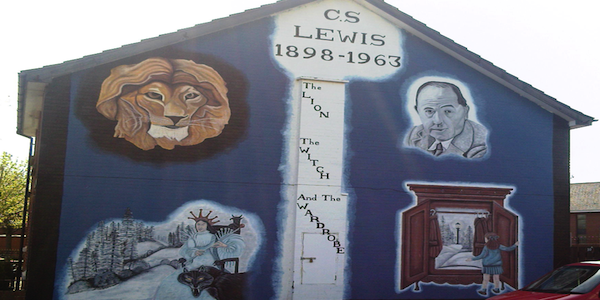

T.M. Luhrmann is a Stanford anthropologist famous for her research on evangelical devotional life, studying the mechanics of God’s presence in their lives. A few days ago, in a NY Times article, she asked and answered the following question: “Why is C.S. still a rock star for evangelicals?” In her view, it boils down to his fiction, particularly his Narnia series, which paints a complex picture of God that is “insulated from human doubt about religion.” The series, she argues, “helps us to learn what we find emotionally true in the face of irreconcilable contradictions.” This is the role of not just of C.S. Lewis’s allegorical fiction but of fiction in general, she concludes.

Many Christians would agree with her thesis about the emotional resonance of Christianity. Unapologetic: Why Christianity Makes Emotional Sense, is a book published this year by Francis Spufford, a writer and a Christian. I have not gotten a chance to read it yet, but many reviews hail it as a “new kind of apologetic” that defends Christianity not on rational grounds but on emotional, intuitive ones. Spufford writes in the legacy of Orthodoxy, a classic in Christian nonfiction, in which G.K. Chesterton details how he became convinced, on a guttural, visceral level, that the world and life had to be a certain way, and how Christianity fit his criteria—and challenged it at the same time.

Therein lies the question for Ms. Luhrmann: What happens when Christianity does not make emotional sense, but instead challenges what we find emotionally true?

If the Good Book was to be treated like fiction, we’d entertain its ideas and claims, but then ultimately set it down, taking away what we liked and discarding what we didn’t. An account of Christianity that understands it through the paradigm of fiction might explain the phenomenon of deep emotional attraction to the faith, but it does not explain the much more arduous process of discipleship in which we, certainly, gain much, but also die much and lose the selves we once were.

Ironically, in Mere Christianity C.S. Lewis himself offered a persuasive caution against understanding faith the way Luhrmann does:

I quite agree that the Christian religion is, in the long run, a thing of unspeakable comfort. But it does not begin in comfort; it begins in the dismay I have been describing, and it is of no use at all trying to go on to that comfort without first going through the dismay. In religion, as in war and everything else, comfort is the one thing you cannot get by looking for it. If you look for truth, you may find comfort in the end: if you look for comfort you will not get either comfort or truth—only soft soap and wishful thinking to begin with and, in the end, despair.

Luhrmann has been making the rounds as a sort of unusually sympathetic academic observer of religion. Sympathy she may have, but her column on Lewis shows that she has not grasped his true genius, nor the Gospel’s. It’s important not to over-rationalize the faith; it’s equally as important not to under-rationalize it.