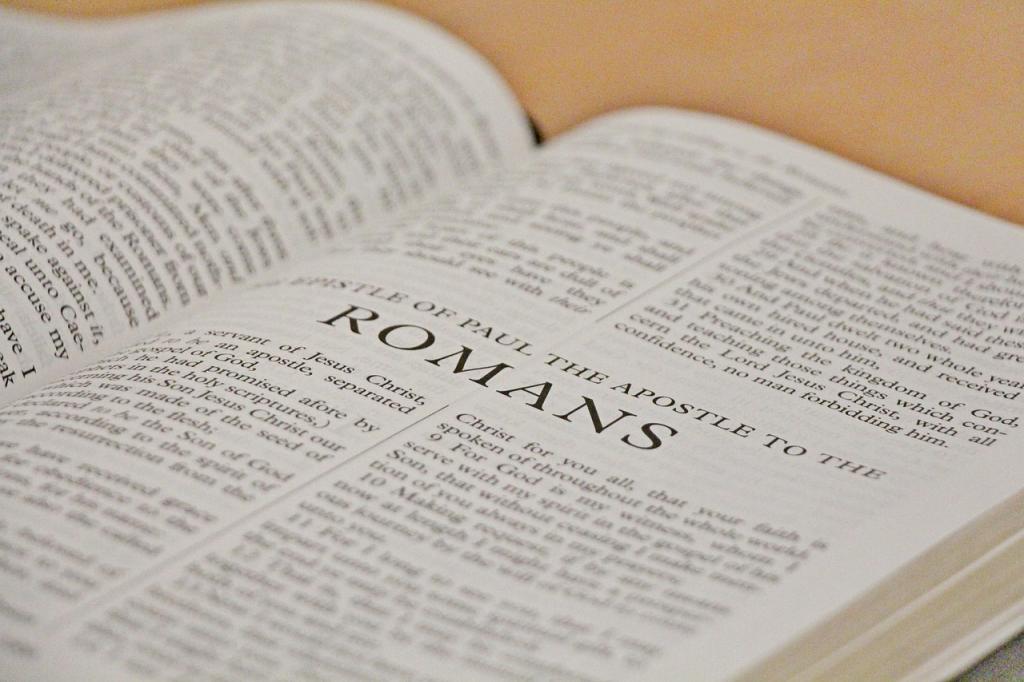

Does Romans 9 teach that God chooses individuals irrespective of their faith? Or is it that God elects based on foreknowledge of their faith? In our first instalment on the Romans 9 debate we covered ancient Jewish sects on divine determinism and freewill. We will now look at early church writers and their interpretation of Romans 9.

In Romans 9:10–23 we find God saying that he loved Jacob and hated Esau; God chose Jacob over Esau before either one could do anything good or bad. God also has mercy on whomever he wills and hardens whomever he wills. And we read that God prepares vessels of wrath for destruction and vessels of mercy for glory. How did patristic thinkers interpret this passage?

Early Christian Thinkers on Romans 9

The second century church father Irenaeus of Lyons, discussed Rebecca’s two sons (Rom 9:10–13/ Gen 25:23). When explaining that the older would server the younger, he wrote: “it is evident, that not only [were there] prophecies of the patriarchs, but also that the children brought forth by Rebecca were a prediction of the two nations; and that the one should be indeed the greater, but the other the less; that the one also should be under bondage, but the other free; but [that both should be] of one and the same father. Our God, one and the same, is also their God, who knows hidden things, who knoweth all things before they can come to pass; and for this reason has He said, ‘Jacob have I loved, but Esau have I hated.’” (Against Heresies 4.21.2).[1]

Relevant to Romans 9:14-19. Tertullian of Carthage affirmed: “God hardens the heart of Pharaoh. He deserved, however, to be influenced [apparently by Satan] to his destruction, who had already denied God, already in his pride so often rejected His ambassadors, accumulated heavy burdens on His people, and (to sum up all) as an Egyptian, had long been guilty before God of Gentile idolatry, worshipping the ibis and the crocodile in preference to the living God.” (Against Marcion, 2.14).[2]

Origen of Alexandria believed that Jacob could be determined to rule over Esau on the basis of merits related to their pre-existence, assuming they lived prior to the earthly bodies (De Principiis 2.9.7).[3]

