It is considerably frustrating that Mr. Warhol was an ardent, believing, and practicing Ruthenian Rite Catholic. Such an immense failure of the intellect makes him impossible to idolize in precisely the manner we wish to idolize him: As a new-age, secular artiste, champion of unexamined homosexuality and all things hip, enemy of the repressed, the medieval, and the ancient.

Now truly, Mr. Warhol was openly, undeniably gay, a laudable feat in a time less friendly to men with same-sex attraction. But to fashion the Wigged Wonder into our 21st-century, objectified caricature of a homosexual does him violence.

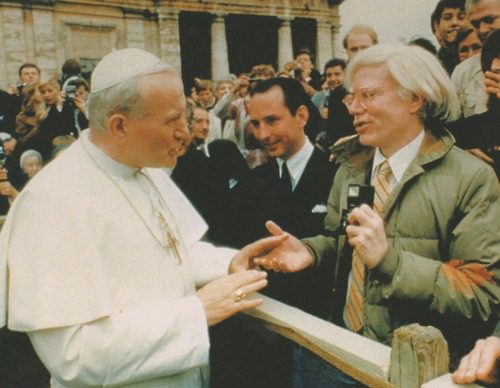

According to the wonderful book The Religious Art of Andy Warhol, by Jane Daggett Dillenberger, the man remained celibate, a  fact revealed by his own declaration of virginity and at his eulogy, where it was recalled that “as a youth he was withdrawn and reclusive, devout and celibate, and beneath the disingenuous mask that is how he at the heart remained.” He deliberately concealed who he was to the public — famously answering questions with “uh, no” or “uh, yes” — and he certainly concealed the fact that he wore a cross on a chain around his neck, carried with him a missal and a rosary, and volunteered at the soup kitchen at the Church of Heavenly Rest in New York. He went to Mass — often to daily Mass — sitting at the back, unnoticed, awkwardly embarrassed lest anyone should see he crossed himself in “the Orthodox way” — from right shoulder to left instead of left to right. He financed his nephew’s studies for the priesthood, and — according to his eulogy — was responsible for at least one person’s conversion to the Catholic faith.

fact revealed by his own declaration of virginity and at his eulogy, where it was recalled that “as a youth he was withdrawn and reclusive, devout and celibate, and beneath the disingenuous mask that is how he at the heart remained.” He deliberately concealed who he was to the public — famously answering questions with “uh, no” or “uh, yes” — and he certainly concealed the fact that he wore a cross on a chain around his neck, carried with him a missal and a rosary, and volunteered at the soup kitchen at the Church of Heavenly Rest in New York. He went to Mass — often to daily Mass — sitting at the back, unnoticed, awkwardly embarrassed lest anyone should see he crossed himself in “the Orthodox way” — from right shoulder to left instead of left to right. He financed his nephew’s studies for the priesthood, and — according to his eulogy — was responsible for at least one person’s conversion to the Catholic faith.

He painted, filmed, and photographed the obscene, the homoerotic, the trashy and the lewd, but never seriously engaged in it, saying himself that “after 25 you should look but never touch.” As the art historian John Richardson recalled: “To me Andy always seemed other worldly, almost priest-like in his ability to remain untainted by the speed freaks, leather boys, and drag queens whom he attracted…Andy was born with an innocence and humility that was impregnable–his Slavic spirituality like the Russian holy fool, the simpleton whose quasi-divine naiveté protects him against an imicable world.” While The Factory — the place he worked and a home-base for the avante-garde community — dived into debauchery late into the night, Warhol was rather infamous for leaving at 10 to go to sleep.

Whether his understanding of the amoral nature of art (by which recording and artistically expressing a sinful thing not necessarily sinful in itself) is some sort exoneration is not important. It’d be a fool who’d make him a Saint — it’s difficult to get people who flirt with cocaine on the Calendar — but it’d be the greater fool who’d make Andy Warhol a proud sinner.

For the Church Andy Warhol loves did not and does not teach that it is a sin to be gay, to carry with oneself same-sex attraction. The Catholic Church teaches that homosexual actions are detrimental to the human person, and thus sinful. For Andy Warhol to be openly gay (he mentions he’d “always had a lot of fun with that — just watching the expression on people’s faces…) and at the same time intentionally celibate seems to represent a certain peace about the man, an intellectual separation of the sinless same-sex attraction and the sinful homosexual action, and an effort at communion with the teachings of the Catholic Church. If it is sinful from the Catholic perspective, it is only sinful in that he may have lead others astray, those who did not know of his intentional celibacy.

But all this would be a view of the man, struggling for the good, failing and succeeding as only sinners can, not of the caricature our Gays vs. Hate world is comfortable with. It’s a pity, as an understanding of Warhol’s Catholicism lends a unique — and ignored — insight into his art. As Matthew J. Milliner writes for First Things on a gallery of Warhol’s art:

Massive silkscreen variations of Leonardo’s The Last Supper lined the walls, and the initial impression was that Christ had become as much fodder as Mao or Marilyn. But the negative impression didn’t last. For those with eyes to see, there emerged a message. No matter how many commercial logos one plasters over The Last Supper, no matter how the image is twisted, colored, or copied–Christ’s gesture of self-sacrificing love is tirelessly constant. For once, irony lost. It was Warhol’s final and perhaps largest series, almost certainly his finest–the resuscitation of what had become a tired visual cliche.