In light of the unprecedented times we’re living in and the national turmoil surrounding us, I’m embarking on a semi-regular project called Movies We Need. As a believer that cinema can encourage action, restore hope and generate empathy, these are films that I believe speak to our times.

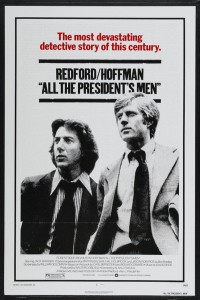

Movie: All the President’s Men (1976)

Director: Alan J. Pakula

Availability: Streaming on HBO Now/Go, available for rental on Google/ITunes, and on DVD/Blu-Ray

You guys are about to write a story that says the former Attorney General, the highest-ranking law enforcement officer in this country, is a crook! Just be sure you’re right.

So says Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee (Jason Robards) to reporters Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) in “All the President’s Men.” In one dialogue exchange, he captures the film’s focus on the power and responsibility of the press.

“All the President’s Men,” of course, is the story of how the Washington Post brought down the President of the United States. It begins with an innocuous break-in at the Watergate Hotel, a story most news outlets are happy to ignore and to which the Post assigns the two reporters. It should be noted that the paper also didn’t seem to think this was much of a story; Woodward had only been at the paper a few months and Bernstein was on the cusp of being fired. Of course, your history books tell you how this all turned out: the reporters discovered the break-in was tied to the Committee to Re-elect the President (bearing the wonderful acronym CREEP) and they revealed a conspiracy of corruption that led to Nixon’s resignation and changed American history.

Released just four years after the Watergate break-in, the film was a major hit, earning $70 million and becoming the fourth-highest-grossing movie of the year. It was nominated for several Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director; it won four, including Best Adapted Screenplay for William Goldman and Best Supporting Actor for Robards. It also contributed to Woodward and Bernstein’s legendary status. When I was in college, I lost count of how many times their names were brought up in hallowed tones by my professors (indeed, my only previous viewing of this film was in the first college journalism class I took).

and Bernstein’s legendary status. When I was in college, I lost count of how many times their names were brought up in hallowed tones by my professors (indeed, my only previous viewing of this film was in the first college journalism class I took).

The film, based on Woodward and Bernstein’s book of the same name, is exhaustively researched and doesn’t spoon feed audiences. It expects them to keep up and know their (then-recent) history as the reporters meticulously attempt to connect the dots in the conspiracy. Much of the film’s run time consists of Woodward and Bernstein talking furiously on the phone or knocking on doors to get a statement out of potential sources. Perhaps its most noteworthy shot finds them in the library, hundreds of cards of potential evidence in front of them. As they sort through them, the camera pans up further and further, dwarfing them not just by a conspiracy but by an exhausting sea of information.

Roger Ebert, who gave the film 3.5 stars, complained that the attention to detail was distracting:

The movie is as accurate about the processes used by investigative reporters as we have any right to expect, and yet process finally overwhelms narrative — we’re adrift in a sea of names, dates, telephone numbers, coincidences, lucky breaks, false leads, dogged footwork, denials, evasions, and sometimes even the truth. Just such thousands of details led up to Watergate and the Nixon resignation, yes, but the movie’s more about the details than about their results.

I disagree. With four decades of history in hindsight, we’re well aware of the results of Woodward and Bernstein’s work. The films stands as a riveting testament to the immense toil required to unseat the powerful. While I initially worried its specificity would make the film feel like a relic, the distance actually had the opposite effect. While certain names were familiar, I didn’t have to worry about being taken out of the film every five minutes because of a real-life nudge. Instead, the film feels like a thriller with a complex plot and deep mythology. The detail enriches the film, and the real-life implications don’t overwhelm it but inform it.

Power and responsibility

I probably don’t have to state that the film has a revived relevance in our current political climate. President Trump and his advisers have dubbed the press the “opposition party,” and they stand at the ready with lies and half-truths to enhance their narrative, even coining the term “alternative facts” as code for their fallacies. Now, with a president flaunting his power and a nation concerned that he won’t be kept in check, the press is more important than ever. I may be annoyed with the constant articles filling social media, but the truth is that they’re proof that journalists are hard at work. They’re doing their job, keeping the powerful in check and the populace informed. It’s tedious, sometimes boring work whose everyday drudgery hides its danger and importance.