Origen also has an interesting perspective on the divine hardening of Pharaoh in Romans 9:14–19: “the present section he [Paul] had introduced some persona that contradicts him and raises objections by saying: Is there injustice on God’s part if it is not of the one who wills or strives, but of God who shows mercy, and if [God] chose Pharaoh for the purpose of showing in him the authority of his power, and if he himself shows mercy to whom he wants and he hardens whom he wants, so that he asks, ‘Why does he still blame men and why is the one who sins found culpable, since his will would be deemed such concerning each?’[4] In other words, Paul’s opponent’s words are mostly expressed in 9:14-19, to which Paul rebukes in 9:20.

However, in another explanation about Pharaoh’s hardened heart, Origen has it that like rain, God’s kindness or miracles produce both fruits and thorns depending on human behaviors. Similarly, like the sun on wax or clay, the sun softens one and hardens the other depending on dispositions (Philocalia, 27.10; 29.9-10; cf. 21:10; De Principiis, 3.1.10–11). If so, Pharaoh’s hardened heart is not really an act of God in which he directly hardens the tyrant’s heart. Rather, by the very act of God’s supernatural plagues, Pharaoh and others experiencing them are forced to make choices, either to repent and fear God, or not. By not doing so, this in itself is what hardens them.

Ambrosiaster in his commentary on Romans, when discussing God loving Jacob and hating Esau, says, “There is no respect of persons in God’s foreknowledge. For God’s foreknowledge is that by which it is defined what the future will of each person will be, in which he will remain, by which he will either be condemned or rewarded. Some of those who will remain among the good were once evil, and some of those who will remain among the evil were once good.”[5]

On God having mercy on whomever he wills, Ambrosiaster writes, “he will call whomever he knows will obey, and he will not call whomever he knows will not obey. For to call someone is to compel him to accept the faith.”[6]

Theodoret of Cyrrhus on Romans 9:13 says, “God made the prediction by foreknowledge of their intentions. For the election was not unjust; it corresponded to their individual intentions. Paul then added a prophetic testimony, as it was written: I have loved Jacob, but I have hated Esau. God does not attend to nature but looks for virtue.”[7]

Similarly, in John Chrysostom’s Homilies on Romans, he claims that Jacob was to rule over Esau due to his worthiness of being foreknown by God. “For this was a sign of foreknowledge, that they were chosen from the very birth. That the election made according to foreknowledge, might be manifestly of God, from the first day He at once saw and proclaimed which was good and which not” (Homily 16).[8]

Regarding Rom 9:22, he states that “Pharaoh was a vessel of wrath, that is, a man who by his own hard-heartedness had kindled the wrath of God. For after enjoying much long-suffering, he became no better, but remained unimproved. Wherefore he calleth him not only ‘a vessel of wrath,’ but also one ‘fitted for destruction.’ That is, fully fitted indeed, but by his own proper self” (Homily 16 [11:468]). Translating the Greek perfect participle katērtismena with the middle voice, Chrysostom understood Pharaoh as having “fitted himself” for destruction. Had he translated this word with the passive voice, this could mean that God fitted or prepared Pharaoh for destruction. For Chrysostom, God wanted to the lead Pharaoh to repentance, bearing him with long patience, but he did not repent.

In the same homily, he explains that divine grace does not divest humans of freedom: “Because when he says, ‘it is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth,’ [Rom 9:16] he does not deprive us of free-will, but shows that all is not one’s own, for that it requires grace from above. For it is binding on us to will, and also to run: but to confide not in our own labors, but in the love of God toward man. And this he has expressed elsewhere. ‘Yet not I, but the grace which was with me.’ (1 Cor. 15:10.)” (11:469).

In Pelagius’s commentary on Romans, he writes, “Jacob and Esau too, who were born of Rebecca by a single conception, were separated in God’s sight before they were born on account of their [subsequent] faith, so that God’s purpose for choosing the good and resisting the evil existed already in his foreknowledge. So too, then, he has now chosen those whom he foreknew would believe from among the Gentiles, and has rejected those whom he foreknew would be unbelieving out of Israel.”[9] Also, regarding God’s mercy in 9:15, Pelagius claims that God foreknows who deserves mercy.

