The martyr is not glorified for the abuse, torture, or deprivation she suffers, as if we held her up in awe of what was taken from her. No, the martyr is something essentially positive, from the Greek martur — a witness, a pointing-towards, an icon and profound evidence of the immense value and the unspeakable worthiness of that for which she dies.

The martyr, then, is not the victim. The victim is referred to some enemy (a victim of a freak boating accident, of the measles, of terrorism) while the martyr is referred to some friend (a martyr for God, for country, for peace). The victim is referred to a moment in the past (she was a victim of gang violence) while the martyr is a martyr by virtue of a quality she has in the present moment, even after she is dead (she is a martyr). The victim is held up to direct our negative attention towards the cause of her victimhood (look at what evil has wrought!) while the martyr is held up to direct our positive attention towards the reason for her martyrdom (look at her incredible faith, her courage, her commitment, her love for God, etc.). The victim’s death works against her life, coming in the form of a homicide, a buffalo stampede, a car crash, all without any meaningful, harmonious relationship to the content of her existence. The martyr’s death, on the other hand, is in profound harmony with the content of her existence. It does not end her life, pulling down the curtain in the midst of Act II, so much as it crowns her life, a fruit and reasonable consequence of its direction and intention — she lived as a Christian and died for it.

The victim is available to being used as an emblem and symbol of the enemy, injustice or misfortune that killed her. A man might become the poster-child for an increased road tax by virtue of having been killed on an ill-funded road, despite living his life in quiet opposition to taxes of any sort, and not giving half a damn about the state of the country’s roads. But, insofar as he is considered as a victim, his life is irrelevant. It his death that matters, a death which happened to him without regard to the content of his life. Thus he may become a pure image of this misfortune — to the benefit of some political movement. The martyr, on the other hand, is a witness, and thus remains unavailable to such a postmortem re-shaping of the meaning of her existence. By giving her life away, she gives it a direction and an intention we cannot deny.

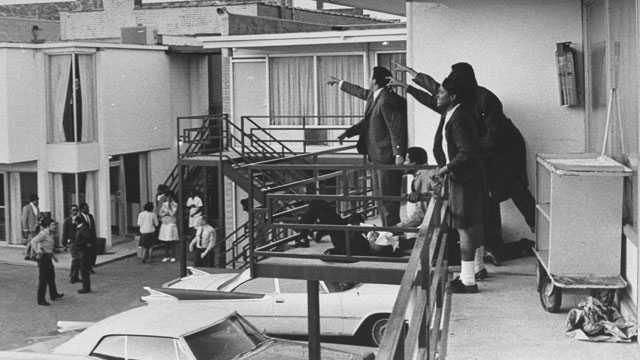

We cannot “use” the death of Dr. Martin Luther King. He died as a witness to the universal dignity and brotherhood of all men. We cannot make his death into a statement outside of the parameters he himself set for us.

We cannot “use” the death of St. Sebastian to support this political movement or that. He died as he lived, preaching Christ, and to hold him up as a means of protesting against capital punishment, say, or dictatorship, or archery — this would be odd. Sebastian does not exist in a frozen relation to his death, exhausted and swallowed up by the evil he suffered. He exists as an entire life of which death is a fruit. The martyr’s life is a proposition, a meaningful declarative sentence. He has spoken, and we do not have power over the meaning of what he has said.

If it is not clear by now, no one, under any circumstances, can be considered as a pure “victim” without undermining the fullness of their person. Certainly not from a Christian perspective — which asserts that no death is meaningless, absurd and unrelated to a person’s life — and neither from any perspective which refuses on principle to relegate a human life into a purely negative symbol of some evil, available for our use and devoid of any other identity and life.

Who would ever speak of a person this way? Bucket-loads of people. After the school shootings at Sandy Hook, partly in response to a perceived “liberal” use of the murder of innocents as an argument for gun control, “pro-life” people made this basic argument: “How can you be so concerned about the 20 children that were murdered in Sandy Hook, when over 3,000 unborn children are murdered through abortion every day?” In response to a Facebook post deploring the murder of Christians in the Holy Land, a comment was made that queer people experience just as much of a threat from the heterosexual population in America. Media outlets, in reporting the murder of the Yazidis, were “called out” by Christians for not reporting on the murder of Christians. A student I know routinely responds to claims of our culture’s sexual degradation of women with an irate response that “you should be equally concerned with our culture’s sexual degradation of men,” as many third-world feminists insist on meeting every first-world protest against unwanted sexual attention as a paltry competitor with their protest against female circumcision.

