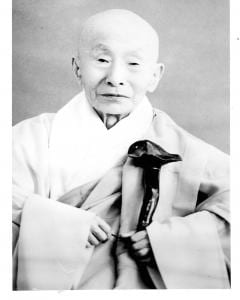

“When you truly understand this fundamental principle you will not be anxious about your life and death. You will then attain a steadfast mind and be happy in your daily life. Even though heaven and earth were turned upside down, you would have no fear. And if an atom bomb went off, you would not quake in terror.” – Yasutani Rōshi (1)

When I read those words in 1977, they seemed so outrageous that I immediately sought out a teacher, and became a Zen student.

In this fourth post in the series, I’ll present and then briefly comment on Dàhuì’s third theme, “You must assume a stance of composure.” In addition, I’ll fill in some background on how Dàhuì cultivated the keyword method with his first student who realized kenshō, significantly, the nun Miàodào.

First, the usual series introduction and disclaimer:

In the recent translation of The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pujue, translators Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe offer nine themes, motifs, that emerge in the letters about how to do keyword practice (話頭 huàtóu, Japanese, watō). I’ve been sharing them on the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training for students working with keywords, and I’ll also be sharing them here for others who might be interested. Close study of an ancient text can help both students and teachers notice details of the method and refresh their practice spirit. If you are working with a keyword with another teacher, consult with them, of course, and rely primarily on their guidance.

Two entries: principal and practice

A sidebar from Bodhidharma’s Two Entrances:

“Now, in entering the path there are many roads. To summarize them, they reduce to two types. The first is entrance by principle and the second entrance by practice.”

Dōgen was all about principle (理 or “inner pattern”). Pick up the Shobogenzo almost anywhere and you get the inner pattern through a firehose. Dàhuì was clearly a practice guy (行, practice, doing, religious acts, deeds, or exercises, aka, method). He focussed on a refining a method for helping people realize kenshō by arousing Great Doubt and skillfully employing the keyword (e.g., mu). Throughout his career he seems to have continued this inquiry, modifying his teaching practice based on experience.

So principal and practice are two entries. One of them isn’t better than the other. Think two foci in intimate dialogue. Some of the great teachers were more inclined toward one of the gates than the other, due to their personal proclivities, and the needs of the times.

A woman does it again (and gets little credit)

It might help at this point in this series to offer a little more context about the development of the keyword method. I mentioned in a past post that Dàhuì was uncommonly devoted to householder and women practitioners. In fact, early in his career, he refined his keyword method with a nun, Miàodào, who first studied under the Cáodòng (Japanese, Sōtō) master, Zhēnxiē Qīngliăo (1088-1151; Japanese, Shinketsu Seiryō, aka Choro Seiryō, an ancestor in the Sōtō lineage that continues today).

In fact, Miàodào left a summer retreat with Qīngliăo – a really big deal – in order to train with Dàhuì. The fact that Dàhuì accepted a run-away nun reflects his characteristic lack of concern with being polite. He even made a vow, “Even if this body of mine is pulverized into minute atoms, I will never compromise the buddhadharma to accommodate customary etiquette.”

Turns out that Miàodào is the one person from whom we have recorded teachings translated into English (as far as I know) that studied with both Qīngliăo and Dàhuì. She said that she learned from Qīngliăo, also an inner-pattern type, that enlightenment was not an event. She learned from Dàhuì that, indeed, it was. This distinction is still present in the just-sitting and kōan introspection circles today. And both, of course, are correct. Again, rather than right and wrong, think two foci in intimate dialogue.

When Miàodào left the practice period with Qīngliăo, she joined a group of 70 practitioners, meeting one-to-one with Dàhuì twice every day. And even though Dàhuì had been teaching with intensity for several years, Miàodào was the first to realize kenshō.

Here’s Dàhuì talking about his work with Miàodào:

“I raised [for her] Mazu’s ‘It is not mind, it is not Buddha, it is not a thing’ and instructed her to look at it. Moreover, I gave her an explanation: ‘You must not take it as a statement of truth. You must not take it to be something you do not need to do anything about. Do not take it as a flint-struck spark or a lightning flash. Do not try to divine the meaning of it. Do not try to figure it out from the context in which I brought it up. ‘It is not the mind, it is not the Buddha, it is not a thing;’ after all, what is it?

“…One day…she got a moment of joy. She soon wanted to come to spit out [her understanding]. I saw that she wanted to open her mouth and shouted ‘Ho!’ and said: ‘Wrong! Get out!’

“Why? Because I saw that what she had was not the real thing. For her heels had not touched earth. In this kind of moment, even though she had a moment of joy, as it says in the [canonical] teachings, ‘in front there is no new realization, and if one goes back, one has lost the old residence.’

“The old cave hole had already been torn down by me, but in front of her there was no dewelling to live in. When one reaches this point, for the first time there is no gate through which to advance or retreat.

“After a while she came again, bowed, and said: ‘I really do have entrance.’

“You could say that I coddled her like a beloved child. I stopped blocking her path and opened up a path in front of her. I asked her: ‘It is not mind, it is not a Buddha, it is not a thing. How do you understand this?’

“[She] said: ‘I only understand this way.’

“Before the sound of her words had died out, I said: ‘You added in an extra “only understand this way.’

“She suddenly understood. In the several years since I became a head seat and took up teaching, she was the first [of my students] to succeed in investigating Chan.”

