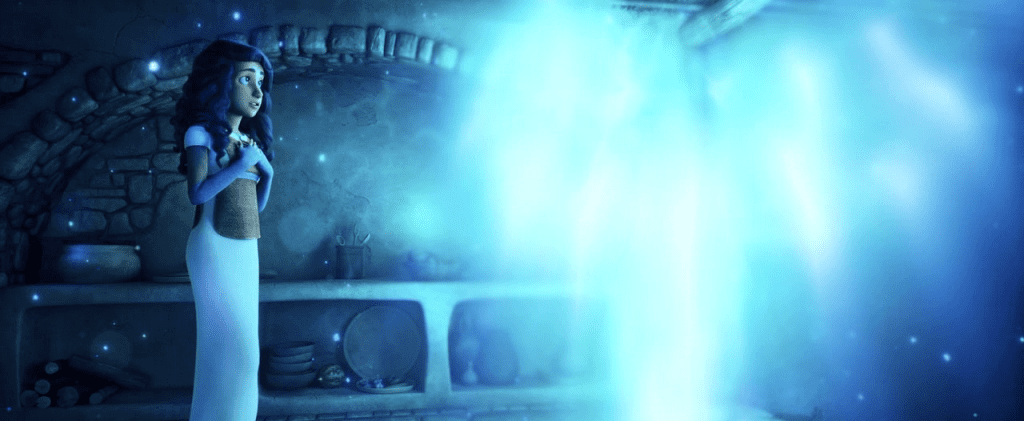

Last Saturday, I posted several new clips from The Star, including one in which an angel appears to Mary and announces that she is about to conceive the Son of God. After the angel says his piece, he turns into a ball of light and flies out her window, rising into the sky and becoming the star that draws the Magi to Bethlehem nine months later.

It’s a fascinating sequence, because it suggests that, for the movie’s purposes, the angel that appeared to Mary and the star that the Magi followed were one and the same. On one level, the film might simply have found a dramatic way to harmonize the Nativity accounts in Matthew (which tells us about the star) and Luke (which tells us about the Annunciation). But on another level, this sequence touches — however accidentally — on an ancient debate regarding the nature of the star that led the Magi to Bethlehem.

Put simply: what was the star that the Magi followed? Was it just a thing moving around in the sky? Or was it perhaps an angel or some similar conscious being?

Many people over the last few centuries have looked for naturalistic explanations for the star in Matthew’s gospel. They have argued it was something modern astronomy can comprehend: a ball of burning gas in space, or possibly a planet, or even a conjunction of stars and planets that had special symbolic significance for ancient astrologers. Interpretations along these lines have popped up in films like Franco Zeffirelli’s Jesus of Nazareth (1977) and Catherine Hardwicke’s The Nativity Story (2006), and there is an entire documentary — Frederick A. Larson’s The Star of Bethlehem (2007) — that advances the hypothesis that the star was actually the planet Jupiter.

But does modern astronomy actually explain how the star could come to rest over the specific house in which Mary and Joseph were staying (Matthew 2:9)? And would the original readers of Matthew’s gospel have thought about the star that way?

For years now, I have preferred the reading suggested by Dale C. Allison Jr. in an article that appeared in the December 1993 issue of Bible Review called ‘What Was the Star that Guided the Magi?’. Namely, he argues that the star was, itself, an angel, and that the ancient people who read Matthew’s gospel would have understood it as such.

In his article, Allison notes that the ancient Jews were just like their Greek, Zoroastrian and Egyptian contemporaries in identifying the stars as living beings, typically associated with the gods. The first-century Jewish philosopher Philo, for example, wrote that the stars “are living creatures, but of a kind composed entirely of mind” (De Plantatione), and he said God put these living creatures in the heavens just as he put aquatic creatures in the seas and land animals on the earth (De Somniis 1.135).

Allison also notes the reference to living stars in Judges 5:20 and Job 38:7, and he pairs this with the passages in Exodus (14:19, 23:23, 32:34, 33:2) that talk about angels guiding the nation of Israel in its migrations. He also points to an apocryphal source:

As support for my reading of Matthew, I can cite an old and little-studied apocryphal gospel, the so-called Arabic Gospel of the Infancy. This relates, in chapter 7, the following story:

“And it came to pass, when the Lord Jesus was born at Bethlehem of Judaea, in the time of King Herod, behold, magi came from the east. … And there were with them gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And they adored him [Jesus], and presented the gifts to him. … In the same hour there appeared to them an angel in the form of that star which had before guided them on their journey; and went away, following the guidance of its light, until they arrived in their own country.”

This, I believe, only makes explicit what is implicit in Matthew, namely, that the guiding star was a guiding angel.

Allison notes that early Christians such as Origen and St John Chrysostom seem to have believed that the stars were alive, too, but if that idea seems counterintuitive today, it could be because the early church condemned the concept at the Second Council of Constantinople in AD 553. “Thus,” says Allison, “the idea that the heavenly bodies are animate ceased to be an option for Christian theology; and with that the identification of Bethlehem’s star with an angel exited the house of exegetical options.”

Be that as it may, I think there is something to the argument that Matthew and his original readers would have understood the star to be some sort of angelic figure. And I am intrigued by the fact that The Star touches on this idea, too.