Poor Rachel McAdams. She just can’t get a man to stay with her in the moment.

Poor Rachel McAdams. She just can’t get a man to stay with her in the moment.

Four years ago she was The Time Traveler’s Wife, living her life in a single linear direction while her husband lurched forwards and backwards within their relationship.

Now, in About Time, she’s married to a guy who keeps jumping back in time and making changes to her life: preventing her from meeting the man who became her boyfriend on an earlier timeline, tricking her into thinking that their second or third (and increasingly awesome) time in the sack was actually their first, fine-tuning his marriage proposal until he gets precisely the answer he wants, and so on.

At least this time she’s in a romantic comedy written and directed by Richard Curtis, who is nothing if not a crowd-pleaser. As the writer of Four Weddings and a Funeral and Notting Hill, the writer-director of Love Actually, and a scribe on countless British TV shows, he knows a thing or two about keeping the audience entertained.

So entertained, in fact, that in the case of About Time, you can almost forget the awful morality of the film’s main protagonist.

The film revolves around a man named Tim (Domhnall Gleeson, son of Brendan; he played one of the Weasley boys in the last two Harry Potter films), who at the age of 21 is told by his father (the always watchable Bill Nighy, whose cadences here got me thinking that he might be the British Christopher Walken) that the men in their family have a secret: they can travel through time, simply by going into a dark place, closing their fists, and thinking of where — or, rather, when — they’d like to go.

The mechanics of all this are not explained very well, nor are they portrayed consistently within the film.

For example, when you go back in time, do you arrive in the dark place where you began the trip (thereby making the original you vanish from wherever you were, which might come as a shock to any bystanders)? Or do you simply transfer your later consciousness to the body that you had at the time, wherever it happened to be, like the protagonist in The Butterfly Effect? Both things happen in this film, if memory serves, and there seems to be no reason for the inconsistency beyond the filmmakers doing whatever they felt was “right” dramatically in any given scene.

Also, Tim’s dad says Tim can’t go into the future, meaning the part of Tim’s life that Tim has not lived through yet, but apparently Tim can come back to the present after going to the past — even when the present is radically different because of Tim’s actions in the past. So that’s still sort of like traveling to the future, yes? I mean, he’s basically created a new timeline and jumped into the future of that timeline, right?

And if Tim is jumping from the past to the radically altered present, how does he live his new life on the timeline between those two points? He doesn’t appear to have lived it on autopilot, like Adam Sandler did when he fast-forwarded through his life in Click, but he doesn’t remember having any of the new experiences — or making any of the new choices — that he had or made on the new timeline, either.

Later in the film, we learn that Tim can take people back in time with him, too — and that he can restore the past after he’s made some unintentionally drastic changes to it. So why doesn’t he do either of these things more often?

And so on, and so on.

You might think that having a power like time-travel would have massive, even global, repercussions — but Curtis keeps things fairly small-scale. He establishes right off the bat that Tim’s family is fairly well-off, thanks to one of Tim’s ancestors, and that they keep to themselves pretty much, though they do have friends ’round for visits.

So instead of finding himself caught up in a worldwide conspiracy, like the protagonist who could teleport himself all over the globe in Jumper, Tim is free to focus on what any slightly awkward guy in his early 20s would focus on: getting a girlfriend.

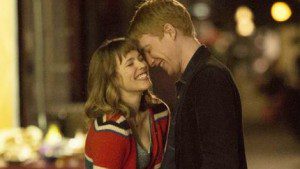

It’s certainly amusing to see Tim use his power, like Bill Murray in Groundhog Day, to learn what sort of pick-up lines would work on a girl, and then go back in time and use them on her before she’s had a chance to get to know him. But the stakes aren’t particularly high in the early scenes. It’s when Tim meets Mary (McAdams) and things start to get serious that they also become somewhat morally disquieting.

And in fact, I actually had qualms with this aspect of the film from fairly early on in Tim and Mary’s relationship.