Here’s Miriam Levering commenting on this:

“The very earliest example of Dàhuì’s [keyword] practice instruction in general and of his standard instructions in particular is thus this set of instructions to Miàodào. Miàodào’s success with these instructions must have been significant in confirming what became Dàhuì’s characteristic approach to teaching.” (2)

Miàodào eventually became one of Dàhuì’s dharma successors. And Dàhuì’s keyword innovation – honed through his work with Miàodào, and her diligent work with Dàhuì – swept through the Zen world faster than scholars can track it, like the proverbial arrow flying past Korea, and still stands as one of the greatest innovations in meditation practice since Buddha Shakyamuni.

You can thank a woman for that too.

(Finally) Theme 3: You must assume a stance of “composure”

Broughton and Watanabe: “The mental attitude required in general for [keyword] practice is composure. Letters of Dàhuì … stipulates that twenty-four hours a day the student is to “make themself composed.” The [keyword] practitioner is to be calm, quiet, leisurely, composed, and unhurried:”

Letter #20.2: “If you want to make suffering and joy indistinguishable, simply do not ‘rouse yourself to engird mind’ or ’employ your mind to quell delusive thought.’ Twenty-four hours a day make yourself ‘composed.’ If suddenly habit-energy from past births arises, don’t apply mental exertion to hold it in check. Merely, in the state where the habit-energy arises, keep your eye on the [keyword]: ‘Does even a dog have buddha-nature? No [wu 無].’ At just that moment [wu 無] will be ‘like a single snowflake atop a red-hot stove.’” (4)

Comments

1. “If you want to make suffering and joy indistinguishable,” that is, not to be tossed away by the 10,000 things, and see the unfolding of the buddhadharma through each and everything.

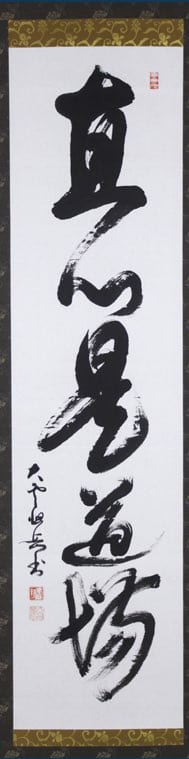

2. Practicing composure is really quite subtle in the manner that Dàhuì presents it with a couple near enemies. First, let’s look at the phrase that’s translated “composure.” It is made up of five ideograms (放教蕩蕩地), and includes the senses of being calm and poised, unbridled, unfettered, and grounded.

These five characters could be literally be translated like this: “let go of making the ground flutter.”

That is, be composed. How? In English, we might say “make yourself composed,” but the composure that Dahui is advocating is a form of nondoing, letting go of making the ground flutter.

Now about the near enemies. Dàhuì’s instruction first says “…do not rouse yourself to engird mind,” that is, do not encircle the thought/feeling of the moment with the keyword in order to contain or control what’s arising. The keyword can and usually is first employed to repress what’s happening so that the student might appear composed. Dàhuì, however, is encouraging the keyword student to be really composed. To let go of making the ground flutter. Don’t neglect this point!

Dàhuì also instructs, “Do not employ your mind to quell delusive thought.” Mu, for example, can be employed to quell disturbing thought/feeling. And it works! A wonderful discovery when a student begins diligent practice with a keyword and finds a new tool for their toolbox. And then the futility of the strategy sinks in.

Dàhuì describes this futility like this: “Even if their minds are temporarily ‘parked,’ it’s like grass with a stone pressing down on it—before you know it, it’s growing again.” (5)

Instead, a very important skill is to bring the keyword into the thought/feeling. Enfuse the thought/feeling with the keyword in the very place in the body mind where the thought/feeling is arising. Yes, let go of the focus on the tanden and even the hara.

“At just that moment [wu 無] will be ‘like a single snowflake atop a red-hot stove.’”

Notably, it is the keyword that evaporates! What happens to the thought/feeling – the red-hot stove? Investigate!

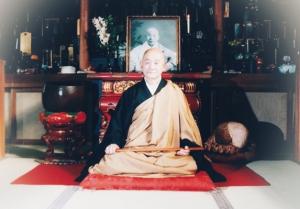

This post began with Yasutani Rōshi stressing how the mind post-kenshō is composed. Dàhuì emphasized that to realize kenshō, the mind must be composed. This kind of composure, letting go of making the ground flutter, is good at the beginning, good in the middle, good at the end.

(1) The Three Pillars of Zen, Rōshi Philip Kapleau, 86-87.

(2) The material on Miàodào and Dàhuì is from “Miao-tao and Her Teacher Ta-hui,” Miriam Levering, https://www.douban.com/group/topic/34099801/.

(3) The Letters of Chan Master Dàhuì Pujue, 58:4: Smashes perverse teachers.

(4) Ibid., “Introduction: Recurring Motifs in Huatou Practice,” trans. Jeffrey L. Broughton and Elise Yoko Watanabe.

(5) Ibid., “10.4: Fu has violated Dahui’s directive to avoid perverse teachings.”

Dōshō Port began practicing Zen in 1977 and now co-teaches with his wife, Tetsugan Zummach Sensei, with the Vine of Obstacles: Online Support for Zen Training, an internet-based Zen community. Dōshō received dharma transmission from Dainin Katagiri Rōshi and inka shōmei from James Myōun Ford Rōshi in the Harada-Yasutani lineage. Dōshō’s translation and commentary on The Record of Empty Hall: One Hundred Classic Koans, is now available (Shambhala). He is also the author of Keep Me In Your Heart a While: The Haunting Zen of Dainin Katagiri. Click here to support the teaching practice of Dōshō Rōshi.