James Myōun Ford Rōshi recently asked, “What would you say are the essential Dōgen texts?”

Below you’ll find my response as well as what I’d say (if he’d asked) about essential Hakuin texts.

But first, a word from Hakuin about the importance of study:

“I have always lamented Zen’s ignorance of the sutras,

Monks plodding ahead aimlessly like blind donkeys.

Even after kenshō, unless you know Buddha’s words,

You’re like a carriage only fitted out with one wheel.

And if you read the scriptures without having kenshō,

You’re only a parrot imitating someone else’s speech” (from Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn, 78).

I don’t want to pick an argument with Hakuin, but I’d say that study is also important before kenshō in order to till the field of the heart-mind, and show us, as Katagiri Roshi said, how stupid we are.

Caution: By the phrase “Zen study” I don’t mean sitting alone and reading Zen books. Zen study, in my view, is done in relationship with a teacher who is steeped in the way. Otherwise, study can simply be a way to stuff your head with buddha knowledge and, as such, can be used to solidify the defensive walls of self.

This kind of solo study is also likely to remain unintegrated with your project of cultivating awakening, and encourage spiritual by-passing. In addition, we large-brained primates have a way of hunting-and-gathering those tidbits that support our present view and dismissing those tidbits that don’t.

Zen study, on the other hand, undertaken in the context of the teacher-student relationship, offers the best way to embody text as Zen practice.

My list of essential Dōgen texts

I intended to limit my list to just ten fascicles, but in the spirit of Dōgen who modified the traditional “Ten Names of Buddha” such that it includes eleven names, I’ve settled on eleven texts. I went with those fascicles that would be most important for people new to Dōgen studies, not because I think that’s all that’s necessary. The first six in my list are mostly early Dōgen with an eye toward the actual practice and the last five are more from his middle period when he fully actualized his genius. Many other fascicles from this period could have been selected.

And truly, in my view, everything Dōgen wrote is essential. But that’s not what James asked. In what he did ask, I assume he meant “essential Dōgen texts from the Shōbōgenzō.” Other texts, Record of Things Heard, trs. Cleary (Zuimonki), Dōgen’s Extensive Record, trs. Okumura and Leighton (Eihei koroku), and “The Record Celebrating the Jewel,” see Takashi James Kodera: Dogen’s Formative Years in China, are also essential Dōgen.

One well-known text I don’t recommend is “Upright Cultivating Verification” (Shushogi), because it is a cut-and-paste, greatest-hits job from the late 1800’s. Granted it was (and remains) an important text for the Japanese Sōtō denomination, but because it doesn’t address zazen (no mention) or verification (one mention in the title), it is of limited use for students today.

Below I’ve used the Tanahashi English titles for simplicity and have added a brief comment about why I think the fascicle is essential. By the way, it’s always helpful to look at more than one translation and we now have several complete versions available. Here it is:

- “Guidelines for Studying the Way:” This is an early Dōgen text, written for his training students, and has ten essential points for practice, presented in a more rough and raw manner than fully cooked later Dōgen.

- “Universal Recommendations for Zazen:” One of Dōgen’s two meditation manuals. Indispensable for cultivating verification.

- “On the Endeavor of the Way:” This is also early Dōgen and wasn’t known widely until about 1800, 550 years after the old boy died, so although it didn’t play a role in 2/3’s of Sōtō history, it is widely read today. It contains the powerful and beautiful “Self Enjoyment Samadhi” section and eighteen Q&As.

- “Actualizing the Fundamental Point:” Also known by the Japanese title, “Genjokoan.” This short text is widely regarded as a summary of Dōgen’s extensive teaching. It ends with the “fanning kōan” that expresses the resolution of the young Dōgen’s question, “If we’re already buddha, why practice?” It also ends with a powerful Bodhisattva vow/call-to-action.

- “Instructions on Kitchen Work:” How to roll up our sleeves and put the “Genjokoan” to work in our lives.

- “The Bodhisattvas Four Methods of Guidance:” Giving, kind speech, beneficial action, identity action – written for householders and a compelling expression of how to take the practice from sitting to living.

