One of my larger worries, considering that daily question of whether to be a Catholic, is whether it means giving up the spirit of rebellion. This, after all, is the common perception of things, that the sinner is the rebel and the Saint obedient, that those who “do what they want” deserve to swagger in the feeling of self-assertion — while those who are subservient to a transcendent God have no cause for such cool.

But what is rebellion? Surely it is an assertion of self against another — but no, this would make every battle a rebellion, and every bout of Mario Party besides. It is an assertion of self against a larger force, a government or a trend or a religion, one that seeks to assimilate you into itself — but no, the family is a larger force that seeks to incorporate you into its love, as is a friendship, a fraternity, and a membership. It would be a fool who leaves his family or breaks ties with his friends and calls it a joyful rebellion, a fool who looks at a man spurning the love of his parents and admiringly applies to him an air of rugged nobility, badassery and renegade cool. Surely then, rebellion — if it can be described as a triumphant, beautiful thing — is an assertion of self in the face of a larger force that seeks to assimilate you into itself without regard for your freedom.

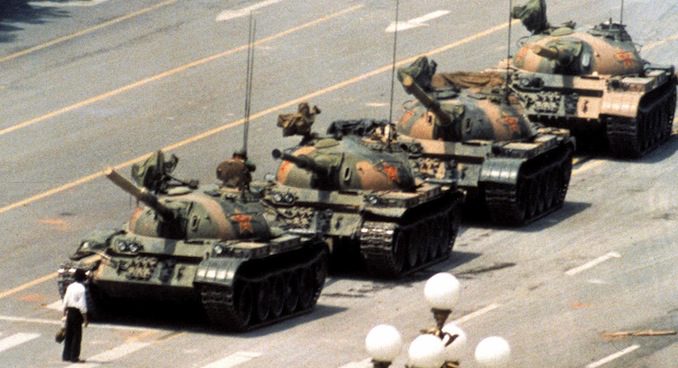

This definition fits snugly with the facts. It fits our positive feeling towards the rebel, that in his assertion of self against the looming thundercloud he posits precisely this fact — that he is free to do otherwise. Is this not the joy of the thing, the really inspiring, movie-making stuff, that no matter how large the enemy, how influential the politician, how immeasurably powerful and seducing the outside force, the smallness of man’s freedom is something larger than all the kingdoms of the earth? I may do otherwise — and this is irreducibly true. I may do otherwise, and this fact is small, but hard as a diamond. I may do otherwise, and my rebellion is to assert this incredible human power over and against every “do this” and “do that” that seeks to overwhelm me, that seeks to put the principle of my action outside of myself, so that I am swayed and moved against my freedom — by government, fashion, military compulsion, or any of the rest.

Now at a first glance, it would seem that the assertion of freedom against the demands of an Almighty God fits neatly into our category of rebellion. The Lord sayeth “Thou shall not commit adultery.” We assert the fact that we are free to do otherwise — by doing otherwise — and we walk from our supposed “sin” with the unique joy of rebellion. Jesus sayeth “woe to you rich.” We assert the fact that we are free to do otherwise — we amass wealth, we “make it big” — and walk away in the spirit of rebellion, having asserted ourselves against the assimilating power of an Almighty God.

But this rebellion is an illusion. Rebellion is the resistance of a force that seeks to assimilate you without regards to your freedom — but God regards our freedom with more care, precision and love than any parent or government could. He gives us freedom. He puts before us life and death — it is a special kind of idiocy to feel like a badass for choosing death. He gives us the freedom to choose between good and evil — is it rebellion to choose evil?

But this rebellion is an illusion. Rebellion is the resistance of a force that seeks to assimilate you without regards to your freedom — but God regards our freedom with more care, precision and love than any parent or government could. He gives us freedom. He puts before us life and death — it is a special kind of idiocy to feel like a badass for choosing death. He gives us the freedom to choose between good and evil — is it rebellion to choose evil?

If it is, it is the rebellion of a child who, invited to lunch, refuses to eat. He may wrap the thing in robes of resistance and revolution, but the fact of the matter is that his mother offered him a free choice, a choice that included the possibility of his own refusal. Choosing not to eat is not an act of rebellion, but a servile acceptance of his mother’s conditions — to eat or not to eat. It matters little whether the mother made the lunch appealing, whether she exhorted her child to eat in the strongest terms, whether she warned her child of the misery and pangs of hunger — that the mother desires her child to choose rightly in no way changes the fact that the child is free to do otherwise. So too with a God who exhorts us to do good and avoid evil.