The fact that Tim steals Mary away from a party just before her future-boyfriend shows up can sort of be justified on the basis that Mary didn’t meet that boyfriend on the original timeline anyway. Tim originally met Mary when she was still available, and it was only after he went back in time to help one of his friends that Mary met the other guy, so you could always argue that Tim is just restoring things to the way they were.

But then what? The first time Tim and Mary have sex, it’s awkward and not very satisfying — as it is indeed for most people the first time they have sex — and Mary is actually very understanding about it. But that’s not good enough for Tim, so he goes back in time and has sex with Mary for the “first” time all over again.

Tim gets the benefit of memory and experience with Mary, but Mary does not share equally in the relationship in that regard. She does not share Tim’s memories of mutual discovery. And you can’t help thinking that, from that point on, every time Mary turns one of their conversations back to this key moment in their lives, Tim will have to clam up or admit that he’s been lying to her this whole time.

The fact that Tim is exploiting Mary’s lack of memory regarding the early stages of their relationship is made all the more striking by the fact that, just last year in The Vow, McAdams played a woman who loses her memory in a car accident — thus requiring her husband to woo her all over again. For the husband of that film, the fact that she could not remember key moments from their life together was a deep wound that needed to be healed, not something that worked in the husband’s favour.

But the key scene for me — the scene where I really came to dislike Tim, at least for the next few scenes — comes after Tim and Mary have been living together for a while, and Tim goes out one evening and bumps into a girl that he had flirted with once.

Will Tim cheat on Mary? The possibility is presented to him, and, since he knows that he literally has more than one chance to accept the offer — simply by going back and reliving the evening — he abruptly leaves the girl hanging and dashes back home to propose to Mary. The implication seems to be that, if Mary says yes, then fine, Tim will stick with what he’s got, but if Mary says no, then, well, who’s to say how Tim might try to relive that evening (or the days leading up to that evening)?

I suppose we should be grateful that Tim’s first response isn’t to go through with the de facto adultery and then go back in time and prevent it from ever happening. But still, just the fact that he seems to be entertaining the idea and keeping it in his back pocket, as it were, undermines the scene for me. What does Tim plan to do if Mary says no to his proposal? Erase their relationship entirely? Leave her hanging?

The whole point of living a life connected to other people is that we are not the centres of our worlds. Other people — their lives and experiences — matter too. And this is a point that Tim seems utterly oblivious to for far too long.

So, I had some problems with the first half of the film. But then, after Tim and Mary get married and start having kids, things begin to get interesting, as Tim’s focus begins to shift back towards the family that he was born into.

As a life-long advocate for films about adult-brother relationships, I was struck by a subplot in which Tim tries to repair the damage that his younger sister Kit Kat (Lydia Wilson) has done to her life — only to find that he cannot fix her past without losing his own.

And I was especially struck by the affection that is shown between Tim and his dad as the film moves towards its conclusion.

In fact, calling About Time a “romantic comedy” may, in fact, be something of a misnomer: while romance and humour are there throughout the entire film, the wedding between Tim and Mary takes place somewhere in the middle, not the end. And the film thankfully eschews that romcom formula whereby the last 15 minutes are spent watching the couple break up and, inevitably, get back together.

Instead, the film matures from a mere romcom into something older and wiser, as Tim and his dad have some heart-to-hearts that end up becoming lessons for all of us in how to live, period, enjoying each moment for what it is.

Which is not to say that the father-son relationship is problem-free, either. There is, in fact, a rather striking moment where the film briefly adopts the father’s point of view and shows him going back in time and changing a small but key moment in Tim’s life. But it’s such a small change, and the father clearly does it as an expression of love for his son, that even a stickler like me has a hard time holding it against the guy.

The actors are all certainly very charming, and the film has some rather memorable moments, such as the scene where Tim and Mary meet for the very first time, in a restaurant where meals are served, in the dark, by blind waiters.

And it’s hard to dislike any film that has you humming an old Waterboys song for weeks afterwards — especially when the song hints at the yearning we all feel to make our time together last just a little bit longer.

So, the film ultimately left me in a good place, and for that I’m thankful. But if I could just go back, knowing what I know now, and make a few changes to the earlier part of the film… No, best just to leave it where it is. Right?