One of the reasons “All the President’s Men” still works is because it’s a story of shoe-leather journalism filtered through the prism of a conspiracy thriller, the type of which both Pakula and Redford were known for at the time. Journalism is not a profession that is glamorous or a job that lends itself to riveting visuals. By infusing the story with the type of paranoid entertainment that fueled “Three Days of the Condor” and “The Parallax View,” the film is laced with suspense. Low-level government employees stand just outside doorways, afraid to talk. Conversations with Woodward’s secret informant Deep Throat (Hal Holbrook) take place in a dark, cavernous parking garage. There are ominous phone calls, sources who clam up at the last moment.There’s the ever-growing sense that the story is growing more vast and dangerous with every interview.

“All the President’s Men” speaks to the truth that the press can be an important, disruptive force. The movie opens with a typewriter pounding out copy. According to the film’s IMDB page, the sound of gunshots and whiplashes were mixed together with the sound of typing in this sequence. In the film’s final shot, furious typing is mixed in with the sound of a canon blast at a 21-gun salute. Words are weapons, and there’s a sense in which Woodward and Bernstein are at war with the administration. In several scenes, the reporters drive down the streets of Washington, D.C. and past the White House, which looms in the background as a reminder of all that’s at stake. The film takes this struggle to expose corruption and abuse of power seriously, providing enormous, nation-shaking stakes.

But more than just a reminder of the press’ power, it’s a reminder of the need for good journalism, something that’s also extremely relevant today. There’s good news and bad news (and also, in this day and age, “fake news”). In the shorthand of “All the President’s Men,” good news is the printed press, which takes the time to research and confirm instead of parroting soundbites and rushing for exclusives. In several moments, Woodward, Bernstein and other journalists are hard at work exposing the president’s corruption while the TV continues to blather on, its anchors seemingly uninterested in the story. On his Letterboxd page, Screencrush critic Matt Singer points out the film’s depiction of print vs. television:

The film repeatedly shows televisions, mostly around the Washington Post newsroom, presenting a counterfactual narrative of the Nixon administration that stands in complete opposition to the one assembled by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. While they search for the facts, the Post TVs mostly regurgitate the Nixon party line and publicize their “non-denial denials” of the latest Post story, propagating an illusion of a moral, lawful President unfairly attacked by a politically motivated newspaper and its agenda-driven journalists. TV obscures the truth while newspapers expose it, an idea neatly encapsulated in the final scene where Nixon is inaugurated on television in the foreground, while Woodward and Bernstein pound away on their typewriters in the background.

Not all journalism is equal, something that’s only become more true in the days of the internet. There’s a reason why Woodward and Bernstein are icons. The film celebrates their dogged pursuit of the truth, the pounding on doors, the constant phone calls, the hours in out-of-state offices. The sound of typewriters clacking pervades much of the soundtrack; shots of scribbled legal pads fill up the screen. The reporters spend late nights transcribing interviews; there’s one great moment where Redford sits at a typewriter while Hoffman pulls crumbled napkins out of his pockets. They fight for confirmation. When they get burned, they go right back to work. It’s arduous work that goes ignored and refuted for months on end, but the film’s final moments — in which we see the deluge of stories that brought down the president — show that it was necessary.

It’s also a good movie

I know it sounds like this film could be “eat your vegetables” film-going, but at 41 years old it’s still a riveting piece of entertainment. Much of that is, as I alluded to, Pakula’s knack for weaving in genre tropes to keep it engaging. But it’s also grips because it rings so deeply of truth. Pakula and his Oscar-winning cinematographer Gordon Willis were utterly committed to fidelity, going so far as to recreate the Washington Post’s newsroom and bringing in actual trash from the reporters’ desks to add to the authenticity. Redford and Hoffman, who have an engaging, easygoing rapport, shadowed journalists at the paper before filming. Robards, knowing that Bradlee never left the newsroom, even sat in his character’s on-set office with a book so he’d always be present in the background of wide shots of the newsroom. “All the President’s Men” still works because it’s a suspenseful, unbelievable tale told with skill and soaked in truth.

There was a time when Woodward, Bernstein and members of the press were respected, even revered in American culture. That’s not the case these days, when reporters occupy a social reputation just above ambulance chasers. And certainly, the crumbling financial structures of newspapers, the competition of the internet, and the rush for exclusives and ratings has led to journalism that is at times problematic, even embarrassing. And yet, as I survey our nation and I wonder how we can avoid catastrophe over the next few years, a courageous and relentless press is a key role. Americans should know the difference between good and bad news, and support quality journalism, with their clicks and with their dollars. It’s not impossible for the press to continue chipping away at an mountain of corruption and eventually bring it down. “All the President’s Men” is a reminder of that.