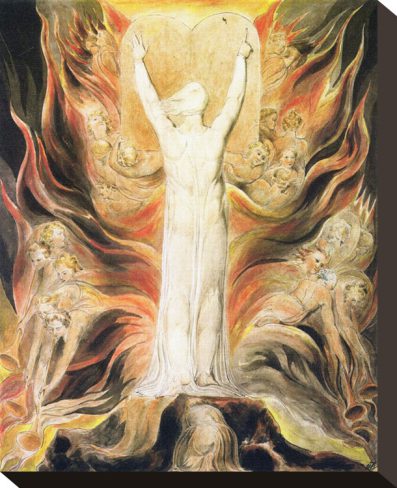

The joy that comes with an assertion of our freedom is a unique pleasure of good people, for it is not God, nor goodness, but the force of evil that seeks to assimilate us without regard to our freedom. To consistently give way to our base desires and passions is to become a slave to them, for the more often we allow ourselves to be swept away, to be tempted into doing what we ought not do, the more difficult it becomes to assert the fact that we could do otherwise. A man who welcomes every temptation towards anger and hatred does not assert himself — he acquiesces, letting anger and hatred rule over him, to the point at which he finds it impossible to do otherwise, impossible to respond to criticism with patience, to the disagreeable with love, to injustice with dignity and peace — so fixed is he in anger. A man who gives way to the force of sexual temptation does not become free, but loses his ability to say no. All sin is flirtation with addiction — but what is the experience of addiction but one of “being ruled over” by an evil, assimilating force, one that daily negates our ability to do otherwise? We give in to hatred, we bow to lust, we acquiesce to greed, to the point that we can barely sniff a temptation to these sins without running to them — and yet we call our giving in a rebellion, as if somewhere in all this weakening of our ability to do otherwise, we have proudly asserted out ability to do otherwise.

So. It is no triumphant rebellion to choose the evil that you are allowed to choose, even less so when evil negates precisely that triumph of spirit that allows you to rebel in the first place — your ability to do otherwise. Why then, does the halo of rebellion glow around the sinful, the greedy, mercilessly successful CEO, the apathetic and slothful teenager, the sexually-daring celebrity, etc.?

The joy that comes with pretending that our rejection of a God who freely offers himself to us is rebellious — this joy is an anesthetic. It is the bitter smile of the child who, having refused his mother’s invitation to lunch, comforts his growling-stomach in some lonely corner of the corner of the house by imagining himself bold, assertive, even noble in some brooding way. If we can live an illusion of rebellion, we can avoid coming to terms with the fact that we are willing slaves. If we can pretend that choosing an option we are allowed to choose somehow manifests itself as bravely resisting an authoritarian demand, we can bear the fact that in choosing to sin, we have become living contradictions, containing within ourselves what we ought not have done, an awkward, aching distance between who-we-are and who-we-ought-to-be, and a decreased capacity for free, self-determined action.

This is extremely, predictably obvious with regards to the Sexual Revolution. The Sexual Revolution must be referred to as a revolution — or else it will be revealed as a surrender. The illusion of a rebellion is a necessary anesthetic for the pain of being a slave to immediate desires, the pain of our prostration towards pornography, one-night-stands, broken families, prolonged adolescence and all the rest. Only by an illusion of the good, an illusion of that rebellious joy by which we assert our ability to do otherwise, do we find comfort from the fact that we have traded our ability to do otherwise. Only by an airy spirit of rebellion — of Revolution! — does our abject servitude become bearable.

No, if there is triumphant, joyful rebellion in this world, it is the Catholic Faith, insofar as it is an exhortation to do good, to freely choose that which most enables our ability to freely choose. Sin barks about a spirit of rebellion that the faithful quietly foster. This is the existential truth I find difficult to convey to the hardcore, that real rebellion is a quiet thing, because it is the assertion and the protection of something incredibly small, incredibly precious, and infinitely more powerful than all the princes of this age — human freedom.