“… had it not been for Gardners’ work (which in turn spawned the work of so many others), one must wonder where Neo-Paganism would be today.”

The above question was raised in the comments to my last post about the history of Neo-Paganism, specifically in reference to my statement that Wicca was “invented” by Gerald Gardner. I stand by that statement, because whether or not Gardner was initiated into anything, after he had combined it with elements of ceremonial magic, Freemasonry, and ideas from Margaret Murray’s theories, it was something new.

But my purpose here is not to debate Gerald Gardner’s bona fides. Rather, I would like to explore the question raised above: Where would Neo-Paganism be today without Wicca? I often wonder about this whenever someone begins to tell the history of Neo-Paganism with Gerald Gardner in the 1940s. For reasons that will be seen below, I think it makes more sense to date the beginning of the Neo-Pagan revival either much earlier — in the late 18th century with Thomas Taylor — or later, in 1967 — with the incorporation of Feraferia and the Church of All Worlds. While Gerald Gardner’s influence on Neo-Paganism was profound, I think there is good reason to believe that Neo-Paganism would have developed more or less along the same lines without him. In order to reach that conclusion, though, we have to take a look at what other influences led to the Neo-Pagan revival.

1. The “Pagan Temptation”

One influence which I think is often overlooked when talking about the history of Neo-Paganism is what some Christians call the “pagan temptation”. This refers to a primal or visceral drive in human beings to venerate the forces or powers of the natural world. Michael York, in his book, Pagan Theology, defines paganism as the “fundamental and atavistic human urge to express honor and homage.” He explains:

One influence which I think is often overlooked when talking about the history of Neo-Paganism is what some Christians call the “pagan temptation”. This refers to a primal or visceral drive in human beings to venerate the forces or powers of the natural world. Michael York, in his book, Pagan Theology, defines paganism as the “fundamental and atavistic human urge to express honor and homage.” He explains:

“Worship at this nonreflective and almost spontaneous stage of human growth, stripped of its theological overlay or baggage and expressive of the root level of religion, is what I am identifying as pagan.”

According to York, “pagan” behavior “is unconscious, automatic, or reflexive” and “is natural and becomes part of the consequences that spring from any fundamental human need to worship or express veneration.”

This atavistic urge seems to surge up spontaneously and unpredictably among peoples of diverse beliefs, including Christians sometimes. This often takes the form of a “revival” of a supposedly ancient pagan practice. And it is this impulse, this “pagan temptation”, which the Christian church was perpetually fighting against. One example which readers of Ronald Hutton’s work may be familiar with comes from 18th century England, where a group of Painswick gentry led an annual procession dedicated to Pan, during which a statue of the deity was held aloft. It was perhaps this same urge which led the vicar of Painswick, no less, to revive the practice in 1885, fifty years after it had died out.

There are numerous other examples of proto-Pagans who, driven perhaps by this same urge, attempted to create something like what would eventually become Neo-Paganism. One of the first of these was Thomas Taylor, who is credited with launching the Neo-Pagan movement in 19th century Britain and translated numerous works of interest to Neo-Pagans, including the Hymns of Orpheus, Apuleius’ The Golden Ass, and the writings of many Neoplatonists. (We also have Taylor to thank for the first English translations of Plato and Aristotle!) Taylor also practiced his own private reconstruction of Classical pagan religion which involved pouring libations to idols, and may have even included the rare animal sacrifice.

Other examples included Jefferson Hogg, who paid devotions to “the Religio Loci”, and his friend, the Romantic poet Shelley, who “suspended a garland, and raised a small turf-altar to the mountain-walking Pan” in the mountain behind his house. Then there was the small group of intellectuals and artists who gathered around the poet, Rupert Brooke, in the early 20th century with the intent of rebelling against Victorianism. They were dubbed the “Neo-Pagans” by Virginia Woolf. They practiced intellectual-equality for women, co-ed campouts, and bathing together. (Sound like Pagan Spirit Gathering?) And then, there was Ernest Westlake, who founded the Order of Woodcraft Chivalry, a Quaker-inspired pacifist alternative to the militaristic Baden-Powell scouting movement. According to Ronald Hutton, Westlake also sought to revive the worship of the old gods of paganism, including Pan, Dionysus, Artemis, and Aphrodite.

The perennial nature of such proto-Pagan experiments leads me to conclude that this atavistic urge, this “pagan temptation”, would have led inevitably to a Neo-Pagan revival, even in the absence of Gerald Gardner and Wicca.

2. Romantic Poetry and Transcendental Philosophy

As has been well-documented by Ronald Hutton, one of the most important influences on Neo-Paganism were the German Romantics, like Novalis, Goethe, Schiller, and Holderlin, and the British Romantics, like Percy Bysshe Shelley and Leigh Hunt, all of whom idealized the ancient pagan religions, promoted the view of nature as a living organism rather than a mechanism, and valorized heart, soul, and blood over cold, analytic reason. The Romantics emphasized the beauty and sublimity of those things which had traditionally been devalued by Christianity: woman, nature, earth, darkness, night, intoxication, the unconscious, imagination, sensation, feeling, and the passions — all values which would later be emphasized by Neo-Pagans.

