It probably started at the trendy Chateau Marmont in Hollywood. Ten years ago, I sat across a movie producer who had invited me to lunch. And yet, he spent the entire lunchtime sending and receiving text messages. I didn’t understand how he could be so completely outside of his surroundings, lost in the electronic ether. Clearly, I needed to catch up with this strange new out of body experience known as texting.

Four years ago, I was struck by my students’ inability to resist the call of Facebook. They couldn’t get through a two-hour class session without updating their status and checking for new friends. Why would a mass communication professor have to banish computers and cell phones from his classroom?

Last summer, I watched my children wander around our house carrying iPads. They never turned on the television. They simply streamed whatever they wanted on Netflix, from old episodes of “Drake and Josh” to every season of “How I Met Your Mother.” The TV set had gone mobile, untethered from a particular time and place. Yet, the convenience that accompanied boundless programming also led to some addictive behaviors, far more consumption than traditional TV.

In each instance, technology was altering human behavior, pulling us into new ways of relating to our world and each other.

If a smart phone or software could change the dynamics in a friendship, a classroom, or a home, then how might technology alter our relationship with God? I began my research for iGods on a quest for a deeper understanding of where technology springs from and how people of faith and conscience should respond to new breakthroughs. I’d grown so accustomed to upgrading to new operating systems that I never bothered to question how the quest for faster and more efficient programs might be altering my values. Was I born to be an information processor? Or was I allowing a false iDol far too much prominence in my life? As a parent, I was confronted by my burgeoning teens’ request for a cell phone. Before placing a device in their hands, I needed to educate myself, to think more consciously about where technology is taking us.

What did I discover and what surprised me? For centuries, the Christian community was at the forefront of technological innovation. The mechanical clock, pews, stained glass, the organ were once new technologies. They altered our religious practices and crossed into much broader use. Yet, when I studied the current leaders in technological innovation, I didn’t see the Christian community dominating Silicon Valley. Churches may have adopted electronic instruments, projectors, and PowerPoint but they do not own the companies that create these tools.

I decided to study Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Instagram to figure out what made their contributions so valuable. Why do we view their services as so essential? What do they know about the 21st century that most of us are still slowly catching onto? I wanted to understand the creative genius of Steve Jobs, Jeff Bezos, Larry Page, and Mark Zuckerberg. What drives their decision-making and what do they think is the telos of technology? Is more access and connectivity always better? Will doing things faster or more efficiently make me a better person?

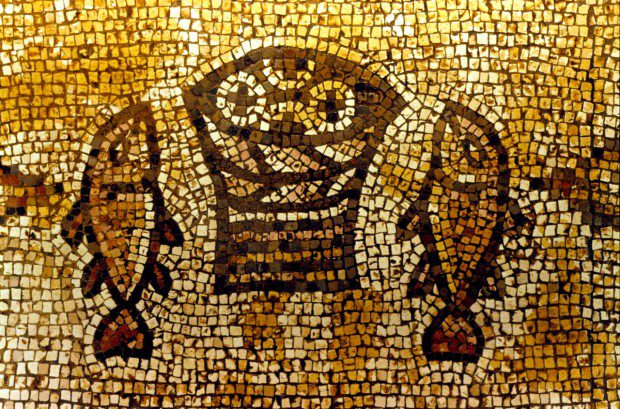

In this investigation, I hoped to develop a theology of technology that could anchor me amidst whatever upgrades competed for my attention. While we may not find computers or cell phones in the scriptures, we can see that God exerted considerable will in bringing chaotic elements under control. The primeval prologue in Genesis documents how a creative God ordered and organized the universe. When Adam and Eve’s hunger for knowledge drove them out of the Garden, God responded with clothes and tools as a consolation. Technology like an ark preserved biodiversity amidst the flood, but platform building at Babel revealed the height of human hubris. Sometimes God encourages technology; at other times, frustrates it.

As I started raising these issues with friends and colleagues, my esteemed provost at Pepperdine University told me that Jesus was more than a carpenter; he was a tekton. Could the Greek word for carpenter be translated as handyman, as architect, maybe even engineer? In our contemporary era, would we call Jesus a geek? Would we find him amidst the techies, solving problems, making others look and sound good? Maybe I needed to catch up with what God was doing in the world through technology.

I thought long and hard about what problems Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook solved. Why are they worth billions? What have they done for us to earn such unprecedented riches? They helped us deal with the new found challenge of too much—too many books, too many songs, too much information, too many relationships to keep track of. We’ve been trained to think about our economy in terms of scarcity. But the iGods got rich by helping us manage our abundance. Perhaps a theology of technology begins with a theology of abundance. I’m not advocating a prosperity Gospel that falsely suggests God helps those who help themselves, that connects wealth to God’s favor. I’m suggesting that the social media moment allows us to connect with more corners of the world than ever before, to make micro loans through kiva.com, to redistribute resources in swift and essential ways.

When Jesus was confronted with a hungry crowd, he challenged his followers to pool their resources, two fish and five loaves of bread, and give them to the throng. A miraculous multiplication followed. The leftovers demonstrated how abundantly God provides. We cannot be proprietary about God’s gifts and provisions—the kingdom is decidedly open source.