We Christians are sometimes taken to task for the way that we, when embroiled in difficult conversations about whether or not God exists, chalk things up to “mystery.” Our atheist/agnostic conversation partners see this (rightly, in some cases) as a cop out, as a way of saying, “I don’t really understand why I believe, but I do believe, so I’ll just say it’s a mystery, which will end the argument because what makes a mystery mysterious is that it remains unknown and unknowable, unexplained and inexplicable.”

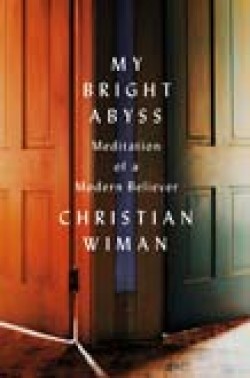

Poet Christian Wiman’s new memoir, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer tells the story of Wiman’s ambivalent embracing of Christian faith, in the context of a cancer diagnosis. The events of Wiman’s life, however, take a back seat to his contemplation of God. Using poetic language, as well as actual poems (his and others’), Wiman articulates the mysteries that abide in the heart of faith—to the extent that such mysteries can be articulated at all, which is imperfectly.

Poet Christian Wiman’s new memoir, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer tells the story of Wiman’s ambivalent embracing of Christian faith, in the context of a cancer diagnosis. The events of Wiman’s life, however, take a back seat to his contemplation of God. Using poetic language, as well as actual poems (his and others’), Wiman articulates the mysteries that abide in the heart of faith—to the extent that such mysteries can be articulated at all, which is imperfectly.

Wiman explains why a living faith requires both articulated beliefs (dogma) and a mysticism that transcends language:

[M]ystical experience needs some form of dogma in order not to dissipate into moments of spiritual intensity that are merely personal, and dogma needs regular infusions of unknowingness to keep from calcifying into the predictable, pontificating, and anti-intellectual services so common in mainstream American churches. So what does all this mean practically? It means that congregations must be conscious of the persistent and ineradicable loneliness that makes a person seek communion, with other people and with God, in the first place. It means that conservative churches that are infused with the bouncy brand of American optimism one finds in sales pitches are selling shit. It means that liberal churches that go months without mentioning the name of Jesus, much less the dying Christ, have no more spiritual purpose or significance than a local union hall.

And if we claim to understand everything about our faith, if we claim a comfortable certainty with what we believe, our faith is suspect:

There is no clean intellectual coherence, no abstract ultimate meaning to be found, and if this is not recognized, then the compulsion to find such certainty becomes its own punishment. This realization is not the end of theology, but the beginning of it: trust no theory, no religious history or creed, in which the author’s personal faith is not actively at risk.

Writing about faith feels risky to me. My shortcomings become painfully obvious. For the past week or so, an atheist commenter (going by the screen name “ngotts”) has argued with many things that I and other readers have said on the blog and in the comments. I have not responded, in part for the purely practical reason that I have been focusing my limited writing time on penning future posts as well as some work I have promised to editors. But I also haven’t responded because I have been unable to find the words with which to respond. I know the essential outlines of what I believe, but I don’t know how to explain it. I know that I see the world through a very different lens than ngotts does, but I have trouble saying why or clearly explaining how that lens alters my perceptions. I wasn’t ignoring ngotts’s questions because they were bad or silly or uninteresting. I was ignoring them because they were good questions, to which I felt unable to respond in a way that would be of value.

Sometimes I wonder what the heck I’m doing, passing myself off as a Christian writer when I don’t know how to articulate why I am a Christian.

Reading Wiman’s book has given me some new perspectives on all of this—ngotts’s (and others’) questions, my difficulty in figuring out what to say in response.

Falling back on “mystery” to explain (or not really explain) faith is not necessarily a cop out. If there really is a God who created the universe and all that is in it, including intangibles like love and beauty, isn’t some allusion to mystery necessary? If God could be entirely summed up with concrete language and tidy explanations, wouldn’t we be worshiping a tiny, limited God—one not worthy of our worship?

Only the poets among us are able to access language with which to begin to kind of sort of articulate the mysteries of God. Only poetic language can begin to articulate the mysteries abiding at faith’s core.

I am not a poet. Words will continue to elude me as I try to explain why I believe as I do. But my inability to articulate the mystical core of my faith doesn’t mean that such a core exists only in my imagination. That I am utterly unable to write a decent love poem, after all, doesn’t mean that my love for my husband is superficial and questionable. It just means I’m not a poet.

Christian Wiman is a poet—a poet with feet planted (or stuck) firmly in the muck and horror and mundanity of the world, even as he seeks something beyond it (or actually, deep within it, as Wiman argues that the reality of God is tied intimately to suffering). He writes,

If God is a salve applied to unbearable psychic wounds, or a dream figure conjured out of memory and mortal terror, or an escape from a life that has become either too appalling or too banal to bear, then I have to admit: it is not working for me.

That sort of God doesn’t work for most of us. Wiman points us to a different sort of God, one we meet in humility and suffering and art and, yes, mystery. This Bright Abyss doesn’t set out to prove anything about God, which is possibly why I found it a far more convincing defense of faith than the most thorough attempt at apologetics. “What I crave now is that integration,” Wiman writes, “some speech that is true to the transcendent nature of grace yet adequate to the hard reality, in which daily faith operates. I crave, I suppose, the poetry and the prose of knowing.” Wiman’s speech points us toward that which is unspeakable, which is probably as close to articulating the mystery of God that any of us can get.

(ngotts — I hope you’ll consider reading Wiman’s book, if only to understand why we Christian non-poets so frequently give incomplete, frustrating answers to your questions.)