Over at 9 Marks, Jonathan Leeman has an article on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood—Or Christlikeness? arguing that “It has become a common trope to argue that the Bible calls us to Christlikeness, not biblical manhood and womanhood. This is a category error. It undermines Christlikeness by turning it into something abstract, gnostic, idealized, even inhuman. It’s also antinomian.”

Hey, I like Jonathan, he’s a leading SBC ecclesiologist, just released a book One Assembly: Rethinking Multisite and Multiservice Church Models that I need to check out, but on this topic, but on this subject I think he’s turning a few partial right into an overall big wrong.

Where Leeman is right is that Christlikeness, or as I prefer to call it, the imitation of Christ, does express itself in our particular situations, whether as a female clerk in Kenya, or a male gardener in New Zealand. That itself is not a problem as discipleship always has a context and a particularity.

However, Leeman seems to be alarmed that if Christ-imitation in any way transcends gender differences or other particularities, then “Christlikeness becomes a generalized, non-specific, colorless, genderless, and frankly inhuman ideal. To use the language of the philosophers, it melts the many into the one, like a box of crayons melting into brown gray” or else it becomes “something androgynous, gnostic, anti-physical.” And herein is the problem.

I think Leeman’s concern is that if men and women can indeed imitate Christ in any sense of parity or sameness, then it potentially undermines the “rule structures he [God] has established in church and home” and that is what he’s worried about. It sounds like Christlikeness is good but only to the point that it does not interfere with a strict application of the NT household codes and a specific vision of maleness, marriage, and authority.

But note this, in the NT exhortations to follow Jesus or to imitate Jesus, they do not make gender or role distinctions, rather, the emphasis falls on what is expected of everyone!

“For I have set you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you. Very truly, I tell you, servants1 are not greater than their master, nor are messengers greater than the one who sent them. If you know these things, you are blessed if you do them” (John 13:15-17).

“I appeal to you, then, be imitators of me. For this reason I sent1 you Timothy, who is my beloved and faithful child in the Lord, to remind you of my ways in Christ Jesus, as I teach them everywhere in every church” (1 Cor 4:16-17).

“Be imitators of me, as I am of Christ” (1 Cor 11:1).

“Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children, and live in love, as Christ loved us1 and gave himself up for us, a fragrant offering and sacrifice to God” (Eph 5:1-2).

“Brothers and sisters, join in imitating me, and observe those who live according to the example you have in us” (Phil 3:17 ).

“And you became imitators of us and of the Lord, for in spite of persecution you received the word with joy inspired by the Holy Spirit, so that you became an example to all the believers in Macedonia and in Achaia” (1 Thess 1:6-7).

“And we want each one of you to show the same diligence so as to realize the full assurance of hope to the very end, so that you may not become sluggish, but imitators of those who through faith and patience inherit the promises” (Heb 6:11-12).

Furthermore, neither Jesus nor Paul, when they make their exhortations to imitation, show any worry or allergy about breaking rules, structures, or hierarchies. They are not worried about androgyny or anarchy. They do not issue caveats that the imitation of Christ comes in pink and blue. These are examples and commands for everyone, even if their expression might be different, nonetheless, they are generic and show that certain patterns of discipleship transcend differences of age, gender, ethnicity, and ableness.

This does erase not our various sub-identities of being, say, a black, female, daughter, wife, sister, aunt, mother, doctor, basketball coach, blogger; but there are holy habits, virtues, and character traits that Christ-believers share irrespective of their biological and social distinctions. There is something of Christ in all authentic Christ-followers that is recognizable, repeatable, enduring, imitative, and transcends differences, that’s surely one of the big points about being a Christian.

In other words, it is okay for men to have female role models! It means white suburban pastors can learn something about pastoring from black inner-city pastors. Soccer momes can have commonalities in discipleship with CEO’s called “Chuck.” The particularities of our selves are relative to the sameness of our shared mission, the similarities of the human experience, and the commonalities of our sanctification.

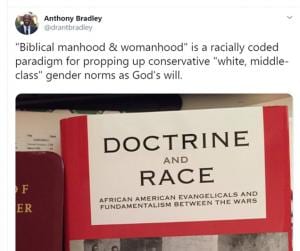

But if you want to talk about something artificial and alien to the Christian world, I would suggest it is “biblical manhood and womanhood,” which is best described in the words of Anthony Bradley:

I know it does not represent all complementarians, but it helps to remember that some of the celebrated leaders from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood brought you those classic hits like, “Women can’t be president or police officers” and “Consider hiring a housekeeper so you can have more time to work on your marriage.” So even if you swing on the complementarian side of the fence, anything badged by “Biblical Manhood and Womanhood” needs some serious discernment.