Another important influence on Neo-Paganism, which is often overlooked, were the American Transcendentalists, like Emerson, Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. Interestingly, while probably speaking metaphorically, Thoreau described himself in pagan terms:

“In my Pantheon, Pan still reigns in his pristine glory, with his ruddy face, his flowing beard, and his shaggy body, his pipe and his crook, his nymph Echo, and his chosen daughter Iambe; for the great god Pan is not dead, as was rumored. No god ever dies. Perhaps of all the gods of New England and of ancient Greece, I am most constant at his shrine.”

The Transcendentalists took from the Romantics the notion that regular contact with nature was essential for recovering a human innocence that had been corrupted by civilization. They argued that the human mind and the natural world were all that was needed for genuine spiritual experience. Nature was the democratizing influence on religion, as it was seen as a source of revelation available to all — again, all ideas which would later resonate with Neo-Pagans. These ideas entered Neo-Paganism, not through Gerald Gardner, but through the Sixties Counterculture, which will be discussed below.

3. Comparative Mythology and The Neo-Pagan Mythos

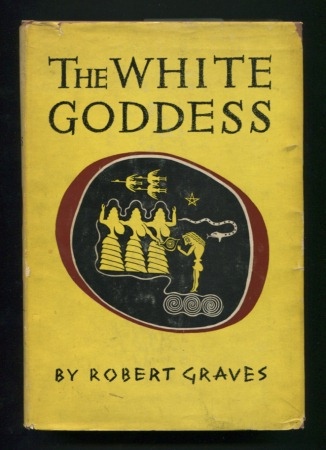

The work of comparative mythologists like James Frazer, Jane Ellen Harrison, Joseph Campbell, Mircea Eliade and — most importantly — Robert Graves, also had a profound influence on Neo-Paganism. From these scholars are derived all the elements of the Neo-Pagan Mythos, with its Dying and Reviving God and the Triple Goddess bound together by the Wheel of the Year. James Frazer, in his Golden Bough, theorized that ancient peoples believed in a dying and rising god, the animating spirit of vegetation, represented in human form as sacral kings, who are sacrificed after a term or when their power of mind or body failed, in a cyclical renewal of life. Robert Graves would develop this mythology in The White Goddess and his other works of fiction. Graves split Frazer’s Dying and Rising God into the gods of the waxing and waning year, which fight for the favor of the Triple Goddess. Graves’ conception of the seasonal interaction between these gods and the Goddess became integrated into the Neo-Pagan Wheel of the Year.

The work of comparative mythologists like James Frazer, Jane Ellen Harrison, Joseph Campbell, Mircea Eliade and — most importantly — Robert Graves, also had a profound influence on Neo-Paganism. From these scholars are derived all the elements of the Neo-Pagan Mythos, with its Dying and Reviving God and the Triple Goddess bound together by the Wheel of the Year. James Frazer, in his Golden Bough, theorized that ancient peoples believed in a dying and rising god, the animating spirit of vegetation, represented in human form as sacral kings, who are sacrificed after a term or when their power of mind or body failed, in a cyclical renewal of life. Robert Graves would develop this mythology in The White Goddess and his other works of fiction. Graves split Frazer’s Dying and Rising God into the gods of the waxing and waning year, which fight for the favor of the Triple Goddess. Graves’ conception of the seasonal interaction between these gods and the Goddess became integrated into the Neo-Pagan Wheel of the Year.

4. The Counterculture and the Environmental Movement

Fundamentally, the Neo-Pagan revival was a product of the Sixties Counterculture. According to Theodore Roszak, the Counterculture represented a challenge to the dominant cultural assumptions about the nature of humankind, society, and nature, and an attempt to effect a change in the consciousness of humankind. “The youthful disaffiliation of our time strikes beyond ideology to the level of consciousness,” wrote Roszak, “seeking to transform our deepest sense of the self, the other, and the environment.”

An important influence on the emerging Counterculture was what Alston Chase pejoratively referred to as the “California Cosmology”: the belief that everything in the universe is both sacred and interconnected, that humans in the developed world have become tragically disconnected from the cosmos as a result of the desacralization of nature, and that reconnection or resacralization is possible only through a change of consciousness. If these themes sound familiar to Pagans today, they should.

The height of the Counterculture coincided with the Neo-Pagan revival, which Sarah Pike dates to 1967, the year that Frederick Adams’ Feraferia was incorporated and the year that Oberon (then Tim) Zell filed for incorporation of the Church of All Worlds (CAW). Zell was the first to use the term “Neo-Pagan” to describe the emerging new religious movement. Although Feraferia and CAW later were influenced by Wiccan ritual forms, that happened later, well after both groups were established.

