![]() THERE IS a lot that can — and will — be said about Avatar over the next few months.

THERE IS a lot that can — and will — be said about Avatar over the next few months.

The latest sprawling epic from Titanic director James Cameron is a technical marvel and, at times, an awesome thrill ride. It also has the clunky dialogue and simplistic political and philosophical posturing that we have come to expect from his later efforts. And already there is much talk about the film’s chances at the Academy Awards in March.

For now, two points stand out for me.

First, perhaps the most interesting thing about Avatar — which is set on an alien moon called Pandora in the year 2154 — is the way it reverses some of the most famous elements in Cameron’s earlier films. In doing so, it implicates the audience in the atrocities committed by some of the human characters against the alien species there.

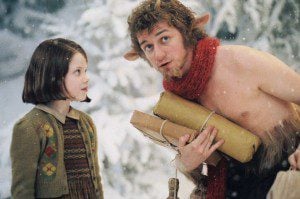

For example, Cameron’s classic sci-fi horror flick Aliens climaxed with a sort of hand-to-hand fight between a tall dark monster and a woman who evens the odds by climbing inside a machine that has arms and legs much bigger than her own.

In Avatar, there is a similar climactic battle between a large dark creature and a human-driven walking machine; but this time, the human is the bad guy — and we are supposed to be rooting for the monster.

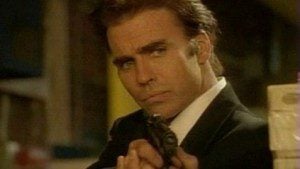

More significantly, perhaps, Terminator 2: Judgment Day revolved around a cyborg (part human, part machine) who was originally invented by other machines to infiltrate the humans against whom they were fighting — but becomes increasingly humanized, as he spends time with his former enemies.

Avatar, on the other hand, concerns a marine who projects his mind into a hybrid creature (part human, part alien) in order to spy on the aliens; and along the way, he ends up ‘going native’ and turning against his fellow humans.

The second thing to note is that Avatar is the most explicitly spiritual of Cameron’s films to date, though the spirituality on display is not without its complications.

In the past, Cameron’s films have often had an element of religious allegory or a sense of awe in the face of the unknown: consider The Terminator, which is essentially a modernized nativity story; or The Abyss, in which godlike aliens bring peace to the world.

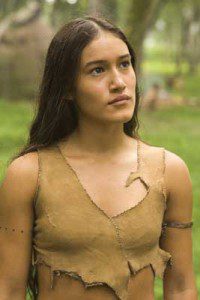

Avatar, on the other hand, puts spirituality front-and-centre in its depiction of the Na’vi, the alien race who live in harmony with nature and keep in touch with the souls of their ancestors. The aliens even worship a mother goddess whose name, Eywa, sounds a bit like Yahweh said backwards.

Humanity, on the other hand, is depicted as an utterly soulless collection of business and military interests who have already killed earth’s spirit — assuming it ever had one.

The main exception are the scientists, whose leader, the intriguingly-named Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver), wants to befriend the Na’vi and learn more about their culture.

And here’s where things get interesting: Na’vi spirituality is not simply some invisible thing that has to be taken on faith; instead, as Grace points out, it can be scientifically demonstrated because it has a biological basis.

But merely knowing about it is not enough; as the film moves along, Grace and one or two other characters come to see that subjective experience of this spirituality is more important than the objective study of it.

And while the film comes down hard against human business and human militarism, it says nothing about human religion.

So unlike a number of films that have revolved around the supposed conflict between ‘true spirituality’ and ‘organized religion,’ Avatar is content to pit postmodern faith against modern materialistic skepticism and leave it at that.

It may be rather New Age; but even so, there is something there that we can work with.

— A version of this review was first published in BC Christian News. Click here for a follow-up article on Avatar and religion that I wrote for The Anglican Planet.