Messiah and the difference between his baptism and the baptism that Jesus will eventually make possible.

But in the season of Advent, when we are rightly attuned – not only to the promises of God – but to the state of our own lives and hearts, I think it is also worth attending to the way in which John arrived at his own sense of identity. The assumptions that guide him, I think, provide an antidote to modern, post-modern confusion we experience on the subject.

For the sake of clarity, let me describe what grounds John’s sense of who he is, as two guiding principles:

The first principle is the most basic: John knows who he is because he belongs to God.

The difference between a world with God and a world without God is as basic a difference in world view that there is. And there is a world of difference between belonging to God and being without God.

In a world without God, identity is perpetually up for up for grabs. There is no point of reference beyond ourselves and beyond the judgment of others. One can either live a life in perpetual fear that we are not what we should be and endlessly open ourselves to the opinion of others – or we can resist the world’s criticism by simply insisting that we can’t possibly be wrong.

But when we navigate life without God, there is no way of being certain of who we are or why we are here; and – even if we can carve out some temporary certainty about who we are and what we stand for, there is no future beyond the grave. This is why the “new atheists”, unlike the old atheists, have been at pains to argue that there is a biological and evolutionary reason for morality. It is not easy to live with the conviction of atheists like Nietzsche that there is nothing in the world that matters except the will to exert power.

But when we say that – like John – our identity is grounded in the knowledge that we belong to God, it is also important to remember what this means. It is not about life on a knife’s edge or about getting our performance right: following commandments and avoiding sins.

Without suggesting that the commandments aren’t important, the far more basic choice is one of belonging to God, of being in relationship with God. And God’s desire and longing is focused on nurturing that relationship with us. Our understanding of who we are and how we should live flows from that relationship.

The second principle that guides John is that he finds his place in God’s work.

When we ask ourselves, what is God’s will for me, more often than not we ask ourselves, “What does God want me to do?” And that is a natural way of framing the question.

But in the history of the church’s spiritual quest, the prior and more important question is, “What is God doing?” In fact, that question is at the heart of the spiritual practice that the church calls “the practice of discernment”.

When John – and later, the disciples – asked themselves who they were in the “economy” or “work” of God, they first asked themselves what God was doing in and through Jesus – what God cared about, what God was trying to accomplish, and what place they were assigned in God’s work. And on that basis, they prayed about how they could contribute to what God was doing.

To understand ourselves as participants in the work of God has important implications that are visible in John’s responses to his detractors:

- It means that our sense of self-worth is grounded in God’s love for us.

- It means that there is never a time in life when we are without a contribution we can make.

- It means that we are available to do what God needs for us to do.

- We aren’t worried about our status.

- And we are untroubled by the opinions of others.

This realization frees us from the exhausting and futile task of inventing ourselves and of justifying the choices that we make with our lives. It also frees us from the relentless, inner voice that says, “you are not enough”. To put ourselves at God’s disposal is to realize that each of us is God’s gift to the world in the making. And that is a rich, life-giving, and productive place to live that stands in sharp contrast to being robbed of that love and acceptance.

During this season of reflection and prayer, I hope you have embraced your relationship with God. Let that relationship and God’s work in the world shape your efforts. And spend some time asking yourself who you are in God’s presence. Let the results of that prayer strengthen and guide you in the future.