And in both ways, you are being foolish, and unreasonable. Permit me to explain with the help of an article I saw this morning regarding the fact that most of us have missed the the stock market rally that turned three years old back on March 9th. I’ve got graphs and charts for your entertainment value as well.

But wait a minute, you argue. What gives you the right to analyze our actions in light of something so repellant as the device Mammon uses to weigh, grow, and destroy wealth? I mean, Frank(!), stocks and the market that deals in them are evil, man! Don’t you see that?

Nope, I don’t. Remember me? I’m the contrarian. I’m also the guy who wrote about the most successful “investing” company of all time. Oh, I’m definitely a weird one. The one who came “this close” to selling his soul to Mammon, but was called away when My Lord exercised his “call option” on my life.

That’s probably why I’m a kindred spirit with Blaise Pascal, who says,

”Since we cannot know all that is to be known of everything, we ought to know a little about everything.”

And that includes investing (especially if you have a 401k or IRA). Because the markets for stocks and bonds are no more evil than any other market, see? Because they are made up of underlying players who are no more, or less, evil than every one of us is individually. Oh, for sure, it’s “fallen” just like the whole human race, but that doesn’t make it evil. It just makes it volatile at times, placid at others, and downright scary to many who have control issues. And it is in dire need of redemption, too, because it is a reflection of all of us. It seems to many also to be like an ocean whose ebbs and flows are unknowable.

And it is all that, for sure. The wisest investors warn us that no one person is smarter than “the market.” But the ups and downs of the stock market play havoc on the minds of folks and if you aren’t aware of the landscape (seascape?) that you enter upon when you become an investor, then you will be subject to many, if not most, of the same traps and snares that have occurred, and have been uncovered, and have harmed, investors since time and markets began.

To be an investor, see, takes an act of faith. And to be a Christian takes an act of faith even greater than the faith required of an investor.

So what does all that have to do with the Church and her Bishops? I’m reminded of G.K. Chesterton’s thoughts from his essay Why I am a Catholic, is all.

There is no other case of one continuous intelligent institution that has been thinking about thinking for two thousand years. Its experience naturally covers nearly all experiences; and especially nearly all errors. The result is a map in which all the blind alleys and bad roads are clearly marked, all the ways that have been shown to be worthless by the best of all evidence: the evidence of those who have gone down them.

On this map of the mind the errors are marked as exceptions. The greater part of it consists of playgrounds and happy hunting-fields, where the mind may have as much liberty as it likes; not to mention any number of intellectual battle-fields in which the battle is indefinitely open and undecided. But it does definitely take the responsibility of marking certain roads as leading nowhere or leading to destruction, to a blank wall, or a sheer precipice. By this means, it does prevent men from wasting their time or losing their lives upon paths that have been found futile or disastrous again and again in the past, but which might otherwise entrap travelers again and again in the future. The Church does make herself responsible for warning her people against these; and upon these the real issue of the case depends. She does dogmatically defend humanity from its worst foes, those hoary and horrible and devouring monsters of the old mistakes.

And that is what the following article on behavioral finance got me to thinking about. For you doomsayers out there, you will love the title: Why Are American’s Avoiding Stocks? Ask A Shrink. So what popped into my mind? “Why Are American Catholics Avoiding the Bishops? Ask Joe Six-Pack.” But folks aren’t going to ask Joe what he thinks, so he’ll just reprint the “Stocks to Shrinks” article and comment around it accordingly.

Be patient with me and please…don’t kill the messenger. Here goes,

Why Are Americans Avoiding Stocks? Ask a Shrink

Why are Americans avoiding stocks? Experts in the field of behavior finance have a few ideas

By Matthew Craft, AP Business Writer | Associated Press – Sun, Mar 11, 2012 12:18 PM EDTThe headlines say the financial crisis is behind us. The Dow is back to pre-financial crisis levels. Layoffs are the slowest since the financial crisis, and car sales the highest since the financial crisis.

So why are Americans still too scared to get back in the stock market?

Because all they hear is “financial crisis.”

Am I really climbing out on a limb by saying that when American Catholics hear the word “Bishops” and “crisis,” they immediately associate these words with the child sex abuse scandal that has rocked the Church world-wide? I don’t think so. Visions of the “Long Lent” from 2002 come welling up immediately, don’t they? According to the combox attached to E.J. Dionne’s Washington Post article the other day, they do. Sort of like how investors became deer in the headlights in 2008,

Every comparison to 2008, even a comparison that’s supposedly good, stirs memories of 2008. For some people, it rekindles the fear of losing a job or a house. For others, years of retirement savings swallowed by a plunging stock market.

So say the experts in the budding field of behavioral finance. Professional investors and money managers may be baffled that Americans are shaking off the good news. But people with a background in psychology are hardly surprised.

What “good news?” You mean you weren’t rebalancing your 401k portfolio on March 9th, 2009, you know, at the bottom? Why not, dear reader? Afraid that for the first time ever, every company in America was going bankrupt and would disappear from the face of the earth? Heh. Back to Matthew’s article,

A broad measure of the stock market, the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, is up more than 20 percent from last October. The index has more than doubled since March 9, 2009, the low point for stocks during the Great Recession.

