Our churches need more poetry.

Especially on Holy Week.

So this week, let us not be theologians or philosophers. Let us not be pastors or priests.

Let us seek to be poets.

Because on Holy Week, I’m convinced, even the world’s worst poet is better than the world’s best preacher.

But Christians, and clergy especially, can get caught up in the prose of Holy Week — the exposition and explanation, the theological and the teleological.

On social media and the blogosphere, everyone is offering their insight on what went down in Jesus’ final week. We want to offer some profound or new perspective. We want to find that fresh angle, that hot take on Holy Week.

We think it will make it more meaningful.

Part of this is a self-centeredness, a belief that Holy Week somehow depends on our contributions to it, our homilies, our blog posts, our prayers, our reflections, and our meditations. It hints at a fundamental insecurity about these stories or perhaps a quiet fear of their power to overwhelm us without the right lens to filter the pathos.

That’s why I’m grateful for the reminder that today isn’t just the Monday of Holy Week. It’s also World Poetry Day, and I hope the spirit of poets and poetry will carry us through this week.

My resolution for 2016 was to read more poetry and less the theology. Since January, I’ve immersed myself in Rainer Maria Rilke, Mary Oliver, Stephen Cushman, Billy Collins, and Alice Walker. Happily, the local clergy retreat a few weeks back, led by Bishop Porter Taylor, was backboned by meditative verse and added new poets like Naomi Shibab Nye to my cobbled syllabus. Bishop Taylor shared a series of his favorite poems and you could hear folks’ breath catching at certain arresting phrases, gentle insights, and profound images. Nye’s poem “Kindness” would well be worth sinking into this Holy Week.

“Before you know what kindness really is

you must lose things,

feel the future dissolve in a moment

like salt in a weakened broth.”

I can think of no better sentence than this to describe what happens in Holy Week.

In these few short winter months, poetry has begun to rearrange me, not because it has changed me or transformed me but because it has shown me to myself. As a lover of words and loquaciousness, of stacking dependent clauses on top of clauses like a teetering Lego tower, I’ve been humbled — and quieted — to find the marvel of a dozen words on the page that are enough to sustain me for days. Unexpectedly, I will find a poet’s phrases and images tumbling out my soul as I go about my day, like lint and coins from an open dryer.

Since January, I’ve felt the crust of dead cells that has built up around my soul like armor begin to slough off in the intentional washing of my life in the rhythms of beauty and poetry. I haven’t experienced a revelation of any sorts, but I have felt revealed, mostly to myself from whom I’ve hidden. I’ve pressed my fingertips against my exposed wounds. I’ve allowed my body to rest intensely in the pain and the joy I typically bury in the name of day-to-day efficiency. I’ve written more in my journals, things not fit for public consumption but, kept inside, would end up consuming me publicly.

I’ve begun to let go of nurtured dreams and to wonder what it be like to have the courage to dream new dreams.

I’ve been honest about my faith, and discovered that I have more than I expected, less than I understand.

Poetry has opened me up. And that’s what I think we need more of in the Christian world — more writing that opens us rather than directs us, that reveals rather than instructs, that makes us catch our breath rather than telling us how to breathe and what it means.

But as much as poetry inspires, opens, and reveals it also shouts, protests, and anguishes. It puzzles and beguiles with its neatly packaged paradoxes that unravel for days on end. Poetry is the marvel of a camel threaded through the eye of a needle stitching old gashes and opening new ones. Poetry witnesses to the best and the worst of humanity, and sees the possibility of beauty in it all. Poetry demands silence.

In other words, poetry is a lot like Holy Week.

+++

This post is brought to you by my generous patrons, Greg Strong, R.G. Lyons, John Henson, India Henson Yoga, Debra Warwick-Sabino, Randy, Roseanna Goodman, Chris Wickersham and many more. This post has its genesis in my Patrons-only newsletter. Please consider supporting my work by pledging —even just $1 — at Patreon.

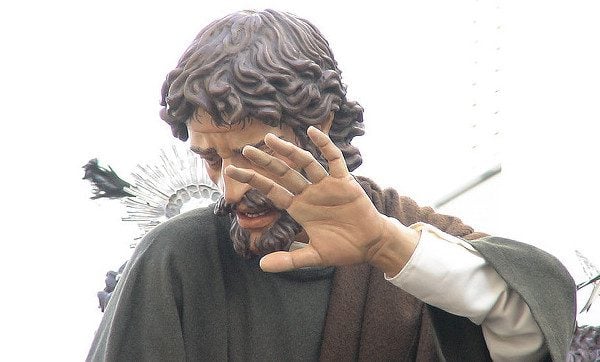

Image Credit: Albert/ Flickr, Used Under Creative Commons Copyright