I would like to indulge the illusion that all the above examples are driven by the desire for consistency, that people rebut Christian martyrs with homosexual martyrs and shooting statistics with abortion statistics out of the desire to establish a realistic picture of the entire world of injustice. But, for however often we really do protest for a consistent ethic, it seems we usually view victims as commodities in a competitive market for power. We do combat with our dead. Denigrated into victims, the slain becomes symbols of accusation against some evil, real or perceived. Thus objectified, they may be used as threats, weapons, and knockout punches — powerful pawns of the culture wars. The person, considered as a pure victim, becomes a completely negative phenomenon, a mere reference to an enemy power, an accusation in the flesh. The person, considered as a victim, becomes evidence of evil. The glorification of the victim over the martyr is really a symptom of our generally objectified age, another form of depersonalization, one which renders a human being into a fixed object, a ‘poster-child,’ we rightly say — a mere sign of some injustice.

Sure, our Facebook posts masquerade as concern for victims, but flick the mask of solidarity and unveil an insecure and wretched tribalism — no one seems to feel grief for victims outside of his or her particular cause. And perhaps I am missing something obvious, but I find it hard to believe that there is any real concern of charity or justice for the victims used in this manner. First of all, because the person is being primarily used as a means to some end, rather than as an end in herself, but secondly, and more potently, because the obvious sense of glee with which we learn that we have a new victim on our side; the scarcely contained sense of power with which we hear that “an abortionist was murdered by a Christian,” or “a conservative was beaten up by liberals.” In these perverse times, you will rarely see a happier man than he who hears that his favorite type of person has been murdered by his least — all provided it isn’t too close to home, of course, and that he can tweet his thoughts about it in a roguish, irate, see-I-told-you-type-X-were-awful-people kind of way.

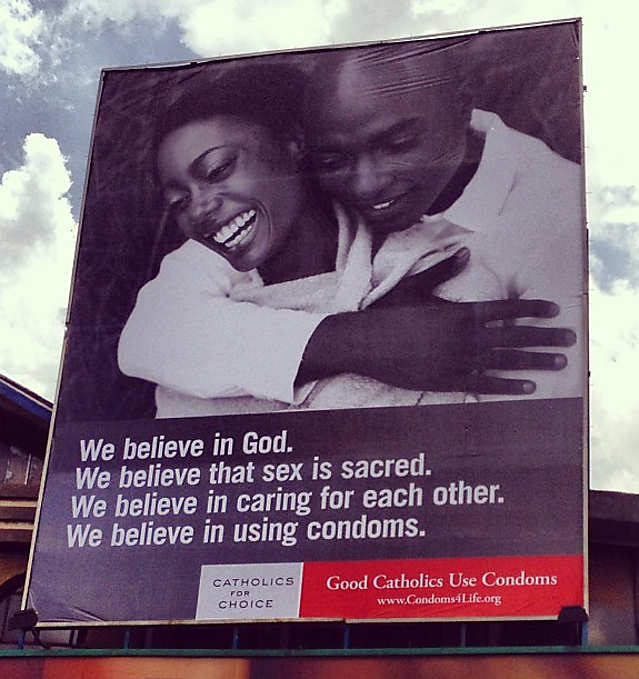

To take this view is dangerous, because it is usually directly opposed to the mode of mass media, even when it is not opposed to the message. I, for instance, am as pro-life as a newly-wed Catholic couple with real-life jobs and a copy of St. John Chrysostom’s homilies on marriage, but I cannot support the use of images of aborted fetuses as a means of pro-life protest for precisely this reason: They take an actual, particular person, freeze her into an icon of evil, and hold her up as an effective weapon, obfuscating the very point we’re trying to make — that the child in the womb is a person and not a thing. I am troubled by our treatment of those who suffer the horror of sexual assault, by the manner in which we make them ‘poster-children’ and incarnate evidences of evil, only to cast them aside when the point has been made or when their testimony does not allow us to use them as foolproof weapons against “the enemy” — even as I detest the culture of sexual assault. Such a mode undoes the very message of those standing in opposition to our society’s rape culture — that women are persons, not things. I want to praise the 21 Martyrs who would not deny Christ in face of ISIS’s prepubescent, theologically bankrupt posturing. I want to give glory to those witnesses of Christ’s love, to sing them beautiful, inspiring, heroic, holy, catholic, orthodox, illuminated, brilliant, superhuman and immortal. I do not want to use them as dead things which show how evil ISIS are. Chapter 946, then, in that awkward, embarrassing, and slow-to-surface collection: The Practical Consequences of Treating Persons as Persons.