This calls for a photograph! The blue dot equals October of last year.

The little blue line in the chart above is the value of the Standard and Poors 500 since 1993. The red line represents the return the bond market has grown by over the same time period. But folks aren’t buying stocks now. Instead, they’re buying bonds in record numbers, you know, when they are yielding next to nothing, as noted by the Wall Street Journal,

But everyday investors refuse to jump in. They pulled $19 billion from funds that invest in U.S. stocks in December, according to the Investment Company Institute, and $2 billion more in January.

“In the old days, if there was a market rally, people would call and ask to put more money in. They felt they were missing the party,” says Deborah DeMatteo, an independent wealth manager at 10-15 Associates in Goshen, N.Y.

This time, investors seem more than happy to miss the party.

“Now, people call and ask, ‘When is it going back down?'” DeMatteo says. “There’s a sense of doom.”

What are they thinking? It’s a question fit for a shrink.

Are you still with me folks? We’re getting to the really good part! Unless, that is, you think psychology is all bunk too. Either way, prepare to look in a mirror.

Market psychology is still psychology, which is why Wall Street banks and investment firms pay people like Richard Peterson, a psychiatrist with a medical degree from the University of Texas, to help make sense of it.

A variety of emotions and thought processes are keeping Americans out of the stock market, Peterson and other experts say. The memory of 2008, when the Dow Jones industrial average swung wildly by hundreds of points a day, is probably No. 1.

The tumult of that year stamped itself in many people’s brains. Like survivors of a devastating earthquake, they carry those events with them.

“A traumatic memory gets seared in the brain,” Peterson says.

I think I can follow him here regarding the traumatic memory sear, can’t you? Think of your own experiences and I guarantee that some memory just popped into your head and you almost wanted to bolt from where you’re sitting and head for the hills, right? That’s because wounds leave scars and,

In this case, the wound is easily irritated. News that reminds people of the financial crisis — debt problems in Europe, a sudden swing in the market — sets off the same emotions of fear or anger. Getting your fear button pushed that often is exhausting, Peterson says.

People eventually tune out to save their sanity.

Golly…I wonder if folks in politics know about how psychology effects the herd? Surely they wouldn’t try to play upon our past fears, and angers, etc., in order to bend us to their will, would they? That’s just a hypothetical question from Joe Six-Pack. Please pay him no attention because,

“Fear is still with us,” says Meir Statman, a professor of finance at Santa Clara University in California and a leading expert in behavioral finance. “We live as if it’s still 2008.”

Leave it to a Jesuit-run university to have an expert in behavioral finance on the faculty. You have got to love the irony, eh? Let’s see what more the professor has to say, shall we? Eyes will be opened, that is if your mind is open. Habits drive impulses, see? And that is why we react with our gut, and not our brains, unless we realize that is silly. I mean, we don’t want to be caught dead doing what he describes next.

Statman sees a few other impulses at work. One is a habit of thinking that selects an event and uses it as the basis for understanding everything else. “We look at something and ask, ‘What is this similar to?’ Statman explains.

In good times, this leads to the folly of “return chasing” — expecting an investment, sports team or pickup line to be successful simply because it proved successful in the past.

People usually do this kind of extrapolation from recent events. But Statman suspects many are using the more distant memory of 2008 because it feels closer. “I think that what’s vivid in people’s minds is not last year but 2008,” he says.

Scars will do that to you. Time for another picture!

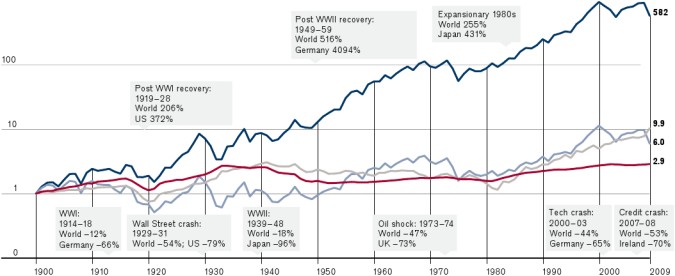

I now interrupt Matthew’s narrative for a brief history factoid provided by the evil (just kidding!) folks of Credit Suisse, who can explain the graph above.

An initial sum of USD $1 invested in US equities in 1900 grew, with dividends reinvested, at an annualized rate of 9.2% per year to become USD $14,276 by the end of 2008. Such is the power – over 109 years – of compound interest, “the mostpowerful force in the universe” (a phrase incorrectly attributed to Albert Einstein).

Since US consumer prices rose by almost 25-fold over this period (inflation, -ed.), it is more helpful to compare returns in real terms (which means “adjusted for inflation, -ed.) Figure 2 shows that an initial investment of USD $1 would have grown in purchasing power by 582 times (in stocks with dividends reinvested, -ed.).

The corresponding multiples for bonds and bills are 9.9 and 2.9 times the initial investment, respectively. These terminal real wealth figures correspond to annualized real returns of 6.0% on equities, 2.1% on bonds and 1.0% on bills.