- “The Point of Zazen:” This is the other fascicle devoted explicitly to zazen. Here Dōgen unfolds zazen as the “thinking, not thinking, non thinking kōan,” works through the sudden-gradual issue with the “polishing the tile kōan,” and then distinguishes earnest, vivid sitting (aka, shikantaza) and silent illumination by ever-so-politely reworking the great Hongzhi’s poem on zazen.

- “Great Practice:” In this fascicle, Dōgen brilliantly comments on the “wild fox kōan.” Essential for just-sitting and kōan-introspection Zen.

- “Prostrating to Attainment of the Marrow:” In this feisty fascicle, Dōgen most clearly expresses his view on the radical equality of the realization of women and men (and by extension, whatever other demographic divisions we might create). Of course, he also speaks to the importance of bowing.

- “Refrain from Unwholesome Action:” This is Dōgen’s unpacking of the three pure precepts from the perspective of non-doing (Chinese, “wu-wei”), so reflects the Taoist impact on Zen, and includes commentary on the “bird’s nest roshi kōan.”

- “Buddha Nature:” This includes thirteen kōans and Dōgen’s commentary with checking questions. It can be seen as a kōan manual.

My list of essential Hakuin texts

There have been many great teachers in the Zen tradition, so studying just one person (e.g., Dōgen), encourages a lopsided understanding – “a carriage only fitted out with one wheel.” Hakuin is often cited along with Dōgen as Japan’s two greatest teachers, in part because they both left extensive writings. Norman Waddell has focussed on translating Hakuin for the last decade or so and so we have quite a wonderful collection of Hakuin available now to the English reader.

Most recently, Waddell published the 743-page Complete Poison Blossoms from a Thicket of Thorn. How can a person get a toe-hold in that huge volume of work? In response to this question, I’ve focussed my list on texts that are especially good summaries of Hakuin’s teaching. Wild Ivy: The Spiritual Autobiography of Zen Master Hakuin is another essential text. Here’s my short list:

- “119. General Discourse Introductory to a Lecture Meeting on the Lotus Sutra:” Story of Hakuin’s final enlightenment and the thief kōan.

- “78. Instuctions to the Assembly at the Opening of a Lecture Meeting on the Lotus Sutra:” Probably the clearest summary of Hakuin’s teaching.

- “310. Ekyū Returned to His Home and Did Not Return for a Long Time. The Reason, I Heard, Was a Bad Cold. I Sent Him This Poem As an Angry Fist to Admonish Him:” Gives a flavor of Hakuin’s rough human feelings and his hands-on approach with this students.

- “349. Untitled [Eshō-ni]:” Addresses Eshō, a nun and close student, who had a deep realization. Introduces the “East wall strikes west wall” kōan.

- “348. Thoughts on an Old Friend:” For both Hakuin and Dōgen, the Lotus Sutra was an extraordinarily important sutra. Hakuin shares a bit about why that was in this section.

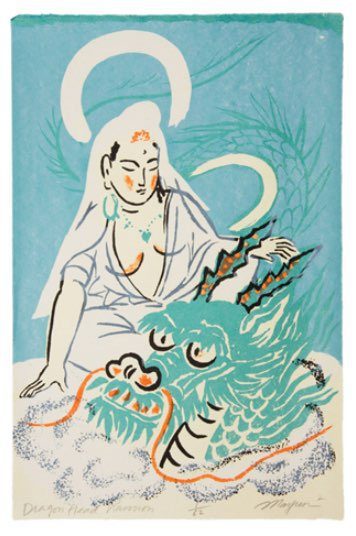

- “233. Kannon Bodhisattva, The Sixteen Arhats, and Various Devas:” Kannon bodhisattva was also a powerful inspiration for Hakuin’s verbal and visual teaching. This section also presents the “sound of one hand kōan.”

- “105. Instructions to the Assembly at the Opening of a Lecture Meeting on the Vimalakirti Sutra:” A short verse that powerfully connects kenshō with the bodhisattva heart.

- “292. Instructing Senior Priest Tetsu Who Returned for Further Study:” Another verse for a wayward student.

I’m left feeling that both of these lists are quite lacking and incomplete. But, I hope, the lists might give earnest seekers a place to start exploring their own awakened heart-mind by sampling the awakened heart-mind of these two great teachers.