All of this also coincided with the nascent environmental movement. The year 1967 was also the year that Lynn White published “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis”, which argued that environmental decline was, at its root, a religious problem, specifically a Christian problem — an idea which was quickly adopted by many Neo-Pagans. The following year, in 1968, the Apollo 8 crew photographed the famous “Earthrise photo”, showing the living Earth rising from the horizon of the dead moon, which is credited with helping many humans realize the fragility of their home. And in 1970, the first Earth Day was celebrated and 20 million people came out for the event. The following year, Oberon Zell would have a vision which would lead him to articulate a Gaia-like theory several years before James Lovelock popularized the idea. After that, the Neo-Pagan movement began to coalesce around the idea of Neo-Paganism as an “earth religion” or “nature religion”.

5. Neo-Pagan Witchcraft and the Feminist Spirituality Movement

One of the more difficult questions in this thought experiment is: What would have become of feminist witchcraft without Gerald Gardner? The feminist spirituality movement emerged with “second-wave feminism” in the late 1960s and early 1970s, as some consciousness-raising groups developed into feminist spirituality groups. The search for uniquely feminist religious forms led many away from the monotheistic religions of Christianity and Judaism and to Wicca. According to Ronald Hutton, the integration of feminism with British witchcraft was America’s single most distinctive contribution to the development of contemporary witchcraft.

There are good reason to believe, though, that even without Wicca, there still would have been a feminist witchcraft. It seems inevitable that religious feminists still would seize on the image of the witch as an empowered woman. This connection was already made as early as 1893, by the first-wave feminist, Matilda Joslyn Gage, who also helped perpetuate the myth of the Burning Times.

In addition, Robert Graves connected medieval witchcraft to his mythos in The White Goddess, drawing on Margaret Murray’s theory. According to Graves, the “witch-cult” which had secretly survived in parts of the British Isles was just another example of the worship of his Triple Goddess. Graves even consulted with Murray for the book. So Murray’s witchcraft would have found its way to the religious feminists, even in the absence of Gerald Gardner. In fact Grevel Lindop has speculated that Gardner read the first edition of The White Goddess (1948) before he went public with his own “witch cult” (though I suspect The White Goddess was only later an influence on Wicca).

Interestingly, it was Graves, not Gerald Gardner, who feminist and author of The First Sex, Elizabeth Gould-Davis credited with inspiring the revival of the worship of the Goddess among feminists. Writing to Graves in 1973, she said:

“I suppose you know that you are the God of the new Movement here, the newest of the new women’s movements, and you are the only male creature who is admitted to godhead in the movement. It has all sorts of names because it is not yet co-ordinated. Small groups from California to New York have formed to defy Christianity and all organized religion, to worship the female principle, and to bring back the Great Goddess.”

A few years earlier, in 1969, Graves himself noted that various “White Goddess religions” had been started in New York and California: “I’m today’s hero of the love-and-flowers cult out in the Screwy State, so they tell me.”

Even if the conjunction of feminism and witchcraft had not occurred, the Goddess movement would have proceeded apace. The Goddess movement was inspired by the myth of matriarchal prehistory, which was first conceived by J. J. Bachofen in 1861, and developed by Jane Ellen Harrison, a contemporary of James Frazer. Harrison posited the existence of a “chthonic” matriarchal religion which predated the “Olympian” patriarchal cult. According to Harrison, the goddesses in matriarchal religion were husband-less, and though sometimes accompanied by a son or lover, this male figure was always subordinate to the goddess. With the coming of Olympian theology, the relationship was reversed, and the goddesses were “sequestered to servile domesticity” and became “abject and amorous”. Harrison’s ideas had a profound influence on Robert Graves, through him on Z. Budapest, and through her on Starhawk.

The myth of matriarchal prehistory was later given the appearance of archeological fact by the work of Marija Gimbutas, and further popularized by Riane Eisler and Merlin Stone. In the absence of feminist witchcraft, many women would have nevertheless found their way to the Goddess movement — as indeed happened. As Nevill Drury explains in “The Modern Magical Revival”, “Although some Goddess-worshippers continued to refer to themselves as witches, others abandoned the term altogether, preferring to regard their neopagan practice as a universal feminist religion, drawing on mythologies from many different ancient cultures.” The Goddess movement would inevitably have intersected with the Neo-Pagan Revival. In fact, today it is sometimes difficult to distinguish the two.

In summary, would there have been a Neo-Pagan revival without Wicca? Most definitely. The building blocks of the Neo-Pagan revival were already there: the ancient pagan history, the Romantic values, and the (re-)constructed mythos — all waiting for the enthusiasm and vision of the Sixties Counterculture to pull it together into the loose movement we know today.

In Part 2, I will discuss whether it is really possible to separate Wicca from Neo-Paganism and what Neo-Paganism would look like today without the influence of Wicca.