I wrote a piece arguing against the use of “real-life stories” as something opposed to principles. In reality, our lives are lived according to principles — any moral argument that depends on narratives for its substance simply sneaks in principles through the back door. Here’s what I forgot to mention:

When personal narrative takes precedence over moral principles, the morally-justified man becomes the one with the greatest battery of relevant life-stories.

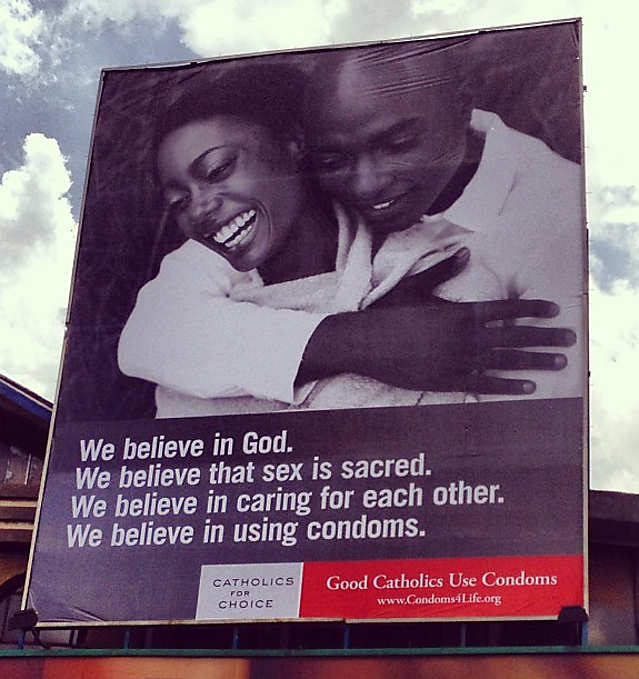

This is hardly a novel concept. By now we’ve all experienced the transformation of the gay couple into a hot commodity — the tenderhearted, liberal degradation of minority races into bullets for the Culture Wars. We shuffle and play our hand of friends like a perverse game of Pokemon: “Well I know a trans man, and let me tell you, he’s never had a problem with the bathroom setup.” “If you haven’t actually met someone who’s had an abortion, you should just shut up.” “If you don’t know a Catholic priest, you’ve got no right to criticize the institution of celibacy.”

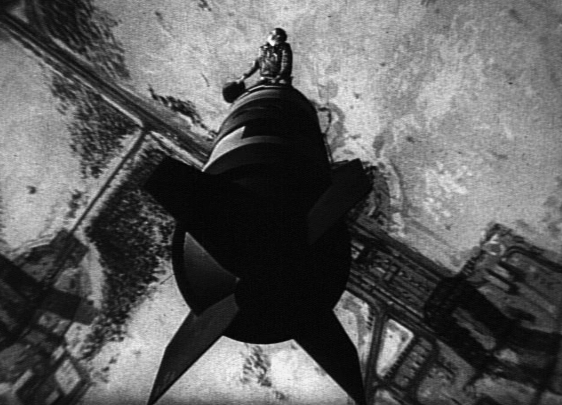

We pat ourselves on the back for this newly-developed allergy towards speaking of people as types, but treating them as trump cards is a dubious promotion. In both cases, our argument relies on the violent assumption that certain human beings cannot change. In the case of types, real people assume the characteristics of an abstract ideal — the fixed, unchanging Homeless Person, Prostitute, or Conservative. In the case of weaponized narratives, real people become grenades hurled against the half-held convictions of a wishy-washy public. Just as a grenade that loses its killing power is only fit to be cast out, so a Happy Gay Family will be dropped from the narrative arsenal the moment they become a Messed Up Gay Family. And so it goes.

The problem with narrative is that eventually we have to admit that individual narratives are judged by universal principles. This becomes obvious in the following, all-too-familiar discussion:

Person A: I have a gay friend who went through that Pray the Gay Away sh*t. It scarred him for life.

Person B: I have a same-sex attracted friend who went through genuine therapy and is now happily married to a woman. They have three kids.

Our interlocutors could realize the limits of anecdotal evidence, and begin to discuss the validity or invalidity of the universal principles by which these people understand and order their sexuality — the true or false propositions they make concerning the nature of attraction, the educability/uneducability of the passions, and so forth. In all likelihood, however, they will stay within the dogmatic bonds of narrative. They might, for instance, doubt the truth of the other’s narrative:

Person A: Well, your gay friend is probably unhappy.

Person B: Well, your gay friend is probably repressed.

But this is a limit to the powers of storytelling. You can’t argue for or against some secret underbelly that may or may not sag under an otherwise peppy narrative. One could no more bring in possible repression or probable unhappiness in a war of mutually opposed narratives then one could bring in “possible data” in an argument of medical research. Of course, it is useful to note that our suspicion that something crucial has been left out of the narrative (e.g. the tacit assumption that the no-longer-queer are hideously repressed, or the typical insinuation that happily queer aren’t really happy at all) indicates that we were operating on normative principles all along — no narrative was ever going to change our minds. Why not admit it: We instantly doubt the veracity of the narrative that goes against our basic belief that the behavior in question is a-OK or not a-OK.

But even if we do not assume this “dark side,” we might doubt the validity of the entire narrative, as in:

Person A: Do you really have any gay friends?

Person B: Do you? It seems like everyone suddenly has an intimate relationship with a Standardized, Media-Typical, Gay Man the moment it becomes convenient for them.

It’s an odd world when interlocutors make moral arguments by lying about the existence of their friends. The myth that weaponized narratives respect “the real people behind the politics” and “gives a face to the controversy” is undone by this pressure to lie — to handcraft the winning argument by making up a personal narrative. It shows that the other, far from being loved in their otherness, is being used as a tool. It shows that the human person, precisely when they are being held up as “respected,” need not exist.

Donald Trump is a master of this method. Whenever he is criticized for any principle he makes up a personal relation. When it is argued that he is being racist, he says: “Mexicans love me.” When it is argued that his views are misogynistic, he says: “I love women. I employ women.” Ready-made narratives get him out of everything. And this arrives at the point: The turn to narrative does not indicate a cultural shift towards a personalistic ethics, but a demonic shift towards an ethics of power.

Universal principles are open to everyone. They do not require a special status to be comprehended, nor a privileged position to be applied. If an act is wrong, it is wrong for everyone. If adultery is wrong on principle then it is wrong for the rich as well as the poor. The shift towards a narrative-driven public discourse undoes the democracy of the moral law and exchanges it for a moral law of the privileged. One cannot know whether abortion is right or wrong on principle; one must have the good luck, privilege, or social grace to know someone who’s had an abortion. Right and wrong is neither written on the human heart, nor available to Jew and Greek alike. It becomes a law revealed only to those purified by the right kind of personal knowledge. Ethics suffers a brutal transformation into gnosticism, and our relationships become initiations into an otherwise unavailable power — that of being morally justified. If we take this shift seriously — that one must “know person/people X before one can believe moral principle Y” — then the people of Portland must have a quantitatively better or worse insight into the moral law then the people of Savannah, simply because they are exposed to better or worse narratives. When a Miss America defends a gendered definition of marriage, it is on the basis of “being raised” to believe in it — her exposure to a certain life story justifies her belief. This is only a mask of personalism. Privilege and power rankle underneath.

If I get any donation, no matter how small, I will regard it as a challenge, and post again within the next 33 hours. Follow my Facebook page to see if someone has already challenged me to post! ![]()