In sum, yeah, of course there is a particularity in our discipleship, but there is a way of life in Christ that transcends culture and biology, and it is precisely union with Christ and the imitation of Christ that brings us together in our differences so we can learn from each other and support each other. I like to think that such a sentiment should be agreeable to complementarians and egalitarians.

Otherwise, read Jason Hood’s awesome book on The Imitation of God and Amy Byrd’s blow-your-mind volume Recovering from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

UPDATE!

Jonathan Leeman has made a response which I’m happy to post below:

Hey brother. I genuinely appreciate you and your push back. Happy to have it. Nonetheless, I thought you would want to know if you have said things about me that are just not true. You write: “Leeman seems to be alarmed that if Christ-imitation in any way transcends gender differences or other particularities.” I don’t believe that. Christ-imitations transcends gender differences. I never say otherwise. You write: “I think Leeman’s concern is that if men and women can indeed imitate Christ in any sense of parity or sameness, then it potentially undermines the “rule structures he [God] has established in church and home” and that is what he’s worried about.” Again, not true. As I said to you on twitter, there’s much parity and sameness. You write: “They do not issue caveats that the imitation of Christ comes in pink and blue.” I don’t think they do either.

You write: “These are examples and commands for everyone, even if their expression might be different, nonetheless, they are generic and show that certain patterns of discipleship transcend differences of age, gender, ethnicity, and ableness. There is something of Christ in all authentic Christ-followers that is recognizable, repeatable, enduring, imitative, and transcends differences, that’s surely one of the big points about being a Christian.” I agree entirely, yet the implication is that I don’t.

You write: “In other words, it is okay for men to have female role models! It means white suburban pastors can learn something about pastoring from black inner-city pastors. Soccer momes can have commonalities in discipleship with CEO’s called “Chuck.” The particularities of our selves are relative to the sameness of our shared mission, the similarities of the human experience, and the commonalities of our sanctification.”

Brother, I one hundred percent affirm all this, and your clear implication is that I don’t. In fact, it’s precisely the diversity of our faith experiences that enriches and teaches all of us. Think of Bonhoeffer attending a Black church in New York, and being equipped by that for what was to follow in Germany. Likewise, here’s something I wrote in my book Rule of Love: “Biblical love, on the other hand, requires us to move out from ourselves. To draw toward someone different yet complementary. To forget ourselves temporarily and then discover ourselves more deeply. For instance, I am not a woman and I will never fully understand how it feels to be a woman. Yet God requires me to try by telling me to live with my wife in an understanding way. And so my mind must reach, stretch, lean forward in the attempt. I’m forced out of myself, my natural narcissism left behind. This might require self-denial in the beginning, which always looks painful beforehand, but ultimately I acquire a larger identity and a bigger world.”

You write: “I know it does not represent all complementarians, but it helps to remember that some of the celebrated leaders from Biblical Manhood and Womanhood brought you those classic hits like, “Women can’t be president or police officers” and “Consider hiring a housekeeper so you can have more time to work on your marriage.”Correct, this doesn’t represent all complementarians, including me. It’s occurred to me in this conversation that a number of people, when they hear “biblical manhood and womanhood,” think of Piper or Grudem’s definitions of it. That’s unfortunate because, as I’ve said in a couple of places, those brothers merely started a conversation that needs further development. What I use the phrase, I’m not referring to any one definition, I’m speaking categorically, as in “attempting to ask the Bible what it has to teach us on being a man or a woman”–doing as the Bereans did, you might say.

You write: “In sum, yeah, of course there is a particularity in our discipleship, but there is a way of life in Christ that transcends culture and biology, and it is precisely union with Christ and the imitation of Christ that brings us together in our differences so we can learn from each other and support each other.” Again, I affirm this entirely. Here’s what I say: “Christlikeness looks different in different domains… In each of these locations, Christlikeness assumes a certain shape… So, yes, our goal should always be Christlikeness. The harder question is always, “How does Christ mean for me to live here, in this domain, with these responsibilities, roles, resources, and assignments?”” You’re wanting to emphasize the one. That’s great. In this piece I’m emphasizing the many. But that doesn’t mean I deny the one. It just means that, in this particular piece, I’m emphasizing the many. In another piece I might emphasize the one, too. Bottom line: either I failed to write clearly (I’m sure I could have done a better job), or you’re taking things out of my article I never intended to put there. Bottom line: feel free to ignore this entirely. I’m simply letting you know that your piece communicates things about what I think that I don’t think. And I leave that with you.