Are you still with me, folks? See, I learned all that lingo back when I was in college and when I worked (briefly!) for Merrill Lynch. You can argue with me all day long, and fifteen hours on a Sunday why when you personally invest in stocks you have lost all your marbles, but that is kind of the point of this post, remember? Albert Einstein reportedly also said, “the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over, and over, again and expecting different results,” though I can’t prove he actually said that. Others think it was author Rita Mae Brown. No matter, because it’s a jewel that means “buying when folks are excited about an investment will guarantee you will lose.”

Meanwhile, back at Matthew’s article, we return to the fact that most folks don’t want to be confused with “the facts.”

As a result, they respond to events as if it were September 2008 and Lehman Brothers were about to collapse all over again. In this case, Statman says it’s not fear that’s driving people but an error of reasoning.

Heh! Yes, that was my bold. How about an example, more telling than the long-run chart shown above?

Last summer, for instance, a fight over raising the federal government’s debt limit led Standard & Poor’s to strip the United States of its top-flight AAA rating. The markets went wild. For the month of August, the Dow swung an average of nearly 2 percent every day.

Harvey Rowen, chief investment officer at Starmont Asset Management in San Francisco, says clients called and wanted to cash everything out. “I’d tell them, ‘You’re going to take a loss,'” he says. “And they’d say, ‘I don’t care. I want out.'”

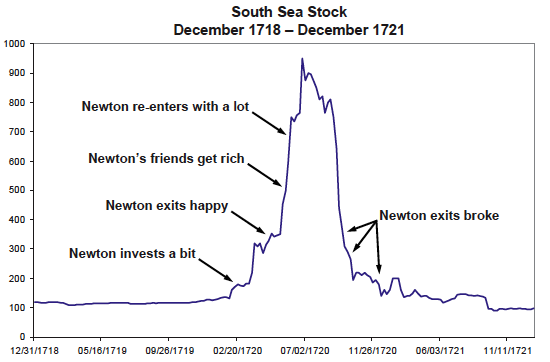

Visions of financial armageddon will do that to you. Especially if you forgot the history that warns folks to beware when markets come unhinged from the underlying economic reality that they are a proxy for. How do you know when that happens? Shall I show you Sir Issac Newton’s graphic?

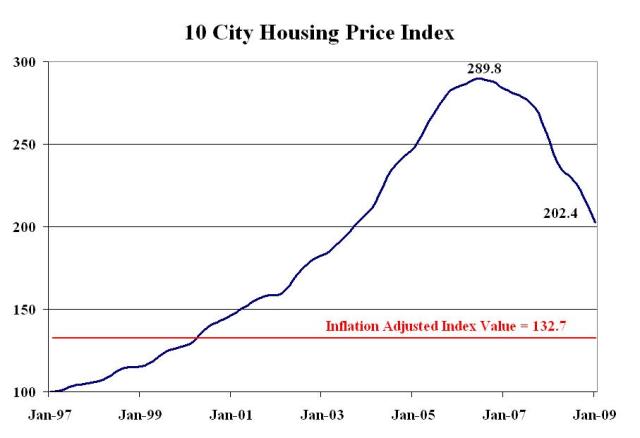

Somewhere, there is a similar graph for home prices from 1997 to 2009. Here it is, courtesy of Professor Robert Shiller.

And it’s companion graph showing how cheap housing is to buy right now, you know, when nobody wants to buy it because everyone is afraid (if they aren’t underwater).

Which leads otherwise normal folks to do what you’ll read in Matthew’s article next…

One client called with a demand to sell all his investments. He wanted Starmont to use the cash to buy gold bars, silver bars and Swiss francs and then cart them to his house. “We managed to talk him out of it,” Rowen says.

Another habit that (Professor)Statman sees at play is confirmation bias. It’s often used as a way to help explain the widening political divide in the U.S. between Democrats and Republicans.

Say you believe that the federal government’s debts will cause the U.S. to go the way of Greece. Instead of looking for information that challenges this view, you stick to news reports that confirm your opinions.

Pretty easy to do, nowadays, what with folks sticking to their favorite music, movies, news outlets, etc. New Media Cocooning, is actually confirmation bias. In that narrow world, see,

“If you have evidence that goes against your beliefs, you dismiss it,” he says.

Statman says it seems some people are looking to confirm a “doom and gloom” view of the U.S. economy. Point out that the economy grew at a 3 percent rate in the last quarter of 2011 and they’ll change the subject.

Their view, he says, is: “This country is going down the tubes.”

And that is the end of the article. By the way, “Catholic” doesn’t not mean “narrow,” saavy?

It took me an awful long time to tell you about the dangers of confirmation bias, didn’t it? By now you really shouldn’t need me to explain how many of us slip on it like a banana peel in other areas of our life. It helps explain, to me anyway, how some may underestimate the Bishops today, and how they decide to handle the HHS Mandate’s attack on our freedom, just like folks underestimated the former fishermen, the tax-collector, the zealot, the Pharisee, and the rest, who they are linked to from way back when the Church was founded by the 30 year old carpenter who died at the age of 33, and still lives today.

Stick with the Bishops, or follow the guys who say “buy high, and sell low?” Thanks for the offer, but I’ll be following my shepherds.