Cyril of Alexandria’s commentary on Romans goes further to suggest that even divine grace can be foreknown: “Suppose that Jacob had not turned out to be a good man or Esau an evil one, the allegation could be made that either God’s foreknowledge was erroneous or, worse, that what God ordained for each of them was based on a whim or a fickle will. Since Esau was in fact very wicked and Jacob wise, however, God’s foreknowledge would not have resulted in an unjust decision. In anticipation, God granted to the good man the love of which he would prove worthy but to the bad man the condemnation he would deserve. For God is long-suffering and awaits the proper time for things to be done when what one is becomes evident in what one does. The grace of election and the gift given on the basis of foreknowledge foreshadow the mystery that God accomplishes what is best when the time is right.”[10]

My Reflections, So Far

The viewpoint of Origen’s preexistent souls seems far-fetched to say the least. His view that an opponent’s voice took over in Rom 9:14–19 is fascinating, but perhaps more accurately we could suggest that this interlocutor raises questions in 9:14, to which Paul responds in 9:15-18. And then Paul intercepts the interlocutor’s follow-up questions in 9:19 responding to them in 9:20 and following. Nevertheless, Origen’s view on how the hardening of hearts takes place is still a viable alternative for interpreting Pharaoh’s hardening today. Likewise, John Chrysostom’s middle voice interpretation of the verb katartizo in 9:22 has it that the vessels of wrath fit themselves for destruction rather than God. This viewpoint is still supported by certain scholars today.

There appears to be a consensus with the church fathers cited above, along with others (e.g., Acacius of Caesarea, Theodore of Mopsuestia), that God could determine things in advance based on knowing beforehand human decisions and dispositions.[11] God could foresee human faith, and this is how he could choose Jacob over Esau. These ancient writers believed that an omniscient God foreknows all things and can thus elect and predestine on that basis. They also assume that Pharaoh deserves his hardening and punishment.

What we do not seem to find, at least prior to Augustine of Hippo (c. 400 CE), is a clear interpretation of Romans 9 affirming that God arbitrarily elects and predestines individuals to eternal salvation and others to eternal damnation regardless of their future faith and deeds. It is difficult for me to wrap my mind around the possibility that God did not leave a witness in the orthodox and western churches who interpreted Romans 9 along these lines. It would take Augustine, almost 350 years after Paul wrote Romans, to start reading the text in a way compatible with this.

Why such a long wait? Is the problem simply an issue of providential mystery? Or is it that these church fathers interpreted this passage from Romans 9 correctly and Augustine didn’t? We will be looking at Augustine next, so stay tuned.

Notes

[1] In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, A. Roberts, J. Donaldson, & A. C. Coxe (Eds.) (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 1:493.

[2] In The Ante-Nicene Fathers, P. Holmes (Trans.) (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Company, 1885), 3:308–309.

[3] As affirmed in the history of interpretation of Romans 9:6–29 section in William Sanday and Arthur Headlam, The Epistle to the Romans, ICC (Ediburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1902), 269–75 (269).

[4] Origen, Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans, Books 6–10 (T. P. Scheck, Trans.) (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2002).

[5] Ambrosiaster, Commentaries on Romans and 1-2 Corinthians. (Gerald L. Bray, Trans.) (Downers Grove, IL: IVP 2009), 76.

[6] Ambrosiaster, 77.

[7] J. P. Burns, C. Newman, & R. L. Wilken, R. L., eds., Romans: Interpreted by Early Christian Commentators. (J. P. Burns Jr. & C. Newman, Trans.) (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2012), 223. Quote in boldface in the original.

[8] John Chrysostom, Homilies of St. John Chrysostom, Archbishop of Constantinople, on the Epistle of St. Paul to the Romans, In Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, J. B. Morris, W. H. Simcox, & G. B. Stevens (Trans.) (New York: Christian Literature Company, 1889), 11:466.

[9] Theodore De Bruyn, ed. Pelagius’s Commentary on St. Paul’s Epistle to the Romans (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993), 116.

[10] Burns, Newman, Wilken, Romans, 227–228.

[11] See further names in John Piper, The Justification of God, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1993), 51 note 13.

Image 1: Stained glass window church via pixabay.com; Image 2: King James Version kjv via pixabay.com